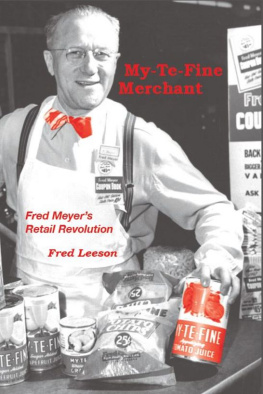

MY-TE-FINE MERCHANT

Fred Meyers Retail Revolution

Fred Leeson

Smashwords edition, copyright 2014

My-Te-Fine Merchant

Fred Leeson

Copyright Fred Leeson 2014

Published by Irvington Press at Smashwords

ISBN 978-0-9960626-0-2

Library of Congress Control Number: 2014905872

In honor of those who worked with, endured andrespected Fred G. Meyer, a brilliant and difficult man

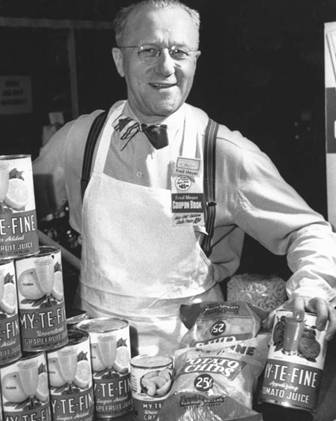

ON THE COVER

Fred Meyer spent little time during his longcareer personally waiting on customers. Yet he chose the imagery ofthe grocers apron when he posed for this publicity photo in 1947,the start of his post-war boom. Meyer was 61 at the time. (OregonHistorical Society Fred Meyer Collection, Box 7)

Contents

Behind the BowTie

An elderly man with a hat pulled low on hishead and using a cane to steady his weakened right leg foundhimself confronted on Southwest First Avenue near Harrison Streetin Portland by a young man with long hair and a bedroll strapped tohis back. The young man asked for money.

The man with the cane paused. Nearly 70 yearsearlier, he, too, had been at a similar point in life footloose,with little money in his pockets and no firm destination in mind.Young and headstrong, he had set out across the country in searchof adventure and his own place in the world. Ultimately, after anunsuccessful attempt at getting rich quick, he settled down nearlyas far as possible from the New York City neighborhood he fled as ateenager. On the streets of downtown Portland, the old man hadbuilt a career over several decades that made him wealthy beyondhis dreams and transformed the way shoppers in the PacificNorthwest bought groceries, clothes, drugs and a wide variety ofother goods.

The young man had no idea that the old mansname glowed in big red electrified letters over more than fivedozen one-stop shopping centers in four states, or that the man inhis late 80s possessed a net worth ranging well into tens ofmillions of dollars. The frail mans route to success had not beendirect or speedy; it was a combination of happenstance,intelligence, perseverance and a domineering personality thatpushed others to their limits in attempting to earn his praise.

Yet the man who could berate his managers inclosed-door meetings for hours at a time seldom showed that side ofhis personality outside his office. He enjoyed talking to customersin the stores that bore his name. He liked conversation to besimple and direct. Big words, he believed, were a hindrance tocommunication. He was endlessly curious about what his customerswanted, how best to serve them and means of cutting costs. Heshowed the same patience and curiosity as he engaged in a briefconversation with the young man seeking money.

Wealthy as he was, the old man had nevershown much of a charitable streak. He was in the process offiguring out how to leave his tens of millions in trust for thepublic benefit, but hed never been keen about giving away moneywhile he was alive. Now in his late 80s, he was still busy runninghis big company. His idea of helping people was providing jobs, nothandouts. He liked giving underdogs a chance and seeing if theywere willing to work hard and make something of themselves. Thoughruthlessly shrewd in business, the old man seemed to have anunderstanding about human frailty; he showed remarkable patience attimes with employees suffering from substance abuse or withbusiness tenants who struggled with bookkeeping or managerialproblems.

Yet the old mans endless drive for wealthwas not for his own earthly pleasure. He lived a simple life. Hisapartment was sparsely furnished. His closet was mostly empty. Hespent almost nothing on personal recreation and seldom socializedwith his few friends who knew him well. He believed that manysuccessful entrepreneurs succumbed to infatuation with their ownegos and wasted money that could be better spent building theirbusinesses. He had tasted failure more than once in his own lifeand had seen others successful businesses fail along the way. Trueto his simple lifestyle, the old man seldom carried more than $20in cash with him.

Something in the young mans plea for help who knows what it was struck a nerve in the old man. When heopened his wallet that day it contained three one-dollar bills. Hehanded over all three and waited for the young man to walkaway.

Meyer topped his banquet regalia withhis signature bow tie. It was a clip-on. The man who often workedseven days a week and whose commercial empire had been built onefficiency and standardization no longer wasted time tying clothstrips around his collar.

Of course, Meyer had been the center ofattention on several other occasions, notably store openings whenhed greet the anonymous customers to whom his retail career hadbeen devoted. Often he would help serve a huge cake weighinghundreds of pounds and engage in friendly chitchat with customerswho were thrilled to shake his hand. At Christmas, Meyer oftenwould be pictured in the newspapers giving away tons of food andtoys to the Salvation Army and the Sunshine Division of thePortland Police Bureau, his two preferred charities. He didnt givecash; always thinking of savings and business first, the food andtoys were wholesale and often items that werent moving quickly offhis store shelves.

Others who joined in the praiseincluded: Mayor Neil Goldschmidt, then perhaps at the height of hispolitical popularity; former Gov. Tom McCall, and Meyershand-picked successor to lead Fred Meyer Inc. after Meyers death,Oran B. Robertson.

Robertson and anyone else who had worked closely with Meyer knewthat the first part of the sentence was true. The second part wasthe punch line. Meyer might look in public like a quiet oldrelative at a wedding with his wire-rimmed glasses and bow tie, butin the executive offices and board room at Fred Meyer Inc. he wasstill the dominating tiger who commanded respect and intimidatedlesser minds into silence.

Just a few years before, he had fendedoff what he interpreted as an internal coup by executives andcorporate directors who thought he was too old to be running amajor public corporation and who wanted him to step down. But theyunderestimated him. Meyer won that battle behind closed doors andthe challengers departed quietly, leaving behind few public hintsof the rancor. Soon thereafter, Meyer suffered a stroke that wouldhave crippled most people. His doctor told him hed never walk orwork again, but in three weeks Meyer was back at the office,walking with a cane and struggling to get his signature back toreadable form for corporate documents.

In the time he had left, Meyer was trying tocraft a management team that would succeed him and was making plansfor his estate that would amount of tens of millions of dollars anumber that Meyer himself could not quantify during his life. Heowned nearly 30 percent of the stock in Fred Meyer Inc., but howmuch his stake was worth depended on what a willing buyer wouldpay, and that likely would depend on whether a buyer wanted theentire company or just part of it. In his later years, he hadreceived offers from time to time to buy Fred Meyer Inc. He wouldlisten patiently, and then always say no thanks. Meyer in 1976couldnt know that his management team would fracture not longafter his death, and that his best-laid plans would generatelawsuits involving several of the states top legal minds fornearly a decade.

Of course, there was other Portland news onthat February Friday. State and federal regulators had issued newobstacles to Portland General Electric Co., which was planning tobuild a natural-gas-fired power plant in Northwest Portland and twonuclear plants in Eastern Oregon, none of which was ever erected.In Seattle the same night, Portlands entry in the NationalBasketball Association won its seventh straight game, the longeststreak in the teams six-year history. Bill Walton, an impressiveyoung center with injury-plagued feet, was starting to show thedominance that would help carry the team to a surprising leaguechampionship the following year.