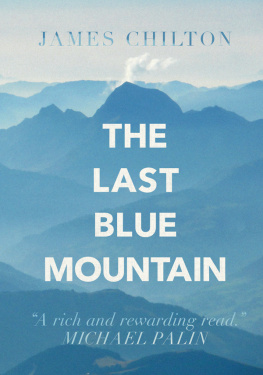

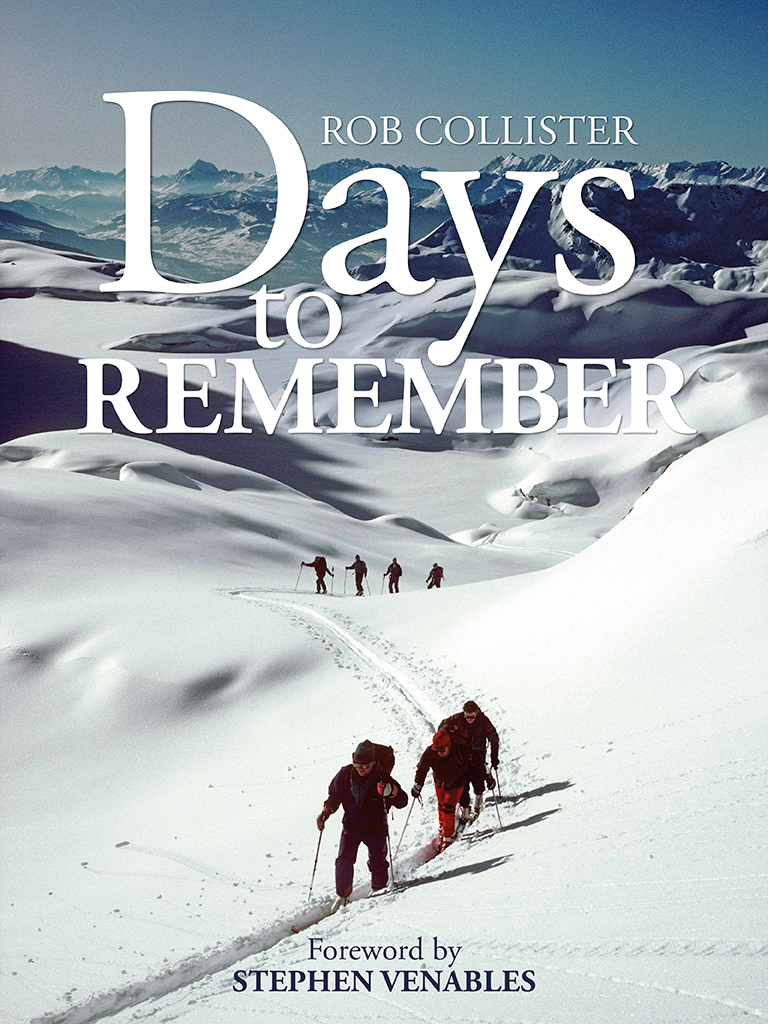

Foreword

Stephen Venables

Once upon a time, in the early 1970s, when I was young and newly intoxicated by mountaineering, but living far from the mountains, I fed my addiction by reading. I devoured the classic narratives of Eric Shipton, Gwen Moffat, Dorothy Pilley, Hermann Buhl, Lionel Terray and dozens of other mountain heroes. But for contemporary inspiration I relied on the bi-monthly magazine Mountain, whose editor, Ken Wilson, had a knack of winkling out those climbers who were doing both interesting stuff and knew how to write about it. To my mind one of the most eloquent of those mountain writers was Rob Collister.

Here was a man who seemed to achieve all the things I aspired to. He had travelled by dog sled to remote peaks in Antarctica. He had climbed some of the hardest ice routes on Ben Nevis and was one of the few British mountaineers then braving winter climbing in the Alps. Long before it became a glitzy media event, he had, in a single day, skied the famous Glacier Patrol from Zermatt to Verbier. In Asia he was setting new benchmarks for ultra-lightweight first ascents of stunning peaks in Chitral, Hunza, Kulu, Kishtwar names redolent with the promise of exotic adventure.

One of the most notable of those vintage Mountain articles by Rob was an account of the North-West Face of the Gletscherhorn in the Bernese Alps. No Britons had previously attempted this huge ice face lurking behind the Jungfrau in the wild cirque of the Rottal Glacier. In fact it had probably had few ascents at all since it was first climbed in the thirties. So, in purely competitive terms and dont let any climber fool you that he or she does not have at least a streak of competitiveness this was a nice tick to add to the CV. But what comes across in Robs account republished here is not chest-thumping triumphalism, but a sense of delight. Here is someone genuinely loving what he is doing, relishing the difficulties, enjoying the companionship, attuned to every detail of the landscape.

Forty years on, the delight is still there, particularly in his adopted home of Snowdonia. Few people have run, biked and climbed over the mountains of North Wales as assiduously as Rob, and few have observed the landscape so acutely. And few are as knowledgable about its plants and birds. Reading some of his evocative pieces on Eryri reminds me just how special that landscape is, particularly in rare cold winters when snow and ice work their transformative magic. The stories also remind me that you dont have to fly thousands of miles to find enchantment it is right here, on our doorstep. Nor do you have to be climbing some desperate new route at extreme altitude to achieve fulfilment Robs account of soloing that classic rock climb Amphitheatre Buttress in the Carneddau sparkles with the sheer joy of moving through a vertical landscape.

On a more serious note, when we fly round the world in search of ever more exotic adventures, we burn vast quantities of fossil fuels. Mountaineers contribute their fair share to global environmental degradation. Rob has always been aware of and has written about the contradictions inherent in a career that involves taking people into the wilderness, even if he does espouse Schumachers small is beautiful principle, sometimes to the point of extreme spartanism. (A mutual friend once described the depressingly meagre rations served up by Rob each evening, after yet another gruelling days march through the Karakoram). Austerity aside, he is the thinking persons climber, as summarised once by his then boss at the National Mountaineering Centre, John Barry, who described him as a man of culture, a man of peace, a Renaissance man, all the good bits from Chariots of Fire, arrow alpinist, and as fit as a butchers dog a deliberately inappropriate metaphor for a conscientious vegetarian. That pen portrait appeared in an account of the epic first ascent of the East Ridge of Mount Deborah, in Alaska perhaps the hardest and most committing climb in Robs long mountaineering career. Of course Barry is gently poking fun, because that is his style, but the mockery is suffused with obvious affection and admiration for one of Britains great all-round mountaineers. Rob is also a distinguished mountain guide and a fine writer about his chosen way of life. Enjoy these thoughtful, provocative, entertaining evocations of that life.

Chapter 1

In my Backyard

Craig yr Ysfa. The Amphitheatre is the broad gully on the right-hand side.

Photo: John Farrar.

Even in the midst of yet another summer when low-pressure systems seemed to queue up in the Atlantic like jumbo jets at Heathrow, there were isolated days of such perfection that it was easy to forgive and forget the rest of the time. Cycling the shady lanes of the lower Conwy valley on a fine June morning when the air felt pleasantly cool on bare legs and the hedgerows were full of honeysuckle and strident wrens, I was reminded why I have chosen to live most of my adult life in Snowdonia. The car was off the road for its MOT and this was clearly a day to be in the mountains. Making a virtue of necessity, I was making my way through Rowen and Llanbedr-y-Cennin up into Cwm Eigiau. From Llanbedr the Ordnance Survey indicates in bold green dots that the track is a byway open to all traffic but it is clearly not much used. Bracken, cow parsley and nettles clogged my chain and forced me off the bike for fifty metres or so until a sunless tunnel formed by hazel coppice subdued the vegetation and made for easier, if muddier, going. The path, brightly edged now with foxglove, campion, herb robert and vibrant blue veronica, narrowed and dropped steeply down to the Afon Dulyn.

The bouldery riverbed was overhung by oak and ash and felt almost tropical in the green luxuriance with which bark and rock alike were smothered by lichen, moss and fern. I carried the bike across a neat unobtrusive footbridge and up on to an unremittingly steep, twisting council road calling for bottom gear and maximum effort. Gradually the angle eased and, as the high tops of the Carneddau hove into view, the road emerged from birch woodland on to a moor of tussock grass and rush and a few sheep.

With easier cycling and gates to open and shut there was much to see and hear that would have been missed in a car. Simple things like the crimson breast and lovely rufous-brown back of a linnet perched on a gorse bush, the descending cadence of a meadow pipits flight song as it parachuted down to earth, the strange fishing-reel call of a grasshopper warbler, were all familiar enough but at that moment they were a source of wonder and delight. As I pedalled on towards the mountains I was grinning to myself.