Acknowledgments

W ith gratitude to my spouse, Randolph E. Scott, for his unending support.

Thank you to all others who assisted me in telling this story, including those who participated in interviews for this work: Linda Alband, Edward Alwood, Dr. Marcus A. Conant, Dr. James W. Curran, Dr. William Darrow, Belva Davis, Michael Denneny, Dr. Don Francis, George Greenfield, David Israels, Cleve Jones, Eric Marcus, Ann Neunschwander, Steve Newman, George Osterkamp, Carol Pogash, Michelangelo Signorile, Dr. Mervin Silverman, Susan Sward, and Rita Williams.

Special thanks to members of the Shilts family, including Gary and Judy Shilts and Reed and Dawn Shilts, for all their assistance and support.

Additional thanks to Robert Winder at the Aurora Public Library, Aurora, Illinois; Dr. James Landers, Dr. Patrick Plaisance, Dr. Joe Champ, Dr. Michael Hogan, and Dr. Greg Luft at Colorado State University; Randy Alfred and the GLBT Historical Society Museum and the GayBack Machine Archive, San Francisco; Marilyn Kincaid and the Reverend Cecil Williams at Glide Memorial Church, San Francisco; Christina Moretta and Tim Wilson at the James C. Hormel LGBTQ Center, San Francisco Public Library; Women's, Gender, & LGBTQ+ Studies at the Library of Congress, Washington, DC; Michael C. Oliveira at ONE Archives, University of Southern California Libraries, Los Angeles; Sally Smith Hughes at the San Francisco AIDS Oral History Project, University of California, San Francisco; Alex Cherian and Robert Chehoski at the San Francisco Bay Area Television Archive, J. Paul Leonard Library, San Francisco State University; Wes Haley, Alan Mutter, David Perlman, and Susan Sward at the San Francisco Chronicle; the papers of Dr. Marcus A. Conant and Dr. Selma Dritz in the University of California Digital Archives; Jennifer S. Argo, Marika Christofides, Dustin J. Hubbart, and Daniel M. Nasset at the University of Illinois Press; Alan Brown, Michael Dotten, Jerry Harris, Drex Heikes, Gail Hoffnagle, Greg Leo, Robert Liberty, Joshua Marquis, and Lauren Peters at the University of Oregon Alumni Association; and Duncan McDonald at the University of Oregon, School of Journalism & Communication. I am grateful to Bill Bridges, Bethany Crum Roush, and Sonya Stinson for editing assistance and to Dr. Donald Abrams, Barry Barbieri, Karl Bridges, Dani Castillo, J. Wesley Cunningham, Jennifer Finlay, Jordan Gorostiza, Dr. James Haney, Dr. Debbie Hill Davis, Mary Beth Ikard, Dr. Alex Ingersoll, Gary Kass, Carrie Lozano, Edward K. Moore, Steve Polston, S. Cory Robinson, C. Scott Sickels, Dr. Gerri Smith, Danielle Stomberg, Jonathan Swain, and Scott Walters for special assistance.

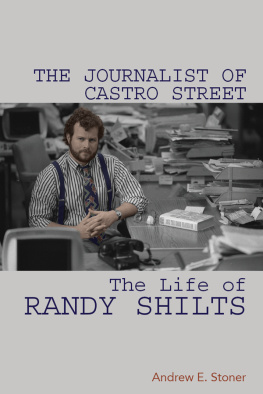

ANDREW E. STONER is an assistant professor of communication studies at California State University, Sacramento. His books include Campaign Crossroads: Presidential Politics in Indiana from Lincoln to Obama.

The University of Illinois Press

is a founding member of the

Association of American University Presses.

____________________________________

University of Illinois Press

1325 South Oak Street

Champaign, IL 61820-6903

www.press.uillinois.edu

CHAPTER 1

Aurora Dawn

R andy Shilts's hometown of Aurora, Illinois, served as the archetypal backdrop for a popular comedy sketch that attempted to portray the realities of idealized American life in the postwar era. Comedian Mike Myers created the character Wayne Campbell and the fictional show Wayne's World for NBC's Saturday Night Live; it later spawned two successful motion pictures. Myers said he was seeking to re-create the hazy, lazy heavy metal days of the 1970s for kids in towns like Aurora, where nothing special ever happened, as they longed for excitement and searched for ways to express themselves.Wayne's World, it seems, succeeded in capturing what it meant to grow up in midwestern American towns such as Aurora during Shilts's adolescence.

Aurora had a problem common in the late 1960s and early 1970s: stagnant population growth and young people leaving town to spread their wings elsewhere. A suburban city hidden in the shadow of Chicago, it proudly claims the title as the second-largest city in Illinois, sprawling across four counties of the northeastern part of the state. The Fox River cuts a sharp dividing line down the center of the city, providing a strong demarcation between east- and west-side neighborhoods and, like many American towns, between those who have and those who have not. Randy Martin Shilts wasn't born in Aurorahe arrived as the third son born to Russell Shilts (whom most people called Bud) and Norma Brugh during a short stint for the young married couple in Davenport, Iowa. While he was still a toddler, Shilts's parents moved to Aurora to make their permanent home. Bud and Norma, both natives of southwestern Michigan, announced their engagement shortly after the Japanese attack on Pearl Harbor and were married in July 13, 1942, when they were both nineteen years old. Bud worked as a welder but had just enlisted for military service for World War II and was soon off to basic training at Fort Campbell, Kentucky. Norma had just graduated high school. The marriage was troubled from the start. My father told me that they got married just before he went into the service, and when he came back he was ready to pack it up and just forget it and leave her in Michigan, Randy Shilts's oldest brother, Gary Shilts, said. Bud changed his mind and didn't leave Norma. The family followed Bud's job opportunities as they popped up in Michigan, Iowa, and Illinois before settling in Aurora. Bud came back from his military tours a little wiser and a lot more cynical about the realities of life. While in Europe, he had toured the Jewish concentration camp at Dachau in southern Germany after Allied forces liberated it. He was just overwhelmed, Gary Shilts believes. He was this rural Michigan kid, and he was unsure of what kind of prisoners these were, these men, women, and children. Someone told him that these were Jewish prisoners, that they were Jews. He was just dumbfounded. It astounded him. He had thought of Jews only as these characters in the Bible, not an actual race of people. His worldview expanded quickly amid the ugly aftermath and ruin of the Nazi regime in Germany.

Back home, by all accounts, Bud Shilts was generally a successful salesman whose dreams of being an architect were frustrated and unfulfilled. He took various sales jobs for lumber companies and later for firms selling manufactured or prefabricated homes. For extra cash he would copy architectural designs he obtained and then ask a licensed architect friend to sign them. Bud then quietly sold the plans on the side to friends and others wanting to save some money on construction costs, Gary said.

We lived in what some sociologists call a boardinghouse family, Gary Shilts said. Everyone just sort of did their own thing. There wasn't that much interaction among family members, the exception being frequent discussions of politics.

Bud's growing doubts about God and the remnants of a youthful wanderlust cut short by a young marriage and a military tour resulted in his evolving desires colliding with Norma's assigned role as a mother and homemaker. This protected, closed environment allowed Norma to nurse the secrets of alleged sexual abuse she experienced as a young girl, but it still left her feeling trapped. Bud engaged in affairs with women outside his marriageaffairs that weren't always well concealed from Norma. As a result, eldest son Gary believes his mother had good reason to be drunk all the time. My dad was having a party and she wasn't included.

Norma Shilts was born Norma Jean Brugh near Kalamazoo, Michigan, and met a fellow West Michigander, Bud Shilts, at a high school football game, where he was a cheerleader. The marriage was a happy one until 1945, and the end of the war, and the two of them (and me) actually had to live with one another, Gary Shilts said.