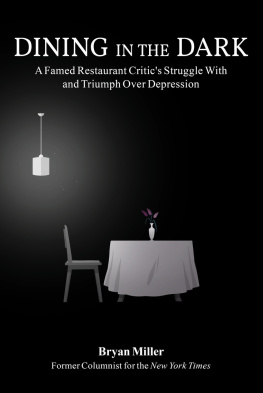

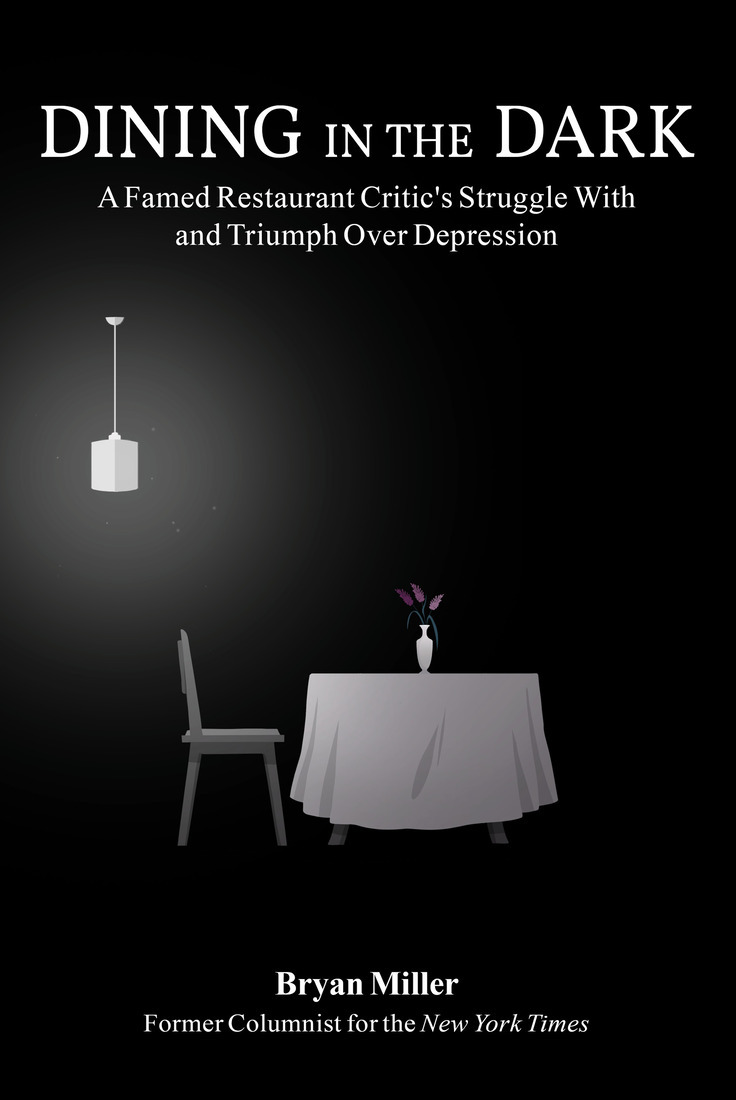

Copyright 2021 by Bryan Miller

All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced in any manner without the express written consent of the publisher, except in the case of brief excerpts in critical reviews or articles. All inquiries should be addressed to Skyhorse Publishing, 307 West 36th Street, 11th Floor, New York, NY 10018.

Skyhorse Publishing books may be purchased in bulk at special discounts for sales promotion, corporate gifts, fund-raising, or educational purposes. Special editions can also be created to specifications. For details, contact the Special Sales Department, Skyhorse Publishing, 307 West 36th Street, 11th Floor, New York, NY 10018 or .

Skyhorse and Skyhorse Publishing are registered trademarks of Skyhorse Publishing, Inc., a Delaware corporation.

Visit our website at www.skyhorsepublishing.com.

10 9 8 7 6 5 4 3 2 1

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data is available on file.

Cover design by Kai Texel

Print ISBN: 978-1-5107-6039-4

Ebook ISBN: 978-1-5107-6040-0

Printed in the United States of America

Words are for what other people have been through, and nobody who has been through this particular experience has ever been able to convey it to anyone who hasnt, perhaps for the simple reason that it has no features to speak of. It is Nothing the Nth power; Nothing heightened to the screaming point.

Wilfrid Sheed

TABLE OF CONTENTS

CHAPTER 1

The Beard Award

F OR THOSE GRAPPLING WITH DEPRESSIVE ILLNESS , life is largely about showing up. Social interactions can be exquisitely painful, and much of ones time is taken up contriving ways to avoid them. For more than a dozen years at the New York Times , my life was consumed by high-profile work and endless socializing. I reviewed restaurants five to six nights a week in the company of one or two couples; had lunch two to three days a week; reported food stories; wrote a weekly recipe column, a weekly kitchen equipment column, and magazine features; this was augmented by public speaking, a daily radio spot, and a weekly TV appearance. I am surprised they didnt draft me as an auxiliary truck driver. I held what was widely considered the best job in food journalismindeed, the best job in the country, period. In the span of nine years as the Times restaurant critic I dined out more than 5,100 times, not counting the company cafeteria and food trucks. Greater New York City was my peachbut it had a dark, moldy underside.

In 1982, I was felled by what might be called a double helping of mental illness. Typically, one is plagued either by a biochemical depression, caused by inexplicable changes in brain chemistry, or an emotional disturbance arising from personal loss, separation, anxiety, or other factors. We know a tremendous amount about the physical brainhow it communicates with various parts of the body, where information is stored, and how it responds to stimuli and medications. But when it comes to the etiology of depression, the why it is tormenting nearly one in five American adults as I write this sentence, there is so much to learn.

Remarkably, despite my dread of socializing, I never failed to show up for a restaurant review. At times I would stand at the front door, breathing heavily like a prizefighter before the bell, heart throbbing, brain on fire. I repeated to myself that I could do it, had done so hundreds of times, and that it would pass quickly. It could take a while, but I always went in.

Outside of professional eating, however, there were numerous vanishing acts, from the minor (private dinner parties, sports events, work functions) to the major (media interviews, business travel, social engagements). To this day I suspect there are some incensed Canadians in Ottawa who, in 1993, invited me to be the keynote speaker at a big gourmet gala, four hundred guests. It sounded like fun five months in advanceas do many such invitationsuntil the date approaches. Crushingly depressed, I made it as far as the United Airlines boarding gate.

Taking a seat near the ticketing desk, I weighed the consequences of going to Ottawa versus not going to Ottawa. If I were to go, and suffer through the event, delivering a halting, semi-coherent speech, at least I would find two thousand dollars in my pocket. Going straight home, on the other hand, would be capitulating to the disease. As the last stragglers trundled through the gate, the attendant, a middle-aged lady with tight hair and a pinched smile, turned to me. Was I on this flight?

No, no, I made a mistake. Its the next one.

Three years into the illness, and between wives, I had drifted far from the shores of optimism regarding an imminent cure. The medicationsanywhere from seventy to 114 pills a weekcould be like an overmatched prizefighter, effective in the early rounds but ultimately weak-kneed and feckless. At times they left me a trembling, withered old man. Climbing the stairs to my third floor apartment could be a five minute trek. Psychotherapy was bearing some fruit, though as yet barely enough to make a small cobbler. Grimly, I came to expect the worst, and it was worse than I expected.

In 1991, the James Beard Foundation anointed me with one of its two highest honors, the James Beard Foundations Whos Who of Food & Beverage in America , awarded to a most accomplished food and beverage professional in the country. I had been at the Times for just over six years, five as the restaurant critic. It seemed a little early to get a career tribute like that, sort of like being voted into the National Baseball Hall of Fame when your rookie contract runs out. The honor came with a large bronze trophy the weight of a young St. Bernard, in the form of a French waiter.

The Beard Foundation, a non-profit culinary organization that likens itself to the motion picture academy, bestows annual awards to chefs, restaurateurs, wine professionals, journalists, and other industry types. It started in the mid-1980s with a couple of dozen honors and was put on in a hotel. Today it is nearly out of control, a Woodstock of self-congratulations. Fueled by corporate sponsorships and media hype, it runs on for days and attracts foodies from as far as Hawaii. In 2017, medals were bestowed upon many dozens of chefs, restaurants, and media.

The Beard Foundation is not alone. Over the past thirty years the food and wine industry has become a Santas sack of tributes and prizes: the S. Pellegrino Almost Famous Chef award, the Food Service Consultants award, the International Food & Beverage Forum award, the Master of Aesthetics of Hospitality Award, and National Restaurant Associations Kitchen Innovation Award Lamb Jam (I do not know what it is either). One gets the impression that today, if you are in a position of some authority in the food business, and hang in there long enough without conspicuously embarrassing yourself, it is hard not to win a prize. I stopped attending the Beard awards in the early 1990s. Sitting that long, my ass went numb.

Two days before the event I was browsing in a guitar shop near Times Square. A familiar bell chimed in my brain. First there was a tingling on the surface of the scalp, like a mild electrical current; then confusion, followed by great anxiety. Before long, a cognitive thunderstorm rolled in, knocking down power lines and making a mess of things. My racing thoughts were random and unfocused and frightening the wonderful assortment of guitars hanging on the walls could have been cured hams. I was certain I had forgotten how to play, so what was I doing there? I wanted to go home and sleep until it passed, but that was wishful thinking. In its wake arrived a thick, gauzy foga dull, stultifying nothingness that Emily Dickenson described as a so-called funeral in the brain.

Next page