Copyright 1983 by Amos Oz and Am Oved Publishers Ltd

English translation copyright 1983 by Amos Oz

Glossary copyright 1983 by Harcourt, Inc.

All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic or mechanical, including photocopy, recording, or any information storage and retrieval system, without permission in writing from the publisher.

For information about permission to reproduce selections from this book, write to or to Permissions, Houghton Mifflin Harcourt Publishing Company, 3 Park Avenue, 19th Floor, New York, New York 10016.

www.hmhco.com

1993 Authors Note copyright 1993 by Amos Oz and Keter Publishing House Ltd.

English translation copyright 1993 by Amos Oz.

Reprinted by permission.

Postscript copyright 1992 by Amos Oz.

The postscript was a Tanner Lecture on Human Values presented at the University of Michigan on November 12 and 13, 1992, and published as part of The Tanner Lectures on Human Values, vol. 15, University of Utah Press.

The Library of Congress has cataloged the print edition as follows:

Oz, Amos.

In the land of Israel.

Translation of: Poh va-sham be-Erets-Yisrael bi-setav 1982.

A Helen and Kurt Wolff book.

1. IsraelSocial life and customs.

2. National characteristics, Israeli.

I. Title

DS112.0913 1983 306.095694 83-12940

ISBN-13: 978-0-15-648114-4 (pbk.)

ISBN-10: 0-15-648114-6 (pbk.)

eISBN 978-0-547-54077-1

v3.0717

Authors Note to the Original Edition

THE JOURNEY that resulted in these articles took place in October and November 1982. None of the conversations presented here were taped. None of them are presented in full, because they were long. I usually wrote things down as they were said; in one or two instances I wrote things down immediately after the conversation. All of the speakers are alive and well, both those who are mentioned by name and those who are not.

All of the articles, except for the last one, were published serially in the Davar weekend supplement in November and December 1982, and January 1983.

I do not consider these articles to be a representative picture or a typical cross-section of Israel at this time; I do not believe in representative pictures or typical cross-sections. Every place is an entire world and every man is a world in himself, and I reached only a few places and a few people, and even then I was able to see and to hear only a little of so much.

Hulda, March 1, 1983

Authors Note to the Harvest Edition

ELEVEN YEARS HAVE PASSED since the journey that resulted in this book. I never intended to draw a socio-ideological picture of Israel. This was a deliberate journey to the fringes, not a study of the average. Today I am more convinced than ever that no collection of conversations and impressions can possibly represent the spirit and atmosphere of a period of time or of an entire country.

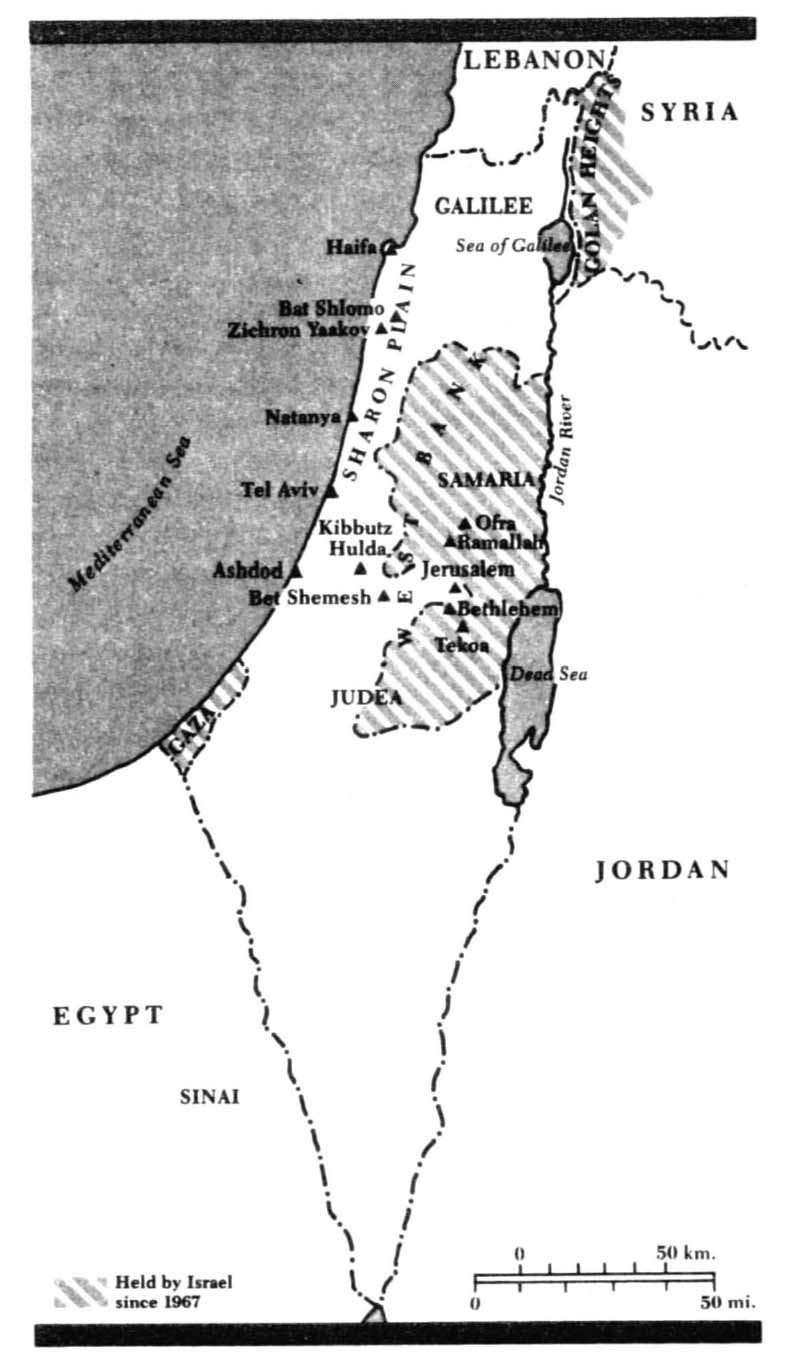

Of the conversations in this volume, not one took place in or around Tel Aviv, in the Negev, or in Galilee. I visited the coastal plain, where three out of four Israelis live, only in the last chapter, so this was a journey almost solely to Jerusalem and to the mountainous regions north, south, and west of it. It was a journey among people of strong convictions, individuals inclined to exclamation points. It was also a journey to areas where men hardly ever let women put in a word.

What has changed between then and now? I can offer no general answer. Nor can I say what might have changed for those I spoke with in the book, because I have not been in touch with most of them since.

Individuals given to exclamation points are still all over the place, particularly in the mountains, loud and clear as ever, sometimes engaged in dangerous actions. Some of the questions that looked open eleven years ago remain openperhaps even more open now than they were then.

I still maintain essentially the same views I expressed in An Argument on Life and Death in Ofra. And I still cling to the hopes I expressed in the last few pages of this book. Some of these hopes may seem a little closer these days.

Arad, June 1993

Translators Note

I WISH TO THANK the author for his invaluable help in translating this book. His assistance and advice made my work a pleasure, a journey in itself. But any shortcomings in the translation are mine alone.

Thank God for His Daily Blessings

IN THE GEULAH QUARTER of Jerusalem, on Rabbi Meir Street, imprinted on one of the metal sewer covers is the English inscription City of Westminstera reminder of the British Mandate in Palestine. The grocery store that was here forty years ago is still here. A new man sits there and studies Scriptures. It is after the High Holy Days: in Geulah, in Achvah, in Kerem Avraham, and in Mekor Baruch, the tatters of the flimsy booths built for the Feast of Tabernacles are still visible in the yards. Their greenery has faded and turned gray. There is a chill in the air. From porch to porch, the entire width of the alleyways, stretch laundry lines with white and colored clothes: these are the eternal morning blossoms of the neighborhood in which I grew up. The Kings of Israel Street, which was once Geulah Street, throbs with pious Jews in black garb, bearded, bespectacled, chattering in Yiddish, tumultuous, in a hurry, scented with the heavy aroma of Eastern European Ashkenazi cooking. An ultraorthodox woman, young, very pretty, pushes a twin baby carriage full of plastic-net shopping bags with bread, vegetables, canned goods, fish wrapped in newspaper, bottles of wine, cooking oil, soft drinks. Her hair is modestly covered but her fingers are richly adorned with rings. She stops to chat with another woman in one of the courtyards in a mixture of Yiddish, Hebrew, and English.

Er iz a meshuggenerhes crazy. He came back here from Brussels mit di gantze mishpochehwith his whole family. Poor Esther. A Brooklyn accent in a figure from Lodz or Krakow. The other woman, behind the fence, answers in English, Its a shame.

New people, but the alleys and the courtyards are virtually unchanged. During my childhood, Eastern European intellectuals and educated refugees from Germany and Austria used to live here side by side with the ultraorthodox. There were artisans here, and scholars, trade-union functionaries, National Religious Party hacks and dedicated Revisionists, clerks in the Mandatory government and workers in the Jewish Agency, members of the Haganah and the Irgun, youth from Betar and the United Socialist Movement and the Bnai Akiva, the religious youth movement, noted scholars, village fools, madmen burning with prophetic light, world reformers who would compose and dedicate to one another fiery brochures about the brutal realities of Zionism, or about how the Palestinian Arabs originated from the ancient Hebrews, or about the blessings of organic vegetarianism. Almost every man was a kind of messiah, eager to crucify his opponents and willing to be crucified for his own faith in turn.

All of them have gone. Or changed their minds. Or pulled up their roots from here and gone to more moderate places. But they left behind them a vibrant Jewish shtetl. The potted plants so carefully nurtured by enthusiastic would-be fanners have long since died. The gardens and pigeon coops have gone to rubble. In the courtyards stand sheds of tin and plywood and piles of junk. Yeshiva students, Hasidim, petty merchants have overflowed into this place from the Meah Shearim and the Sanhedria quarters, or bunched up here from Toronto, from New York, and from Belgium. They have many children. Most of the children, even the littlest ones, wear glasses. Yiddish is the language of the street. Zionism was here once and was repelled. Were it not for the stone, and the olive trees and the pines, were it not for that particular quality of light in Jerusalem, you might think you are standing in some Eastern European Jewish

Next page