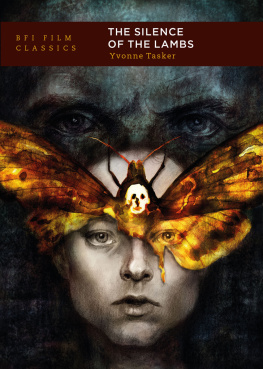

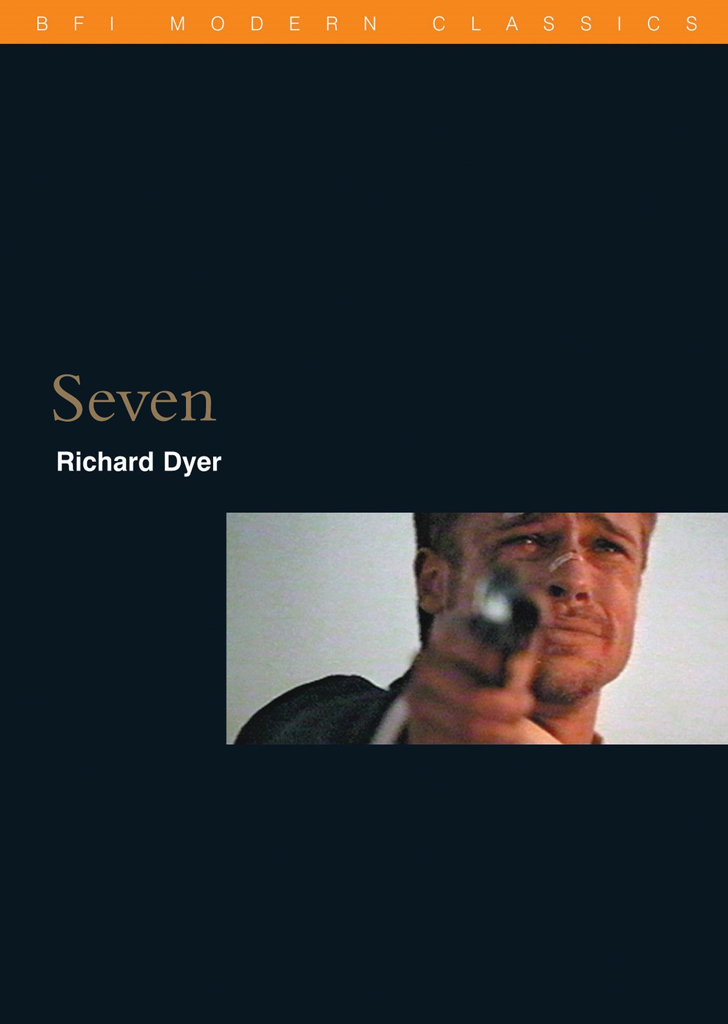

BFI Modern Classics

Rob White

Series Editor

Advancing into its second century, the cinema is now a mature art form with an established list of classics. But contemporary cinema is so subject to every shift in fashion regarding aesthetics, morals and ideas that judgments on the true worth of recent films are liable to be risky and controversial; yet they are essential if we want to know where the cinema is going and what it can achieve.

As part of the British Film Institutes commitment to the promotion and evaluation of contemporary cinema, and in conjunction with the influential BFI Film Classics series, BFI Modern Classics is a series of books devoted to individual films of recent years. Distinguished film critics, scholars and novelists explore the production and reception of their chosen films in the context of an argument about the films importance. Insightful, considered, often impassioned, these elegant, beautifully illustrated books will set the agenda for debates about what matters in modern cinema.

Contents

to Giorgio

I should like to thank the following who have discussed aspects of Seven with me: Jonathan Bignell, Deborah Cameron, Christa Lykke Christensen, Gerry Cousin, Ian Garwood, Neil Jackson, Peter Kemp, Fran Lanigan and Julianne Pidduck, as well as students on my 19978 MA course at Warwick University, respondents to talks at the Universities of Salerno and Saragossa and the Istituto Universitario Orientale in Naples and Marina Vitale, Chantal Cornut-Gentille DArcy and Silvana Carotenuto, Lidia Curti and Iain Chambers, respectively, for inviting me to give those talks. Finally, Id especially like to thank Sissel Vik, whose MA dissertation made me realise how interested I too was in the serial killer motif, Rob White, a vindication of the value of editing, and Giorgio Marini, to whose enthusiasm for the beauty of Seven I hope I have done justice.

Its gonna go on and on and on.

(Detective Somerset on learning of the first murder)

Seven is a study in sin. It is also a crime movie and a film of great formal rigour. The notion of sin connects these generic and stylistic qualities. Crime fiction deals by definition in matters of wrongdoing, but the specific resonance of sin is achieved in Seven by the single-mindedness of the films formal structural, aural, visual choices.

Seven asks to be seen in terms of sin. The title need not of itself indicate this. The seven deadly sins are only one of many significant sevens in Western culture: days of Creation and of the week, cardinal virtues, Christian sacraments, wonders of the world, pillars of wisdom, colours of the rainbow; the Book of Revelation has over fifty groupings of seven (including churches, candlesticks, angels, trumpets) in its vision of the Apocalypse. Nor is this exclusively Western: the Qurn and the Rig-Veda are full of sevens.Seven draws attention to more: Dantes seven terraces of purgation, a reference to seven children slain in something Detective Somerset reads. By being so starkly titled, Seven may want to evoke these quasi-cosmic (even New Age, X-Files) resonances, a vein subsequently mined in a serial killer context by the TV series Millennium. However, it explicitly refers only to sins and days.

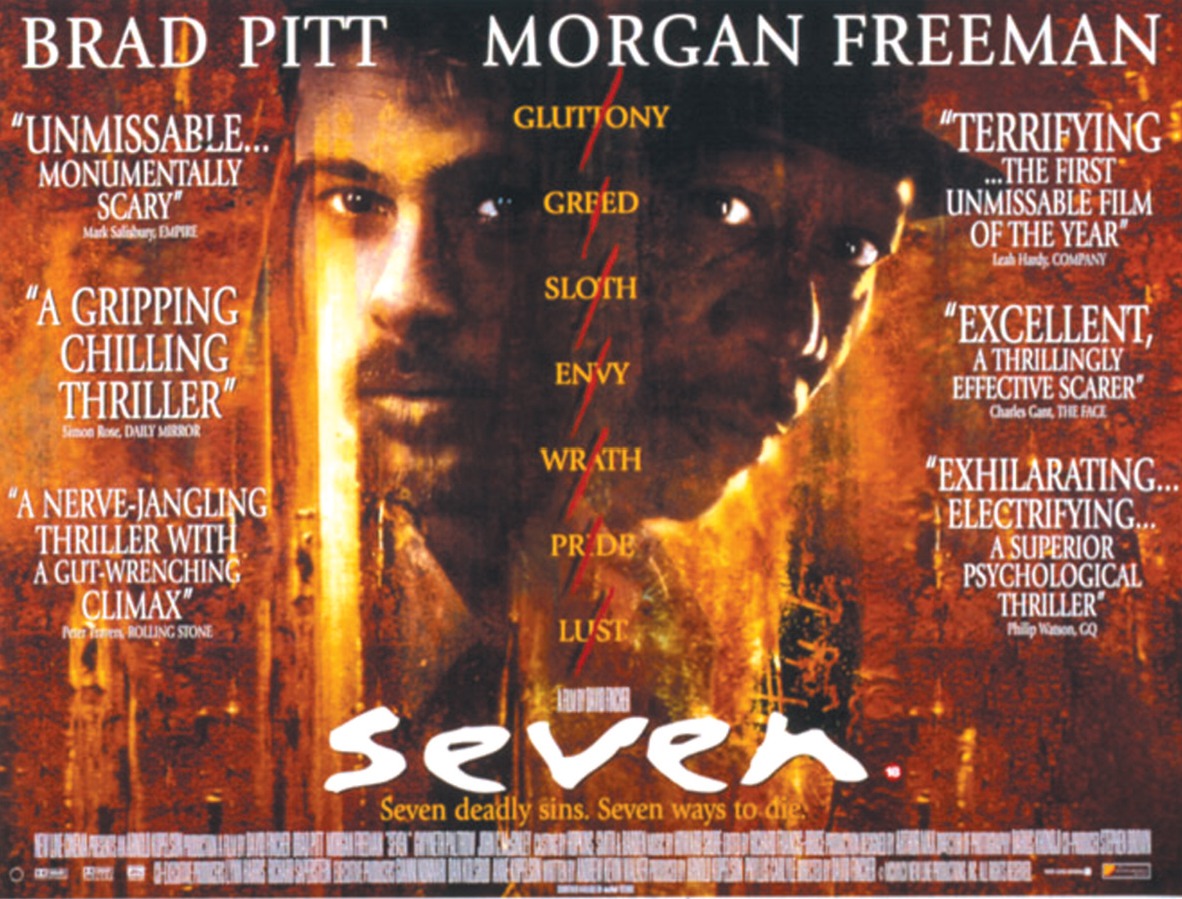

The campaign for the film suggested that the former were the more important. As Chris Pula, head of marketing at the distributors New Line, put it, the sins were the selling point of the film. Important as the drawing power of Brad Pitt and Morgan Freeman was, still the star of the movie was the crime. Brad and Morgan were the co-stars. Yes, their names were there. But we showcased the crime, the seven deadly sins. The most widely-used poster, in turn used for the video box, exemplifies this; a TV campaign flashed the names of the sins up one by one, while a web site gave their more obscure details.

This is good marketing because it understands the product. The film too insists on the primacy of sin. Its central conceit is that of the seven deadly sins used as the basis for seven murders over seven days. This is of course the killers conceit, but it also prompts, through the Morgan Freeman character, Detective Somerset, the wider perception of human frailty evoked by the notion of sin.

Somerset is the site of wisdom in the film. This is so in two senses. First, he is the character in this detective story who is best at detection: he is the first to perceive that the first murder will be one of a series and then its pattern; he tracks the killer down by ingeniously using the public library system (following up on people who draw out apocalyptic and sadistic titles). He is painstakingly methodical, a great brain, as his immediate superior says. This is established by his following up on apparently irrelevant clues in the first murder: bruises on the side of the victims head, grocery store receipts, lino strips found in the victims stomach. These clues baffle or are brushed aside by the other detectives involved: the pathologist, the captain in charge and, most significantly, Somersets new partner Mills (Brad Pitt). However, the importance he attaches to the clues and his interpretation are correct. In narrative terms, he is the one who knows.

His wisdom though is more than investigative acumen. It is in his whole being. He is quiet and still; he is an older man with a soft, saddened face and mellow, resigned voice; he is Morgan Freeman, Miss Daisys chauffeur, Robin Hoods right-hand man, the Shawshank redemption. The film repeatedly cuts to him just looking on, listening, and what he sees and hears is not just clues to a sordid mystery but the worlds iniquity. In a pre-credits murder investigation, he asks whether a boy saw his mother shoot his father, and the detective on duty replies irritatedly:

What kind of fucking question is that? Its always these questions with you. Did the kid see it? Who gives a fuck? Hes dead. His wife killed him. Anything else has nothing to do with us.

But Somerset consistently sees that anything else what it means for a child to see such violence in the family, for instance does have to do with all of us. Again, this sets him apart from those he works with, not just this detective, but Mills with his chatter and restlessness and the cops at the library who would rather play cards than read books.

Somerset has knowledge and wisdom and thus functions as the intellectual and moral voice of the film. This makes all the more significant his relation to the killer, Jonathan Doe (Kevin Spacey). He is not like Doe but he does see the world in much the same way, and what both see is a world drenched in endless wickedness. When towards the end, Mills accuses Doe of killing innocent people, Doe delivers a speech detailing his victims lack of innocence, concluding:

Only in a world this shitty could you even try and say these were innocent people and keep a straight face. But thats the point. We see a deadly sin on every street corner, in every house, and we tolerate it. We tolerate it because its common, its trivial, we tolerate it morning, noon and night.

Somerset shares this sense of the absolute pervasiveness of sin and the worlds indifference to it, even though he does not use the word sin. In a conversation with the police captain, he refers to an incident about four blocks from here, in which a man is out walking his dog, is attacked, has his watch stolen and while hes lying there on the sidewalk helpless, his attacker stabs him in both eyes; the captain shrugs it off as the way its always been. This though is Somersets point: an act of gratuitous cruelty is met with complacency. Its really no better than the sleazy sex club owner who, asked by Mills if he likes what he does for a living, replies No, I dont. But thats life isnt it? and sits back resentful and defiant. This is why Somerset felt the fear he tells Tracy of, when he heard his partner was pregnant How can I bring a child into a world like this?, a world, presumably, this shitty. Later still, in a bar after the Lust murder, he tells Mills, I just dont think I can continue to live and work in a place that embraces and nurtures apathy as if it was a virtue, the equivalent of Does emphasis on the toleration of sin morning, noon and night.