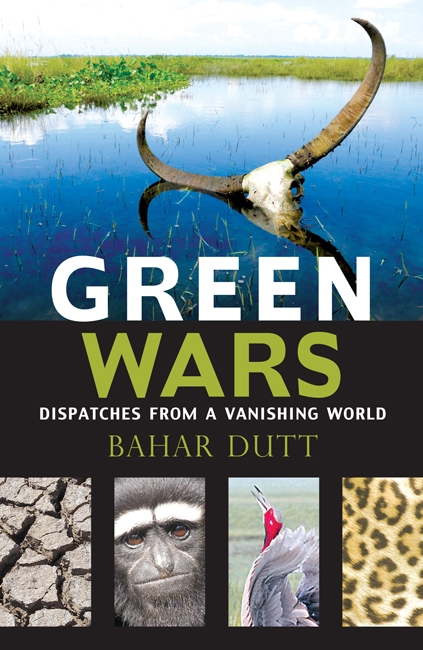

Green Wars

Dispatches from a Vanishing World

BAHAR DUTT

HarperCollins Publishers India

For my dad,

for playing both parents

to two difficult daughters

without a grumble.

And for my mum: we miss you.

Contents

The word environmentalism evokes extreme reactions in people depending on which side of the debate one is on. The editor of a leading media house, everytime I pitched a green story, would invariably complain, environmentalism is stalling growth; all I am interested in is double-digit growth for this country. Its a common reaction, shared by many urban, educated Indians, that development at breakneck speed will get our country out of its current misery. They believe that first we need development, environment protection can come later. Their belief system is based on the EKC (Environment Kuznets Curve) hypothesis, which suggests that environmental effects are initially low at low levels of economic growth. At higher levels of economic development, countries are able, through structural changes, to adopt industrial and agricultural technologies that are less harmful to the environment. The editor quoted believes the same: that first we need development and then we will have the money to clean up our rivers or plant more trees to increase our green cover. However, the experience of the developed world has shown it isnt always as simple as that. In fact, the EKC theory is now widely contested. Look at the growth story of China. It is hailed by economists round the world, yet with no mention of the high levels of pollution, the loss of species, the contamination of its rivers or high incidence of respiratory diseases.

Even with Indias growth story, successive governments have led us to believe the same: that as we soar towards a developed world, we will have more money to clean our rivers and seas, more funds to give for tiger protection or to deal with the issue of declining species. We know now from the experience of other developed nations like the US that the EKC hypothesis doesnt work, particularly in the context of biodiversity loss. Increasing only the GDP levels or per capita incomes, in fact, can increase pollution and CO2 emissions in the long run. Many environmental problems, especially deforestation and loss of species, have been created and exacerbated by economic growth. Extinct species cannot be resurrected; once gone, they are lost forever, no matter how much money is spent.

For the first ten years of my career, I ran a community-based conservation project with the belief that we could work with local people on the ground to save wildlife, to make a real difference. I was so busy working in villages on my conservation project that I lost sight of the big picture. What I missed was that in that same decade, India had arrived as a superpower and soon there were huge economic super stressors out there eating, away our forests and wilderness areas. This book encapsulates the story of my transition from a conservation biologist to a journalist, of my travels around India and abroad, reporting from pristine rainforests, rivers and mountains, struggling with this constant internal debate: how can our biodiversity and wilderness areas be preserved from this hungry giant called development?

This book is not meant to be a diatribe against capitalism or modern living. I am not urging you to go back to living in huts or travel by horse-driven carriages. What this book seeks to explore is the tension between environment and development and to question the existing model of growth at any cost that has led to an unprecedented onslaught on Indias forests and rivers. It seeks to put you, the reader, at the centre of some of these choices we make. Of course, growth is necessary. We need roads, we need sources of energy, but perhaps we need to start questioning: how much is too much and what is the tipping point?

Much of contemporary writing in India has looked at the impact of this unbridled development without breaks model on our urban and rural landscapes and what this has done, for instance, to human beings and to traditional societies. Not much writing has focused on the impact of development on our natural environment and our most precious wilderness spaces. Scientist Jared Diamond states that there are four main causes of extinction of wild species, which he refers to as the Evil Quartet of Extinction in which habitat destruction is a central cause. Even in the popular media, we focus on just one cause that Diamond lists, i.e., poaching. The destruction of habitats is largely ignored, rarely making it to news headlines.

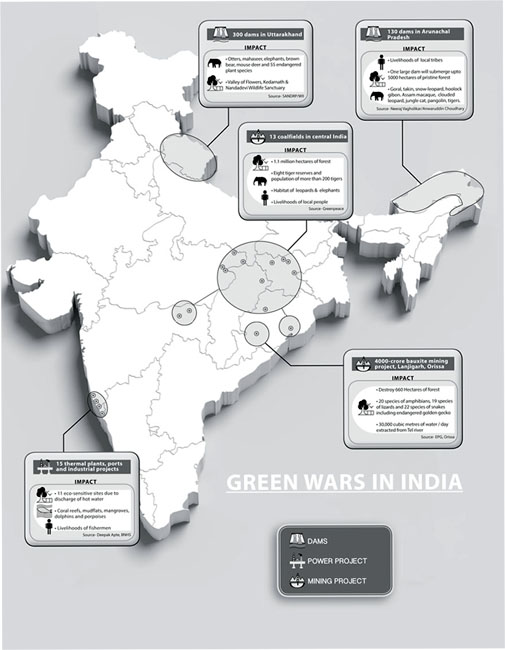

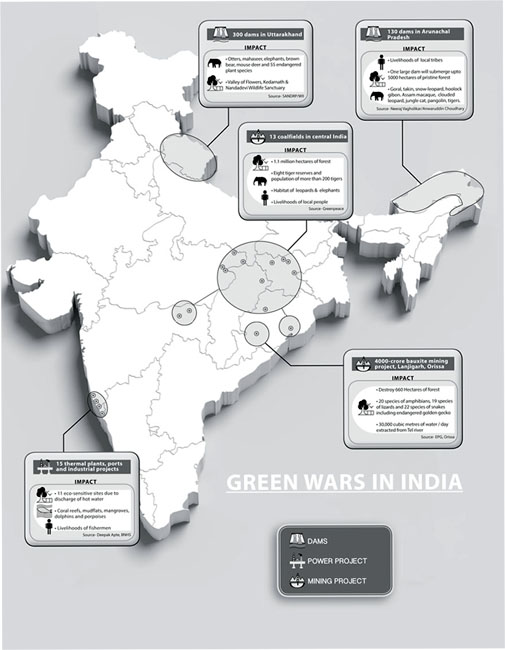

Let me illustrate this with real examples. In north India, the entire Upper Gangetic Basin has been earmarked for over 300 small and big hydropower dams. Once these dams are constructed almost 70 per cent of the Ganga and its tributaries will flow through tunnels, submerging large swathes of rich Himalayan forests. The entire northeastern region of the country, home to some of our richest biodiversity, is slated to be the power house of the country for production of over 50,000 MW of energy. Neeraj Vagholikar, who works with Kalpavriksh, a Non-Governmental Organization (NGO), has spent the last decade documenting the impact of large dams on northeast India. He estimates that over 130 mega dams along with 900 micro and mini hydel projects, once constructed, will cover every inch of the rivers of the region. In of this book I deal with the struggle of an indigenous tribe against a dam, and a prime minister who rushes to lay the foundation stone even though the environment clearance process is not through.

Marine biologist Deepak Apte from the Bombay Natural History Society has estimated that along Indias western coast, at least fifteen coal-fired power projects equalling 25 GW of power are proposed to be built on a narrow strip of coastal land, 50 to 90 km wide and 200 km long. This represents a 200 per cent increase in coal-fired power for the entire state of Maharashtra. In the process, at least eleven eco-sensitive sites will be severely damaged from the discharge of hot water from the power plants into the sea, not to mention the economic loss to local fishermen. Combined with other projects like shipyards, ports and coastal mining, this implies there would be big infrastructure projects every 2025 km along the Konkan coast. This in the same area that was declared an eco-sensitive zone in 1997 and is home to rich coastal and marine biodiversity associated with coral reefs, mudflats and mangroves. Moving further south, from Konkan, environment lawyer Ritwick Dutta estimates that over 182 large dams, power plants and chemical treatment plants will be set up in the biodiversity hotspot of the Western Ghats, just recognized by the UN as a World Heritage Site, home to over 5,000 species of plants and 100 species of mammals, with many new species yet to be discovered.

Now take a look at the impact of this model of development on Indias forests. Since 1980, over 1.5 lakh hectares of forest land have been diverted for the cause of Indias development, 50 per cent of that figure in the last ten years. Take a look at the list of projects that came for approval to the National Board of Wildlife, Government of India, in the year 2010, celebrated as the International Year of Biodiversity across the globe:

- A limestone mining plant on the boundary of the Rajiv Gandhi Wildlife Sanctuary in Andhra Pradesh, one of the finest habitats for the tiger;

Next page