Table of Contents

Dedicated with love to

Nilufer, Rustom,

Tehmina and Avaan

Contents

Authors Disclaimer

This is a work of creative non-fiction based on a true story. In order to move the story forward and create dialogue, some fictional characters were created. All such characters are indicated by an * after their first appearance. Any resemblance to actual persons is co-incidental.

Foreword

by

Dr Farokh E. Udwadia

T HE 24TH MILE IS a well-crafted book that grippingly describes the carnage, devastation and misery that took place when the Japanese invaded Burma, the defeat of the British Armed Forces and the ultimate capitulation of the country to the Japanese in World War II.

It revolves around a remarkable human being: Dr Jehangir Anklesaria. Dr Jehangir, a port health officer in Rangoon, lost all his possessions following the Japanese capture of that city. Although he managed to send his wife and daughter back to Bombay, he remained in Rangoon with the retreating British Army and the thousands of refugees fleeing the Japanese holocaust and trekking towards India. During this retreat, Dr Jehangir showed exemplary courage, a single-minded devotion to duty and, above all, an endearing humanity towards one and all, particularly the sick, the suffering and the dying.

As was anticipated, the flood of refugees trekking vast distances through difficult terrain led to epidemics, notably cholera, which, besides being deadly, is extremely infectious. Dr Jehangir, who had trained at Cambridge in tropical medicine and public health, helped in the prevention of this disease and controlled it as best as possible, working in the most primitive and dangerous conditions. I imagine that this must have been a Herculean task, because of the scarcity of resources, difficulties in administration and problems in medical management. He managed to commandeer a large supply of cholera vaccine, ensuring the vaccination of one and all as the main preventive measure, and housing thousands of refugees in makeshift camps.

Devising numerous innovative ways to control and prevent the spread of the epidemic was a stupendous task brilliantly and successfully executed by this doctor, with the help of his trusted group of workers. If the cholera outbreak amongst the thousands of refugees who accompanied the retreating British forces had not been controlled, it could well have spread to army personnel, decimating the British armed forces, which would not have lived to fight another day.

Dr Jehangir travelled a great distance from Rangoon towards the Assamese border in his trusted Austin car. The latter was commandeered at the point of a gun by some rogue soldiers after many days. He had to complete the remaining journey on foot.

This book derives its title from Dr Jehangirs trek through 24 miles of thick tropical jungle across mountains and valleys in furious monsoon conditions, battling hunger, fatigue and daily bouts of fever with rigours closely resembling malaria. He was seriously ill, managing to stay upright on a daily dose of quinine. To have ultimately conquered the 24th mile showed his indomitable will, determination, courage and character, as also his love and devotion towards his wife and daughter. It was this love that kept him going and helped him overcome the grave hardships on this trek. This author introduces a delightful silent conversation between this desperate doctor and his alter ego, which is often combative and which perhaps pushed him to the limits of his physical, mental and emotional endurance, enabling him to ultimately complete the last of the 24 miles.

In my opinion, Dr Jehangir is an unsung hero except, of course, to those who knew him well, and to the thousands he helped selflessly during the retreat from Rangoon. I feel this book should be read by one and all. In current times, when many aspects of modern living have poisoned young minds and blunted their sensitivity and sensibility, Dr Jehangir stands out as a beacon of light, showing how life should be lived and enjoyed without losing sight of ones duty, devotion, courage and humanity. His life illustrates the beauty, spirituality and strength of his Zoroastrian faith, which propelled him to live the life he lived, practising the essence of his religion: good thoughts, good words and good deeds.

Dr Farokh E. Udwadia is a senior consulting physician in Mumbai and the author of numerous books on medicine. In 1987, he was awarded the Padma Bhushan for his contribution to medicine.

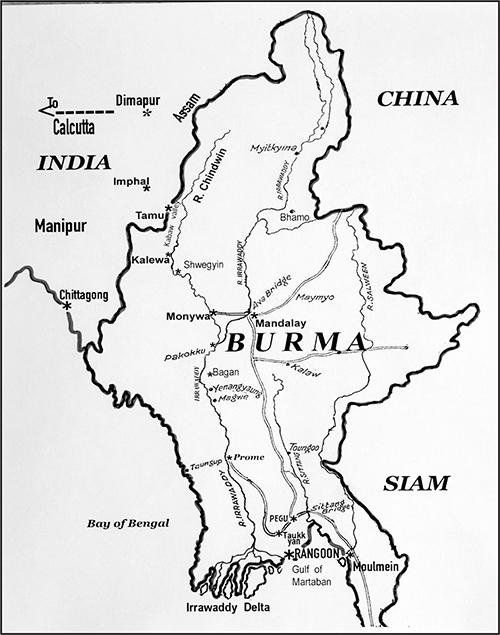

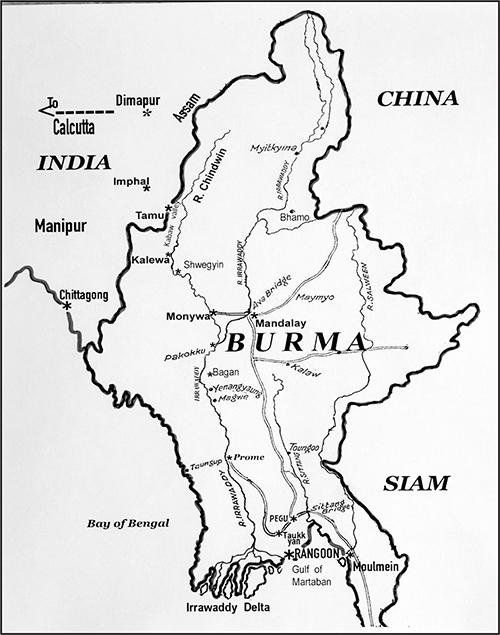

Burma, 1942. Illustrating places pertinent to the story.

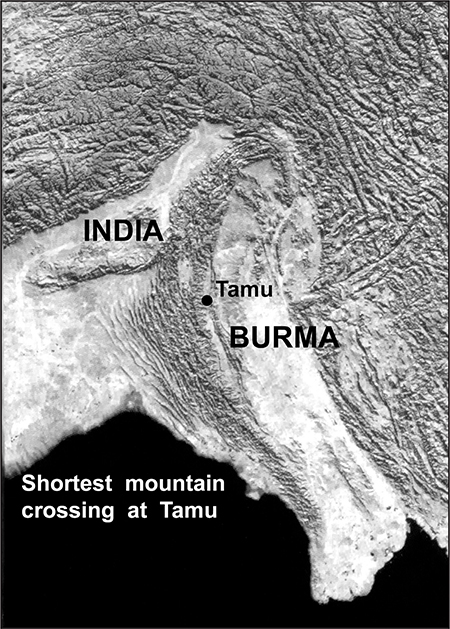

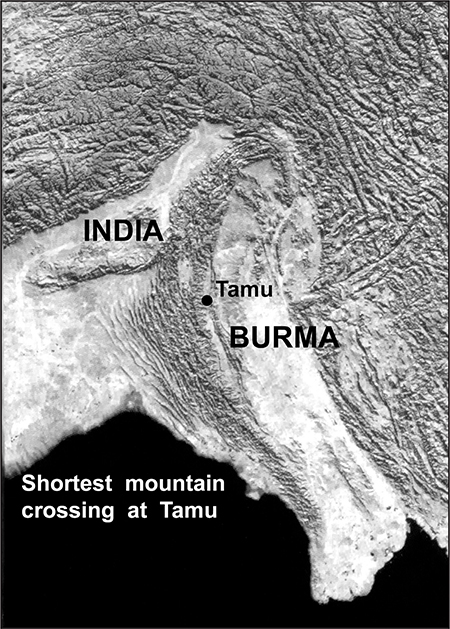

Mountains surrounding Burma.

D R JEHANGIR ANKLESARIA WAS dead. An itinerant refugee from Burma brought Goola the news that she was now a widow. Goola had never met this man, Ramesh*. But he told her that he knew her husband, and that Jehangir had been very kind to his family, which was not unlike him. He had given them a ride when they very much needed one.

Rameshs voice quivered as he spoke. Ammah, he saidhe had lost his own mother in the recent hellish journey across the mountains between India and Burma, and now addressed Goola as if she were his parentAmmah, I saw the car, your car, the Austin. There must have been over a thousand bullet holes. All four Japanese planes must have shot at it. The soldiers inside, their bodies were red pulp. And Doctor Sahib was driving, I am very sorry to say.

When they discovered the car, Rameshs mother, even in her frail state, had implored him to find Jehangirs family and let them know. Now he had completed his mission; he was simply repaying the kindness Jehangir had extended to them when he gave them a lift in the Austin.

For a few secondswhich felt much longerall the occupants of The Shelter, where Goola lived, were rendered speechless. Then came the hail of questions: when, where, how

It was the middle of May 1942. The monsoon had drenched north-west Burma, but was still a month away from their home in Bombay.

The table fan struggled to push the humid air around the second-floor veranda.

Goola sat down. Her daughter, Khorshed, remained standing with an arm firmly around her mother as tears welled in her eyes. She had inherited the steel in her character from her father.

Goola cleared her throat and wiped at the veil of tears coating her cheeks. My Jehangir dead? Me a widow? Never! she declared. She was an educated woman, and in that instant remembered the statement attributed to Mark Twain: The reports of my death are greatly exaggerated. Indeed, she thought.

When she spoke again, her tone was subdued. Ramesh bhai, she said, with the trace of a smile, I hear what you are saying. But you dont know my husband. Jehangir would never allow those Japanese to kill him. And that was that, as far as she was concerned. Now come, Ramesh bhai, she continued, you all must be so tired.

Yes, Ammah. We catch the train to Surat in the morning.

You and your family will stay with us tonight. We have a spare room downstairs, Goola said. And now, you must eat after your long journey from Calcutta. You know, my daughter and Iwe also came from Calcutta by train. But we didnt cross the mountains. We came by ship from Rangoon. That was twono, four months ago.