IMAGES

of America

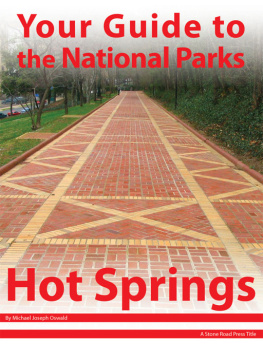

HOT SPRINGS

NATIONAL PARK

The Noble Fountain stands in front of the Superintendents Office, which spans from the reservation years to the early national park days. Constructed in 1891, this building was initially designed to contain pumps for the thermal water system, but it was never used for that purpose. It was remodeled in 1898 to house the reservation superintendents office when his workplace was moved out of his residence on Fountain Street. (Courtesy of Hot Springs National Park archives.)

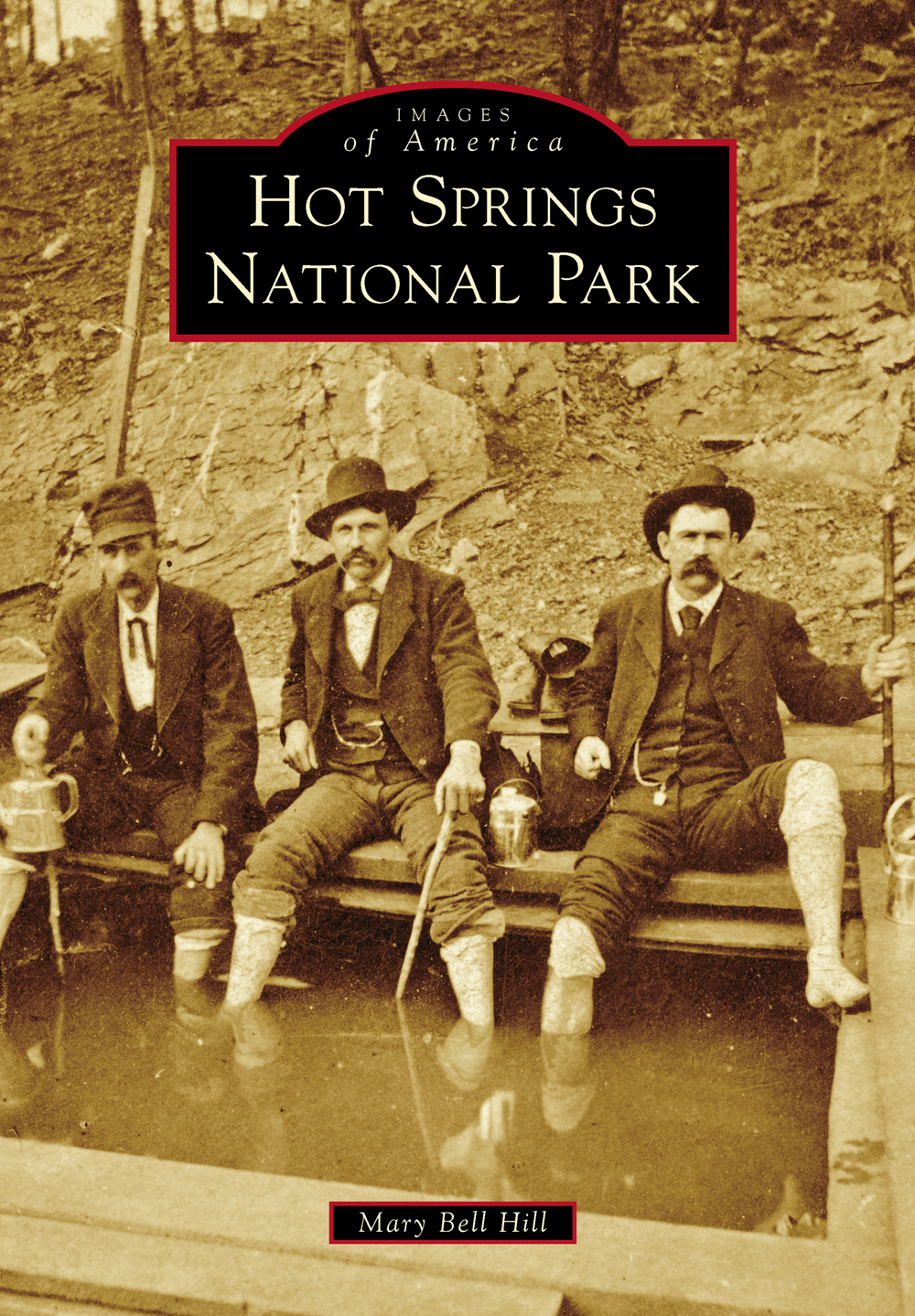

ON THE COVER: Bathers came from all over the country to partake of the thermal waters flowing from the mountains in Hot Springs. These three men are enjoying a dip in the footbath spring called the Corn Hole. Initially, conditions at the springs were rustic, but over time the facilities to take the cure became much more elaborate. (Courtesy of Hot Springs National Park archives.)

IMAGES

of America

HOT SPRINGS

NATIONAL PARK

Mary Bell Hill

Copyright 2014 by Mary Bell Hill

ISBN 978-1-4671-1285-7

Ebook ISBN 9781439648322

Published by Arcadia Publishing

Charleston, South Carolina

Library of Congress Control Number: 2014938043

For all general information, please contact Arcadia Publishing:

Telephone 843-853-2070

Fax 843-853-0044

E-mail

For customer service and orders:

Toll-Free 1-888-313-2665

Visit us on the Internet at www.arcadiapublishing.com

To my parents, Joyce and Lavan Bell, who instilled in me a love of national parks, and to my husband, Tom Hill, who shares that love.

CONTENTS

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

I would like to thank everyone who played a role in the creation of this book. Title manager Julia Simpson and publishing editor Lydia Rollins at Arcadia Publishing provided me with opportunity, inspiration, and encouragement throughout this project and helped keep me stay on track. A big thank-you goes to Hot Springs National Park superintendent Josie Fernandez for giving me access to the parks archival collection, and to chief of resource management and visitor services Mike Kusch, who took time from his busy schedule to review the manuscript. My thanks go to Liz Robbins and the staff at the Garland County Historical Society, who allowed me into their great collection of photographs and entertained me with dozens of stories about the city. I especially want to thank James O. Cary for being so kind to let me visit with him in his home in Dallas and to borrow a photograph of his father. It was an afternoon that I will not forget. Thank you also to my sports historian and great brother-in-law Mike Dugan for letting me use the photographs of his great-grandfather and providing me with information on the baseball players who made Hot Springs their second home. Thanks go to retired interpretive ranger Gail Payton Sears, who generously provided me with information on her great-grandfather and his career. My parents, Joyce and Lavan Bell, my sister Susan Bell Dugan, and my friend James Sanderson all get a huge thank-you for their proofreading, suggestions, and support that only made this project better. Most of all, I want to thank my wonderful husband, Tom Hill, the curator at the park, who answered endless questions with patience and lots of humor when I needed it.

Unless otherwise noted, photographs in this book are pulled from the Hot Springs National Park archives. Images from other sources are credited within their captions. All errors or omissions made in this manuscript are solely my responsibility.

INTRODUCTION

People have been coming to the area known today as Hot Springs National Park for thousands of years. Some came to quarry the smooth novaculite stone found in the surrounding hills, some to bathe in the soothing thermal waters pouring from Hot Springs Mountain, and, later, others to make a living off the hordes of road-weary travelers who trekked here. Many believed the hot springwater to be curative; some believed it to be mystical. All were looking for something unique in the narrow Valley of the Vapors.

This area became part of the United States with the Louisiana Purchase in 1803. The region had already been explored by French trappers and mapped by the Spanish, and it was reasonably well known to many Americans. Yet, in 1804, Pres. Thomas Jefferson dispatched an exploratory party led by William Dunbar and George Hunter to survey the Ouachita River Basin and make scientific observations along the way. The expedition spent a month camped in the Hot Springs area, reporting back that people were already visiting and using the thermal springs seasonally. No permanent white residents were to be found in the area, but that would soon change.

The small and growing settlement around the hot springs of the Washita became part of the Territory of Arkansas when it was organized in July 1819. Realizing the potential medicinal value of the thermal waters to all citizens of the young nation, the territorial legislature first petitioned Congress in 1820 to reserve the area from the public domain. This appeal was finally heeded in 1832 with the creation of Hot Springs Reservation, one of the earliest land-conservation efforts in US history.

The first rudimentary facilities erected to accommodate bathers consisted of simple shanties of rough boards surrounding dugout pools at the sites of several springs. Early lodging facilities were very basic establishments. In fact, some indigent visitors camped out on the hillsides surrounding the valley. Later, as more and more people came to town and demanded better facilities, offerings began to improve. Small hotels sprang up, and better bathing establishments began to appear.

Federal regulation of bathing establishments and business practices tightened in 1877 when the first reservation superintendent was assigned to the area by the secretary of the interior. Shantytowns were eliminated, and rigorous rules and regulations were established and disseminated. Over the years, a progression of well-appointed wooden Victorian bathhouses replaced rough board shacks at the springs. Health-seekers and casual visitors alike arrived in ever-greater numbers, while businesses and improved lodging arose to serve this rising influx. Larger and more sanitary masonry bathhouses with marble and tile interiors eventually replaced their wooden predecessors, and bathhouse owners vied with each other to offer prospective patrons the best services and amenities. Beginning in 1910, government-appointed medical directors improved control of the sanitary and hygienic conditions in the bathing institutions, including the free bathhouse operated for indigents by the federal government. The once-sleepy little hamlet in the Arkansas wilderness found itself a national destination for sufferers with a variety of ills and physical complaints.

In 1916, the National Park Service was created as an agency of the Department of the Interior and given management authority over the growing system of national parks and monuments across the country, including Hot Springs Reservation. In 1921, with the support of park service director Stephen Mather, the 89-year-old Hot Springs Reservation was re-designated by Congress as Hot Springs National Park. Soon, the nations bustling health resort was on its way to becoming the Great American Spa. Although many visitors made the trek to the waters for their ailments, others simply came for relaxing vacations with their families and friends, enjoying the natural wonders of the park.

Next page