Copyright 2020 by Joe Holley

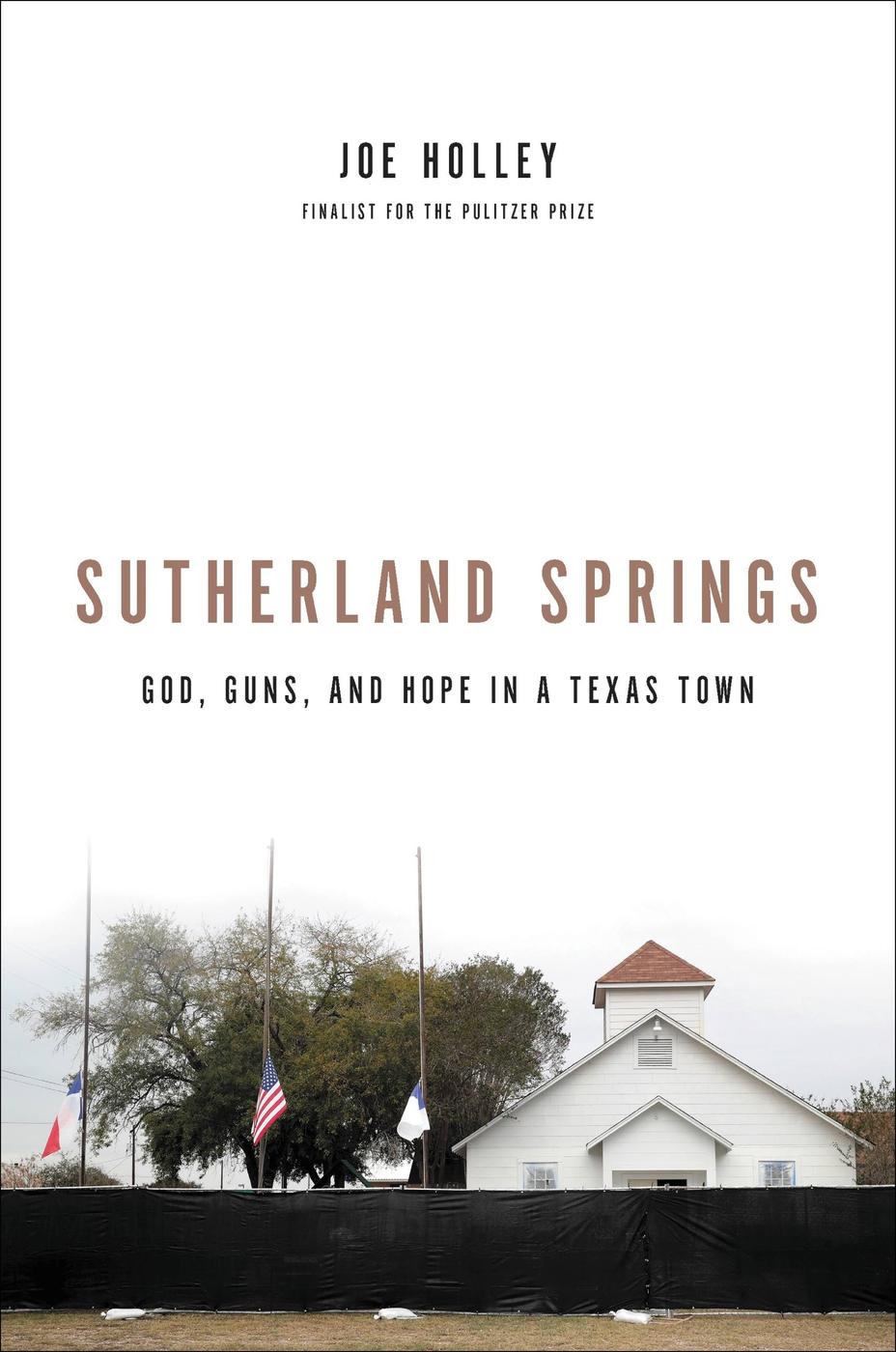

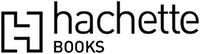

Cover design by Amanda Kain

Cover photograph Scott Olson/Getty Images

Cover copyright 2020 by Hachette Book Group, Inc.

Photographs by Lisa Krantz/San Antonio Express-News

Hachette Book Group supports the right to free expression and the value of copyright. The purpose of copyright is to encourage writers and artists to produce the creative works that enrich our culture.

The scanning, uploading, and distribution of this book without permission is a theft of the authors intellectual property. If you would like permission to use material from the book (other than for review purposes), please contact permissions@hbgusa.com. Thank you for your support of the authors rights.

Hachette Books

Hachette Book Group

1290 Avenue of the Americas

New York, NY 10104

HachetteBooks.com

Twitter.com/HachetteBooks

Instagram.com/HachetteBooks

First Edition: March 2020

Published by Hachette Books, an imprint of Perseus Books, LLC, a subsidiary of Hachette Book Group, Inc. The Hachette Books name and logo is a trademark of the Hachette Book Group.

The Hachette Speakers Bureau provides a wide range of authors for speaking events. To find out more, go to www.hachettespeakersbureau.com or call (866) 376-6591.

The publisher is not responsible for websites (or their content) that are not owned by the publisher.

Print book interior design by Sean Ford

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data has been applied for.

ISBNs: 978-0-316-45115-4 (hardcover), 978-0-316-45111-6 (ebook)

E320200131-DA-ORI

For the people of Sutherland Springs

Explore book giveaways, sneak peeks, deals, and more.

Tap here to learn more.

When peace like a river attendeth my way,

When sorrows like sea billows roll;

Whatever my lot, thou hast taught me to say,

It is well, it is well with my soul.

Hymn written by Horatio Spafford (1873)

However it happens, sometimes hearts do heal, through what I can only call grace.

Elaine Pagels, Why Religion?

Its not just our story. Its Americas story.

Holly Hannum, whose brother was killed at the First Baptist Church of Sutherland Springs

ON A FALL AFTERNOON in Austin, a Sunday, I was sitting at a table in a large, crowded tent at the Texas Book Festival signing copies of a book Id written called Hometown Texas. The book was a collection of my columns about small-town Texas that appear weekly in the Houston Chronicle. From near the tail end of the line, my daughter Kate walked up.

Did you hear about the shooting? she asked.

I had not. I wasnt sure what she was talking about, because what we have come to call mass shootings have become so depressingly familiar in this country, its hard to keep up with the most recent. This one had happened just a few hours earlier, Kate said. In Texas. She hadnt caught exactly where, although she thought it was a small town near San Antonio.

After my signing chores, I walked to my car and headed eastward toward Houston, tuning in CNN on satellite radio for the three-hour drive home. A small Texas town, I heard. A Baptist church. Multiple deaths. Sutherland Springs. It was November 5, 2017.

Despite decades of writing about Texas, including about many unlikely and overlooked people and places in my native state, I had never written about Sutherland Springs. I had written about the small Central Texas town of Hillsboro, where in the early 1930s, my Uncle JoeIm his namesakehad ended up in a jail cell with Raymond Hamilton, one of Bonnie and Clydes drivers. That Joe Holley had been incarcerated for stealing chickens to feed his family; Hamilton had robbed a jewelry store and killed the owner.

I had written about the venerable opera house in Nacogdoches, where in 1907 a musical quartet of young vaudeville performers calling themselves the Four Nightingales were upstaged by a runaway mule; that bizarre incident prompted the Nightingales (actually the Marx brothers) to realize they were comedians, not musicians.

I had written about cowboy poets in Alpine, buffalo soldiers in Fort Davis, the author of the longest novel in the English language in Waco, and a tinkerer in the picturesque German community of Fredericksburg who may have invented the airplane in the mid-1800s.

I had written about the rascally old Indian fighter/Texas Ranger Bigfoot Wallacewho called his trusty rifle Sweet Lipsand the tiny South Texas town named in his honor. Not Wallace. Bigfoot. My mother was the Bigfoot High School valedictorian, class of 1932. Most small Texas towns were replete with the three Psplace, people, and a colorful pastand I was familiar with dozens of them. Sutherland Springs was only about sixty-five miles northeast of Bigfoot, but not only had I never written about the place, I had never heard of it, had never noticed it on a map. As I would come to find out, it was easy to miss.

As I listened to increasingly grim and distressing reports as I drove, an old reporters instinct kicked in. I had to go find out. I took the I-35 toward San Antonio, eighty miles southward.

A little more than an hour later, I looped around San Antonios suburban fringe, a network of subdivisions and strip centers, and turned southeast along a two-lane blacktop through gently rolling pastureland dotted with mesquite and mottes of live oak. I passed cattle grazing, occasionally horses, fields of baled hay. Brick or stone ranch-style houses set away from the road behind wire fencing were attractive and well kept. Giant they were not. They appeared to be country getaways or maybe ranchettes, small cattle operations that retirees or refugees from the city operated. It was rural South Texas, pleasant enough but nothing spectacular, nothing out of the ordinary.

Sutherland Springs is not really a town but an unincorporated community bisected by a busy highway. Traffic ignores the blinking yellow light. Sutherland Springs has no downtown business district, no school, no noticeable landmark. (It does have a colorful history, but I didnt know that at the time.)

The sun set as I drove. Crossing narrow, tree-lined Cibolo Creek and heading up a slight incline, I passed a Sutherland Springs city limits sign. I slowed to a crawl as knots of people loomed out of the darkness. Huge satellite trucks and police vehicles, red lights flashing, crowded the highway. Rubberneckers spilled into the blinking-light intersection of state Highway 87 and Farm Road 539. A sheriffs deputy in a western hat and reflective vest directed motorists unaccustomed to slowing down.

I parked along a street of modest frame houses and ramshackle mobile homes a couple of blocks from the First Baptist Church of Sutherland Springs, the site a few hours earlier of the worst mass shooting in modern Texas history. The small, boxy building, its exterior walls clad in weathered white siding, its wooden front door positioned under a squat steeple, was bathed in harsh light brighter than a summer days. Yellow crime scene tape kept the curious out of the front yard.

In the post office parking lot across the highway from the church, a middle-aged Hispanic man wearing all black was conducting a candlelight prayer vigil. I propose that we make a pact that in this small town that evil will not prevail, he was saying as I walked up. Recorded gospel music played from a speaker on the ground nearby.

Next page