Table of Contents

In memory of my parents,

Sam and Maisie Levy,

and for my children,

Daniel and Tanya

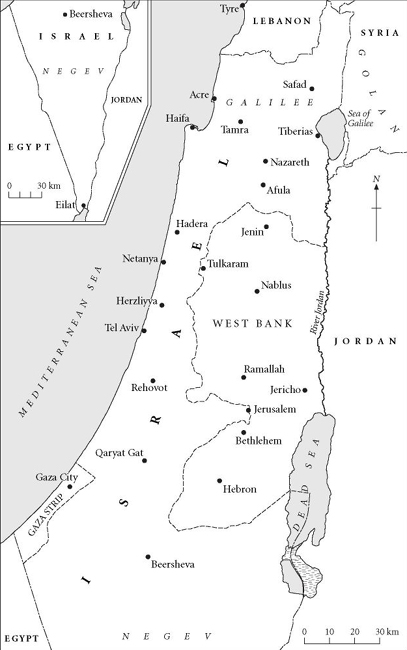

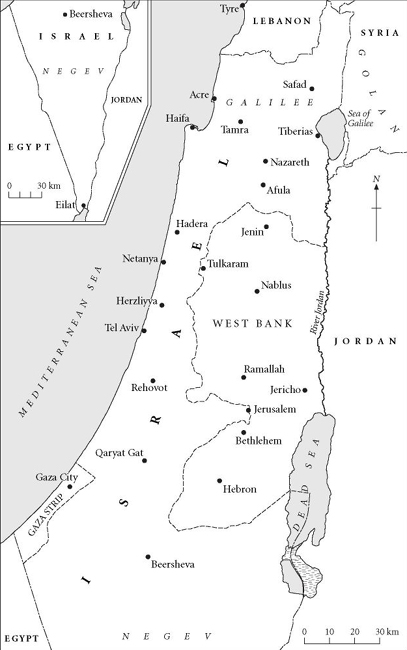

The State of Israel

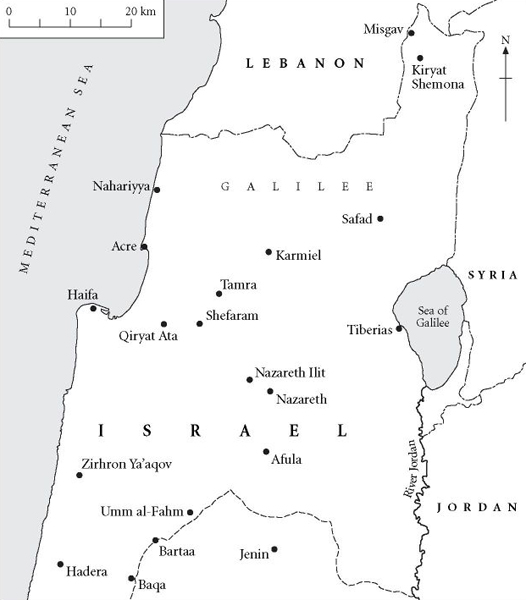

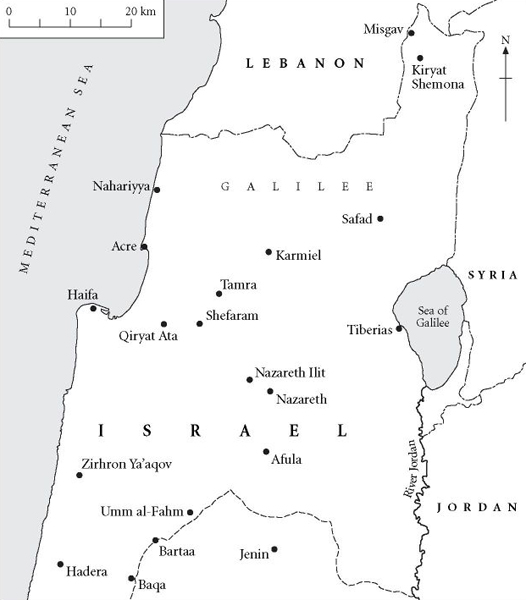

Northern Israel, including the Galilee

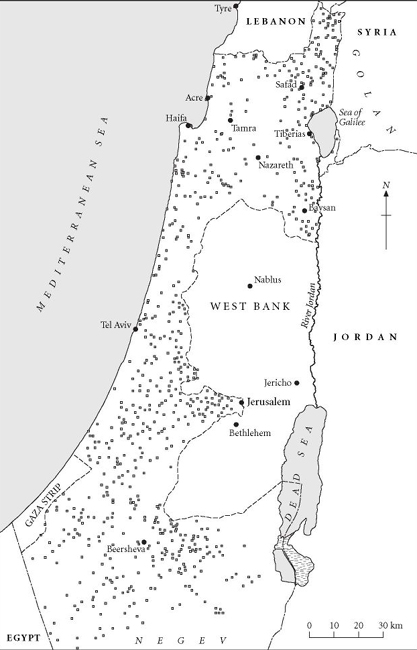

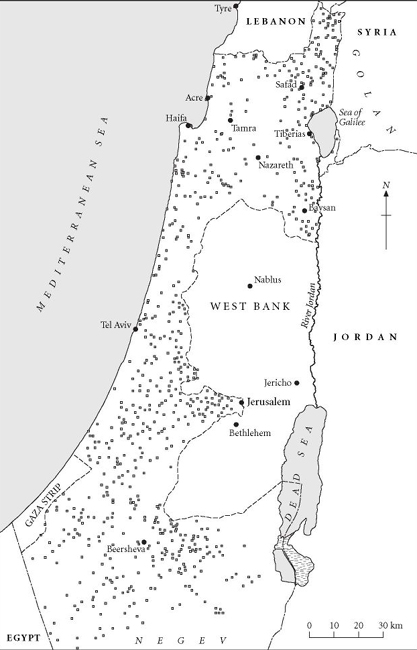

Palestinian towns and villages depopulated during the foundation of Israel in 1948

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

It was a sweltering July night nearly two years ago when friends introduced me to Jonathan Cook, a British reporter based in the Israeli Arab city of Nazareth. The place of our meeting was the Beit al-Falastini (the Palestinian House), a renovated ancient stone building in the citys old market that during the day serves as a coffeehouse and at night is the nearest thing Nazareth has to a pub. We chatted in the dim surroundings of the cavernous interior, barely able to make out each other in the flickering candlelight. But it soon became clear from our conversation that we shared a concern about the direction Israel is taking. For both of us, this was of more than academic interest: I have adopted this country as my new home, and Jonathan has adopted it through his marriage to Sally Azzam, a native Nazarene.

After our first meeting, Jonathan, ever the inquisitive journalist, arranged to come to Tamra to talk to me again. He published the interview in Britains Guardian newspaper on 27 August 2003, under the headline A Jew Among 25,000 Muslims. That article sparked worldwide interest in my story and brought me to the attention of HarperCollins, who have now encouraged me to publish a much fuller account of my journey from one side of the ethnic divide to the other. My deepest thanks go to Jonathan, who has been a companion on that journey, helping a novice author give expression to her thoughts, experiences and impressions. Without his guidance, I have no doubt this would have been a poorer book. But most of all I want to thank Jonathan for his dedication to reporting the truth and his unwavering commitment to creating a more just and humane society in Israel.

My thanks also go to Sally Azzam Cook, for her patience, suggestions and help to Jonathan; Dr. Asad Ghanem, head of politics at Haifa University, and his wife, Ahlam, for opening their home to me and helping to change the course of my life by teaching me about the reality of theirs; Dr. Uri Davis, for his steadfast friendship and sound advice on a wide variety of subjects and his enormous contribution towards explaining the essence of the conflict; Rabbi Dr. John D. Rayner, for his support and enthusiasm regarding my move to Tamra; Dr. Afif Safieh, the Palestinian delegate to the United Kingdom and the Holy See, for his support, guidance and encouragement; Dr. Mahdi Abdul Hadi, head of the Palestinian Academic Society for the Study of International Affairs (PASSIA), East Jerusalem, for his friendship and support and the use of his wonderful library; Dr. Daphna Golan, director of the Minerva Centre for Human Rights, Hebrew University of Jerusalem, for her friendship, shared concerns and time; Dr. Adel Manna, of the Van Leer Institute, Jerusalem, whose phone call of support was deeply appreciated, for his historical input; Dr. Said Zidanem, associate professor at Al-Quds University, East Jerusalem, for enlightening conversations held in his familys home in Tamra and for his continuing support of my endeavours; Amin Sahli, Tamras city engineer, for teaching me the difficulties of planning in a town without land; Eitan Bronstein of Zochrot, for his shared vision of what life could be in Israel and for his courage; Harry Finkbeiner of Kibbutz Harduf, for help with research; the Gaza Community Mental Health Care project, for their guidance of and support for my work for Mahapach, and for their generous invitation to visit Gaza to learn from them; Wehbe Badarni of Sawt al-Amal (Voice of the Labourer) in Nazareth, for teaching me about employment discrimination and for his devotion to his work; Abdullah Barakat, assistant to the governor of Jenin, for helping me meet the people of Jenin; Mayor Adel Abu Hayja and the Municipality of Tamra, for welcoming me into their community; Richard Johnson, my editor, for his determination to see my story in print and for his continuous encouragement; Dr. Carlos Lesmes, anaesthetist, for his ongoing help and support with pain control and his interest in the book. My deepest thanks go to Nan Talese and Doubleday for their belief and constant support of my endeavours and their determination to publish this book. Dr. Oded Schoenberg for his patience and compassion, and the rest of the team at the Herziliya Medical Centre who have been on my case for the last five years; Arlette Calderon, Dr. Nissim Ohana, Dr. Daniel Kern, and Avi Millstein; Professor Yaacov Peer and the Department of Ophthalmology at Hadassah Hospital, Jerusalem, without whom I would never have got this far; Mahapach, for their unique contribution to Israeli society; and my friends, too numerous to mention individually. Special thanks go to my family in Tamra, for their trust in me and for the remarkable way in which they absorbed me into their circle.

Finally, I have changed the names of some people who appear in the book, including my family in Tamra, for reasons of confidentiality and safety.

Susan Nathan

Tamra, Israel

December 2004

THE ROAD TO TAMRA

The road to the other side of Israel is not signposted. It is a place you rarely read about in your newspapers or hear about from your television sets. It is all but invisible to most Israelis. In the Galilee, Israels most northerly region, the green signs dotted all over the highways point out the direction of Haifa, Acre and Karmiel, all large Jewish towns, and even much smaller Jewish communities like Shlomi and Misgav. But as my taxi driver, Shaher, and I look for Tamra, we find no signsor none until we are heading downhill, racing the other traffic along a stretch of dual carriageway. By a turn-off next to a large metal shack selling fruit and vegetables is a white sign pointing rightwards to Tamra, forcing us to make a dangerous last-minute lane change to exit from the main road. Before us, stretching into the distance, is a half-made road, and at the end of it a pale grey mass of concrete squats within a shallow hollow in the rugged Galilean hills. Shaher looks genuinely startled. My God, its Tulkaram! he exclaims, referring to a Palestinian town and refugee camp notorious among Israelis as a hotbed of terrorism.

A few weeks earlier, in November 2002, I had run the removals company in Tel Aviv to warn them well in advance of my move to Tamra, a town of substantial size by Israeli standards, close to the Mediterranean coast between the modern industrial port of Haifa and the ancient Crusader port of Acre. Unlike the communities I had seen well signposted in the Galilee, Tamra is not Jewish; it is an Arab town that is home to twenty-five thousand Muslims. A fact almost unknown outside Israel is that the Jewish state includes a large minority of one million Palestinians who have Israeli citizenship. Making up a fifth of the population, they are popularly, and not a little disparagingly, known as Israeli Arabs. For a Jew to choose to live among them is unheard of. In fact, it is more than that: it is inconceivable.

Next page