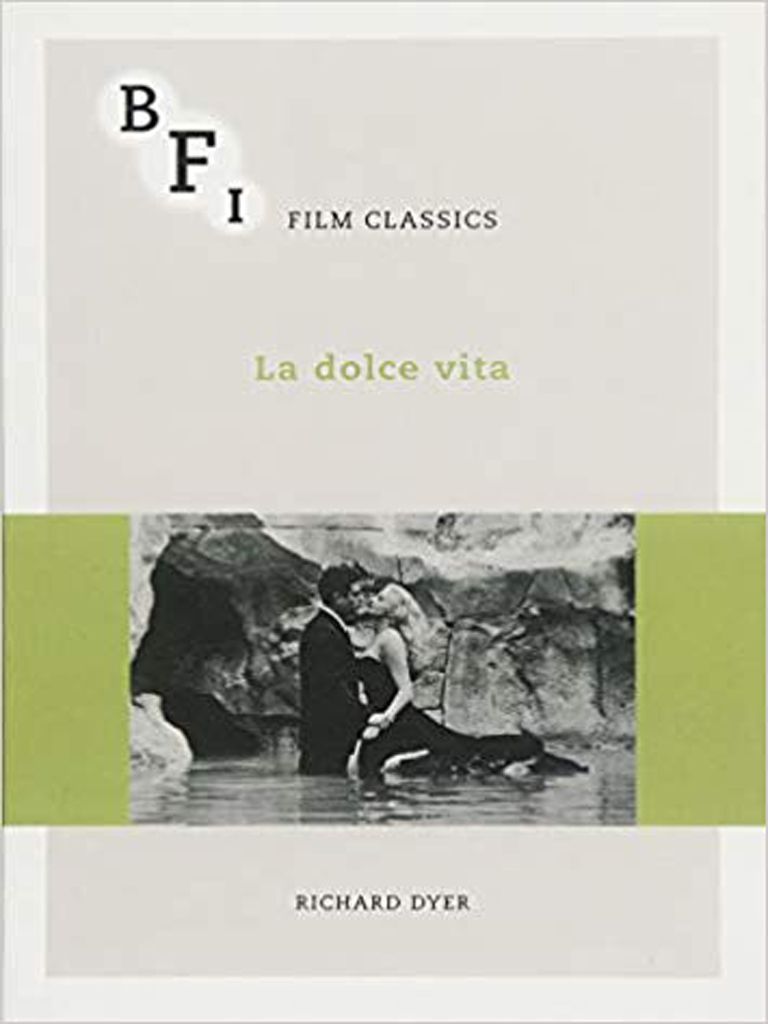

BFI Film Classics

The BFI Film Classics series introduces, interprets and celebrates landmarks of world cinema. Each volume offers an argument for the films classic status, together with discussion of its production and reception history, its place within a genre or national cinema, an account of its technical and aesthetic importance, and in many cases, the authors personal response to the film.

For a full list of titles in the series, please visithttps://www.bloomsbury.com/uk/series/bfi-film-classics/

Contents

I have taught La dolce vita on and off for many years, including at Warwick University and Kings College London, and benefitted from the ensuing discussions. Much of the research for this book was carried out at Indiana University Bloomington, with its astonishing library holdings in Italian culture (and notably film), its superb campus cinema (as a space and as a programme) and the wonderful group who took my course dedicated to the film: Cameron Buckley, Lisa Dolasinski, Ayeshan Julide Etem, Joan Hawkins, Jamie Hook, Katherine Johnson, Russell Sheaffer, Alex Swanson, Brenda Weber and Eric Zobel (and thanks to Leya Taylor for facilitating the audiovisual side of things so well). My thanks for the helpful comments of the anonymous reader for BFI/Palgrave, and to Jenna Steventon, Nicola Cattini, Clarissa Sutherland and the peerless copy-editor Philippa Hudson for seeing it through the editing and production stages so painlessly. Thanks too to Mauro Giori for discussion of the film, notably its queer aspects, and above all to Giorgio Marini, for whom, like me, seeing La dolce vita when it came out felt like a lifechanging experience, as has been my meeting him.

A helicopter, carrying suspended beneath it a large statue of Christ with his arms outstretched, flies over a football field and alongside the ruins of an ancient Roman aqueduct, past high-rise blocks of flats and onwards towards a large domed church; it is followed by another helicopter carrying a journalist and photographer, while on the ground a crowd of youngsters runs along beneath it, yelling gleefully. These are the first two shots of La dolce vita; in considerable measure they encapsulate the film to come.

They embrace accretions of history in Rome like a palimpsest: ancient, imperial Rome, Christianity, popular culture (football), modern architecture, mass media. The helicopters skim over all but the last of these, pressing on to where the films and the medias main attention lies, the sweet life of the rich and glamorous; but the sense that there is a world beyond the latter, the world passed over in this opening, does not leave the film. The image of the Christ statue, perhaps comic, certainly seen as scandalous by many at the time, nonetheless establishes Christianity as a reference point for the film. The proletarian Rome of tower blocks, football, wastelands does not altogether disappear from the film, although, as in the opening sequence, awareness of the citys ancient heritage is increasingly attenuated, eclipsed by contemporary architecture (the high-rise flats, the dome in the distance).

The second shot, lateral tracking with long focal length lens and widescreen, allows more than one element of the palimpsest to be visible and emphasises a sense of depthlessness, two qualities that justify the common recourse to the term fresco to describe La dolce vita. There is also multiplicity of movement the helicopters, the youngsters, the camera and the sound of the kids yelling comes in just at the point of the dissolve between the two shots, giving that sense of a release of energy that starts off most sequences of the film (and then, unlike here, running out of steam). The elegant interplay of movement, the easy fluidity of the dissolve on movement, counteract any portentousness the imagery may hold.

In the very last seconds, the shadow of the helicopter carrying the Christ figure seems to fly up the side of one of the tower blocks. It is an astonishing moment. The logistics required to achieve this effect are daunting, yet in all the accounts of the making of the film there is no reference to how many rehearsals and takes it took to get the coordination of helicopters, extras and camera right. The shots precision seems utterly unpredictable in light of the general impression that making the film was all rush and chaos, and yet such precision is apparent throughout, and always as lightly, glancingly worn.

Like most of the incidents in the film, this is based on one that actually occurred and was reported in the media. Also, characteristically, the activity of the media covering the event is incorporated into the presentation (the journalist and photographer following the helicopter with the Christ figure). Whats more, La dolce vita was itself a media story, before and during its making and on its scandalous release, and has continued to be a media reference point ever since. It is among the most famous films ever made, not because of box-office success (albeit considerable), critical acclaim (insecure) or even how widely it has been seen or remembered (hard to determine), but because the idea of it, the title and certain images (the helicoptered Christ, Anita and Marcello in the Trevi fountain, sunglasses worn indoors or at night) have lodged unshakeably, so far, in the public imagination. No film is more embedded in the specifics of the moment of its making, no film has longer outlasted that moment.

***

La dolce vita consists of a series of sequences centred on Marcello Rubini, a journalist in Rome.

1 . He and the photographer Paparazzo follow a helicopter carrying a statue of Christ to St Peters Basilica, flirting on the way with some young women sunbathing on a rooftop terrace.

2 . Marcello takes notes on celebrities at a nightclub, where he meets an old friend, Maddalena. They pick up a street prostitute, Ninni, and go back to her place for the night. When he gets home, he finds that his live-in girlfriend Emma has tried to kill herself and he rushes her to hospital.

3 . He covers the arrival of, press conference and party for the US film star Sylvia Rank; at Sylvias request, Marcello takes her away from the party, winding up with her in the early morning at the Trevi fountain, which she wades into; delivering Sylvia to her hotel, he is attacked by her fianc, Robert.

4 . During a fashion photo shoot, he catches sight of an old acquaintance, Steiner, and follows him into a nearby church, where they have a conversation.

5 . Marcello, Emma and Paparazzo travel to a village outside Rome, where two children claim to have seen the Virgin, and where crowds, including sick people, and the media await and watch the childrens reappearance.

6 . He and Emma go to a soire at Steiners.

7 . He spends the evening with his father, who is visiting from the provinces. At Signor Rubinis request, he and Paparazzo take him to the Cha Cha club, where they meet Fanny, an old flame of Marcellos; she takes Signor Rubini back to her place, where he has a mild stroke, but leaves for home in the early morning.

8 . Marcello tries to work on a book in a seaside trattoria, where he talks with the waitress, Paola.

9 . Nico, an acquaintance, takes him to a party at her aristocrat fiancs home, a castle in Bassano di Sutri; the partygoers go looking for ghosts, and Marcello meets Maddalena again, but ends up sleeping with Jane, an American painter.