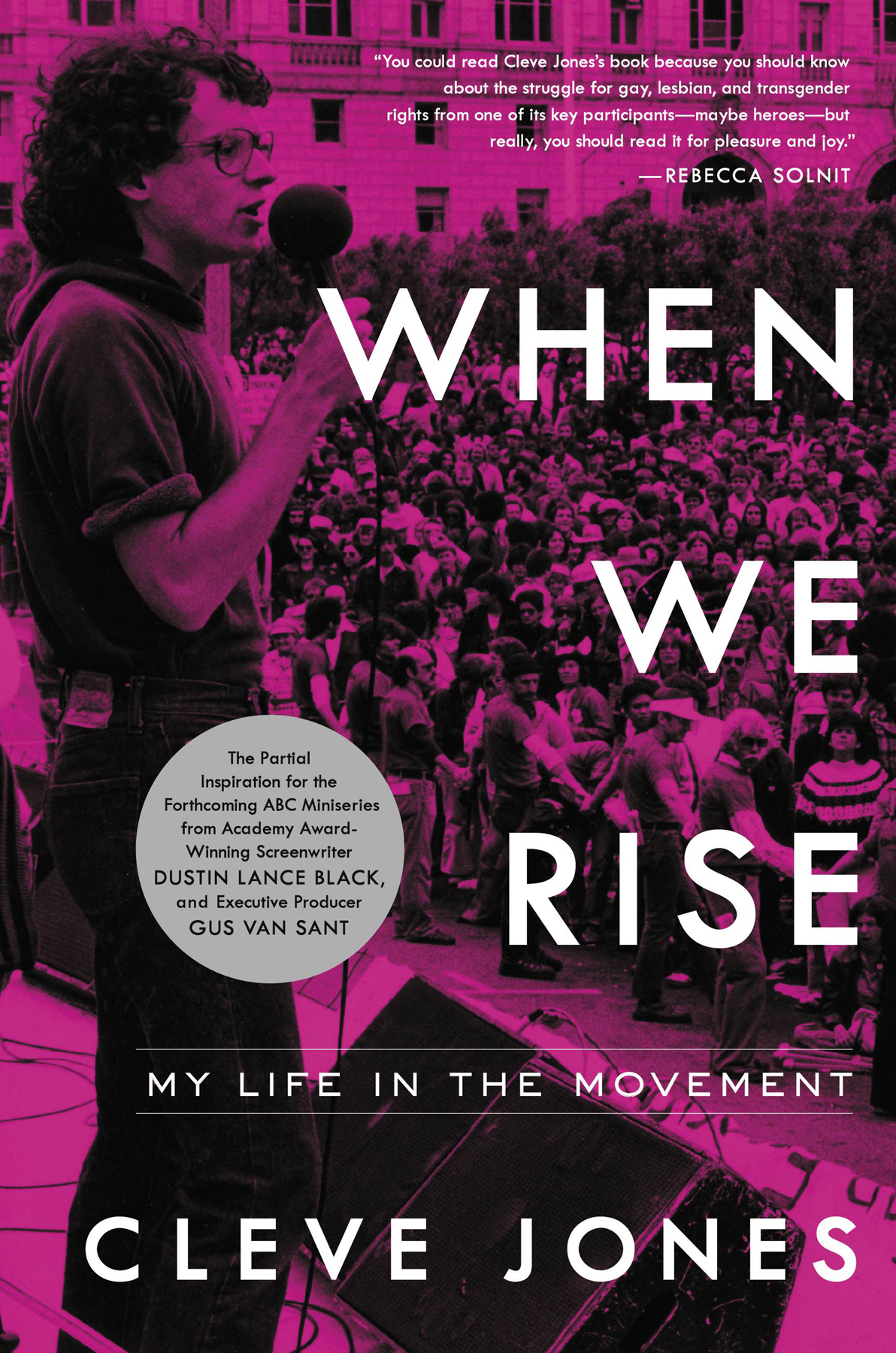

The movement saved my life.

I signed up in 68, when I was 14 years old. Like other young people across the United States, I wanted to do my part to end the war in Vietnam. My family had just moved from Pennsylvania to Arizona and when Cesar Chavez and the United Farm Workers came to organize the grape pickers, my friends and I knew right away that it was part of the bigger picture and signed up for picket duty and walked in the marches.

It took a while for word of the womens movement to reach us in the Arizona desert but when we heard about it we joined that call, too, circulating petitions for the Equal Rights Amendment and speaking out against rape, sexual harassment, and wage inequity.

It wasnt until 1971 that I learned that part of the movement was especially for people like me. I read about it in the Year in Review1971 issue of Life magazine in my high school library while skipping gym class. Gym wasnt a safe place for me; I didnt get beat up much but the threat was always present. I invented a mysterious lung malady to persuade our family physician that I was too ill to attend physical education. Instead, Id spend the hour in the library reading magazines or pretending to study while trying to remember to cough every few minutes.

I am pretty sure that was the exact moment I stopped planning to kill myself.

I WAS BORN INTO THE LAST GENERATION OF HOMOSEXUAL PEOPLE WHO grew up not knowing if there was anyone else on the entire planet who felt the way that we felt. It was simply never spoken of. There were no rainbow flags, no characters on TV, no elected officials, no messages of compassion from religious leaders, no pride parades, no It Gets Better, no Glee, no Ellen, no Milk. Certainly no same-sex couples with their kids at the White House Easter egg hunt. Being queer was sick, illegal, and disgusting, and getting caught meant going to prison or a mental institution. Those who were arrested lost everythingcareers, families, and often their lives. Special police units hunted us relentlessly in every city and state. There was no good news.

But there were a lot of words, cruel words, hurled on the playground and often followed by fists. They were calling me those words long before I had a clue what they meant. Then one day when I was about 12, one kid kept calling me a homo.

Near tears, I yelled back, What does that even mean?

He said, Youre a homosexual and youre going to hell. So I went to my fathers libraryhe was a professor of clinical psychologyand looked it up. I remember vividly the shame of reading that I was sick, psychologically damaged.

By 12 years old I knew that I needed a plan. The only plan I could imagine was to hide, never reveal my secret, and, if discovered, commit suicide.

I graduated from high school, barely, in June 1972 and traveled to Ghost Ranch, New Mexico, for a gathering of Quakers called the Inter-Mountain Friends Fellowship. My mother and I had started attending the Phoenix Friends Meeting a few years earlier. Supposedly some of my fathers ancestors had been Quaker, but my artistic but practical mothers main motivation was avoiding conscription. In the early 1970s all young men were required to register for the draft at 18, and thousands were sent against their will every year to fight, kill, and die in Vietnam. It was my worst nightmare: gym class with guns and rednecks in a jungle. Mom knew that Quakers and members of other peace churches like the Mennonites and Jehovahs Witnesses were being granted conscientious objector status that kept them out of the war. My family was not religious, but we opposed the war. My paternal grandfather, Papa, was even willing to move us all to Canada rather than see me, his first grandchild, sent to war or forced into exile alone.

As it happened, I loved the Quakers, loved the silence of Meeting for Worship, and loved the principles of simplicity and peace by which they lived. From the Friends I learned the history of nonviolent resistance and civil disobedience in the struggles against war and for peace and social justice. In the Meeting I also found some friends and even a boyfriend of sorts for the last two years of high school.

A few weeks after graduation, I joined some of the Quakers on a VW bus trip. We sang along to Don McLeans American Pie and rode across the desert to New Mexico for a few days retreat at Ghost Ranch near Taos. The land there is magnificent, and I spent hours every day hiking the mesas by myself in between various meetings and discussions, mostly about the war and the civil rights movement.

I met a guy named Mel there. He was older than me, and taught at a college in Logan, Utah. We went on walks together and talked about politics and literature. We shared a love for Hermann Hesse novels and the Moody Blues and talked about books with the excitement that was typical of young people then. One day Mel confessed to me that he was probably bisexual and I told him that I probably was, too. We exchanged addresses and promised to stay in touch after the conference ended and I returned to my family.