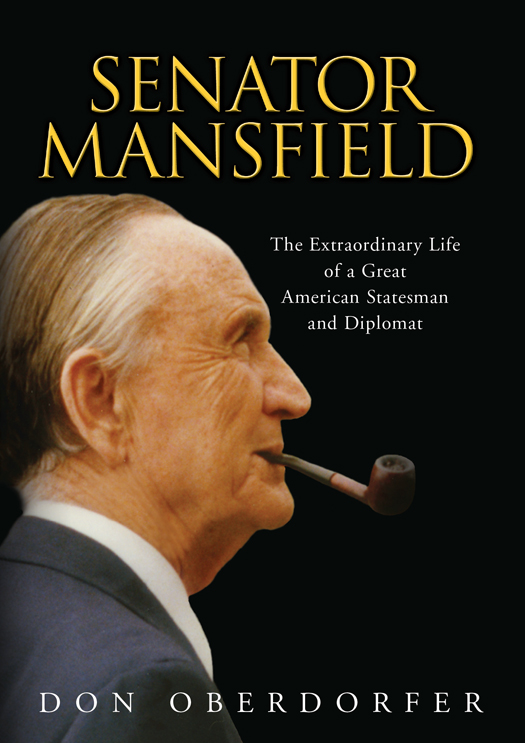

2003 by Don Oberdorfer

All rights reserved

Copy editor: Joanne S. Ainsworth

Production editors: Duke Johns and Robert A. Poarch

Designer: Janice Wheeler

Compositor: Brian Barth

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

Oberdorfer, Don.

Senator Mansfield : the extraordinary life of a great statesman and diplomat / Don Oberdorfer.

p. cm.

Includes bibliographical referernces.

ISBN 1-58834-166-6 (alk. paper)

eBook ISBN 978-1-58834-514-1

1. Mansfield, Mike, 1903. 2. LegislatorsUnited StatesBiography. 3. United States. Congress. SenateBiography. 4. StatesmanUnited StatesBiography. 5. DiplotmatsUnited StatesBiography. 6. United StatesPolitics and government19451989. 7. United StatesForeign relations20th century. I. Title.

E840.8.M2O24 2003

328.73092dc21

[B]

2003045553

British Library Cataloguing-in-Publication Data available

The paper used in this publication meets the minimum requirements of the American National Standard for Information SciencesPermanence of Paper for Printed Library Materials ANSI Z39.48-1984.

The paper used in this publication meets the minimum requirements of the American National Standard for Information SciencesPermanence of Paper for Printed Library Materials ANSI Z39.48-1984.

This book may be purchased for education, business, or sales promotional use. For information please write: Special Markets Department, Smithsonian Books, P.O Box 37012, MRC 513, Washington, DC 20013

For permission to reproduce illustrations appearing in this book, please correspond directly with the owners of the works, as listed in the individual captions. Smithsonian Books does not retain reproduction rights for these illustrations individually, or maintain a file of addresses for photo sources.

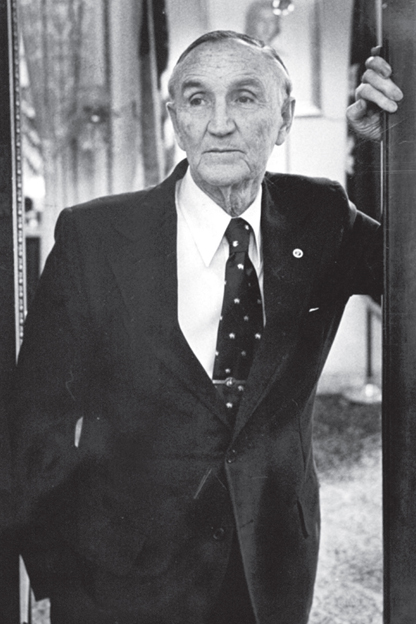

Frontispiece: Mike Mansfield as Majority Leader of a very different Senate: he broke all records for longevity in office and for the respect and affection of his colleagues. Photo by James K.W. Atherton, The Washington Post.

www.SmithsonianBooks.com.

v3.1

CONTENTS

PREFACE

For most of his ninety-eight years, Mike Mansfield did not want this book to be written. Asked by journalists how he would like to be remembered, he responded, When Im gone, I want to be forgotten, and he may actually have meant it. Although he was among the most visible and most admired figures of twentieth-century American politics and diplomacy, he was a man of genuine humility who rejected all pretension and claims to greatnesswhich, in the view of all who knew him, made him all the greater. Serving with great distinction as Majority Leader of the U.S. Senate during the administrations of Presidents John F. Kennedy, Lyndon B. Johnson, Richard M. Nixon, and Gerald R. Ford and as a renowned U.S. ambassador under Presidents Jimmy Carter and Ronald Reagan, he consistently rejected all suggestions that he write his memoirs or cooperate with an oral history project or biography of his remarkable life.

I asked him in early 1998 to grant me a series of interviews covering his life and work. Standing tall as always despite his advanced years, fingering his beloved briar pipe filled with the common mans Prince Albert tobacco, he fixed me with his keen and level gaze and rejected my request out of hand, saying he had neither time to devote to such a project nor interest in it. But then, surprisingly, he served me a cup of the instant coffee that he always prepared for visitors, sat me down at a plate of cookies, and recounted a fascinating conversation with President Johnson four days before Johnsons weighty 1968 decisions that became the turning point of the U.S. war in Vietnam. Later I discovered that Johnson had secretly taped the conversation. Mansfield, delighted at this news, helped me obtain access to the recording, which even now has not been released by the Lyndon B. Johnson Library. The recording demonstrated that Mansfields recollection, thirty years later, was astonishingly accurate.

When I told his close friend, former Senate aide Charles Ferris, that Mansfield had rejected my request for a series of interviews, Ferris advised me, Dont ask him, just do it. I then began what turned out to be a series of thirty-one more meetings with Mansfield over the last three and one-half years of his life. I never again asked, nor did he ever volunteer, permission to proceed with this activity. He certainly knew what I was doing and helped me gain access to documents I could not have obtained on my own, but he never inquired about my work on this project nor asked to see a word I had written. On the one occasion when I inadvertently mentioned the dreaded word biography, he quickly responded, Its unauthorized!

A history major at the University of Montana and later a professor of Asian history, he possessed a historians sense of the importance of events he witnessed, especially in the field of foreign affairs. He wrote personal notes for his files immediately after many of his meetings with presidents and other important officials. He wrote memos, some scrawled on legal pads, of his own ideas and conclusions as they evolved, documenting the changes in his view of the developments of the day. Without setting out to do so, Mike Mansfield left a remarkable record of his extraordinary life and work, especially of his half-century involvement in United States relations with Asia, a vital part of the world he studied more energetically and understood more deeply than any other political figure of his time.

Mansfield had served in the lowest ranks of all three then-existing U.S. military services, the Navy, Army, and Marines, during and shortly after World War I. Having seen military life and action firsthand from those vantage points, he was unusually skeptical of the use of force in international affairs and always in the forefront of those urging political solutions to international ills. Among those with direct and frequent access to the Vietnam War presidents from Kennedy to Ford, he was among the most consistent, persistent, and articulate critics of the ill-fated commitment of American troops in Indochina. He understood better than almost anyone else the central role of China, a country that had fascinated him from his brief service there as a Marine in 1922. He played a significant although largely unknown part in Nixons opening to Beijing. But as revealed in tape recordings secretly made by Nixon and recently released by the National Archives, their collaboration on China was not free of the fierce passions and double-dealings that eventually brought Nixon down.

Many histories of international events tend to neglect the important role of Congress. This is due partly to the journalistic and historical focus on the White House and the predominance of presidential power in foreign affairs and partly to the greater availability of the records of the executive branch of government. The story of Mike Mansfield, who amassed and bequeathed probably the most extensive record of substance of any congressional leader in contemporary times, helps to redress that imbalance.

Mansfields work continued during his nearly twelve years as ambassador to Japan under Presidents Carter and Reagan after his retirement from Congress. As ambassador, most of his communications with Washington were in the form of State Department cables, many of which were declassified at my request under the Freedom of Information Act. At the same time, he continued to communicate directly, at times completely outside of normal government channels, with the two presidents he served. The records of those interventions have also been made available.

The paper used in this publication meets the minimum requirements of the American National Standard for Information SciencesPermanence of Paper for Printed Library Materials ANSI Z39.48-1984.

The paper used in this publication meets the minimum requirements of the American National Standard for Information SciencesPermanence of Paper for Printed Library Materials ANSI Z39.48-1984.