Satyajit Rays Ravi Shankar

An Unfilmed Visual Script

Edited by Sandip Ray

in association with

Dhritiman Chaterji, Arup K. De, Deepak Mukerjee, Debasis Mukhopadhyay

Introduction by Sankarlal Bhattacharjee

CONTENTS

I was born in a house in Lake Avenue, Kolkata, in 1953, and lived there till 1959. Ravi Shankar-ji came there quite a few times to see my father, Satyajit Ray. But I do not have any recollection of those meetings. It was in 1959 that Ravi-ji and Baba worked together for the last time on a film (Apur Sansar). Then we moved to another house in Lake Temple Road and thence to yet another in Bishop Lefroy Road where Baba lived from 1970 till 1992. Ravi-ji was already a busy musician when Baba requested him to compose the background score for Pather Panchali, his debut film. After that he did the music for Aparajito, Paras Pathar and Apur Sansar. They never worked together thereafter because Baba began to compose music for his own films in 1961. But their relations remained as close and congenial as before. Their friendship was based on mutual admiration which lasted till Baba breathed his last. How deeply Ravi-ji was affected by Babas passing could be gauged by the fact that he immediately paid him a soulful tribute through his Farewell, My Friend. The album was released at the Grand Hotel in Kolkata and we attended the launch.

Ravi-ji was a quintessential Bengali bhadralok though he led a cosmopolitan life most of the time. He lived abroad for long periods of time and became a globetrotter. But, strangely enough, he never gave up his Bengali lifestyle. His love for the Bengali language, culture and food was proverbial. Whenever he came to Kolkata for recitals, he tried to manage time to see Baba despite his tight schedules. Cholun mashai, ektu adda mara jaak (Lets meet and have a chat), he would say. And they talked about nearly everything under the sun, in chaste Bengali, during those adda sessions.

Ravi-jis worldwide fame as a sitar maestro obscured his vocal talents. He presented Baba with an LP record where he explained various Indian ragas and raginis. It was meant primarily for a foreign audience. He sang a Holi song there which impressed Baba very much. Incidentally, many classical musicians were good vocalists as well. Ustad Vilayat Khan Sahib was one of them. He sang the song to which Roshan Kumari gave her dance performance in Jalsaghar.

We went to Benares to shoot for Jai Baba Felunath in the winter of 1977. Ravi-ji was then in Benares too. As soon as he came to know about us, he invited Baba to his place and insisted he come along with all his actors and unit people. Ravi-jis nephew Ananda Shankar and his wife Tanushree were then staying with him. We went there along with Soumitra Chatterjee and Santosh Datta. We spent a whole day in the company of Ravi-ji. He showed us round a large plot of land adjacent to his house saying that he had decided to set up his music academy on that spot. It has always been my ambition to have my own teaching institution in India, he said.

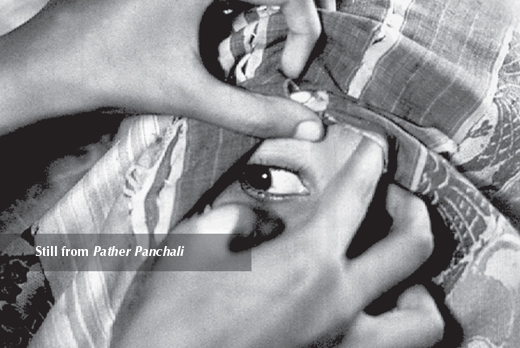

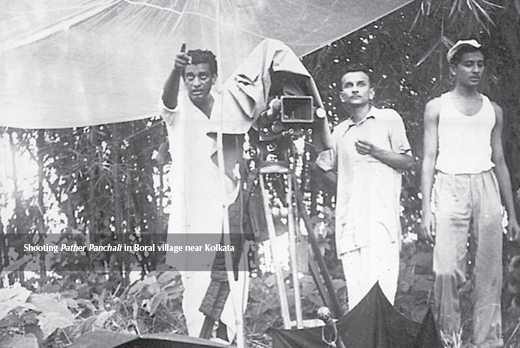

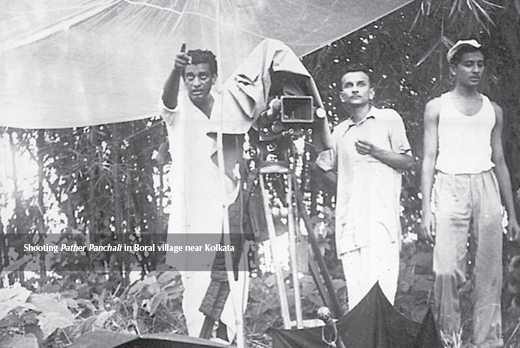

Those who know well about my fathers work know that Baba made a storyboard for a short film on Ravi-ji in the early phase of his career as a film-maker, though it is not yet conclusively known exactly when he did so. Nor is it known why it did not turn into a film. According to Marie Seton, Babas biographer, the storyboard was made in 1951. But there are film scholars who argue against this date. Whatever the date may have been, it may not be unreasonable to say that the storyboard was made before the time of Aparajito. For Baba left drawing blocks and used red notebooks (kheror khata) for the first time to write the screenplay for his second feature film.

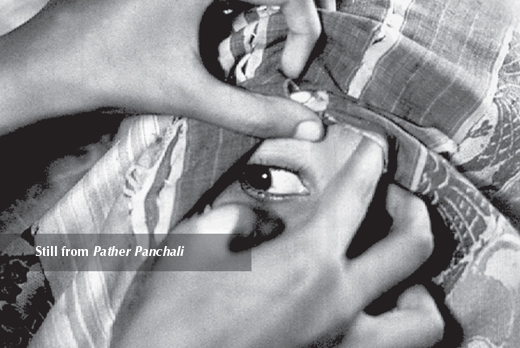

The storyboard on Ravi Shankar-ji was a visual one, full of sketches drawn in the very manner of that for Pather Panchali. The 32-page drawing book, containing over a hundred sketches and some technical instructions on camera movements and other things, has been carefully preserved in the archives of our Society for a long time.

We decided to send it to print in the hope that a facsimile edition would give the admirers of my father the world over an idea of the format he chose for making his very early films. This is the first time a whole storyboard comprising sketches by my father is going to appear in book form. We are sure it will be a treat for readers.

We owe our thanks to D.N. Ghosh, the president of our Society and a distinguished author himself, and all our members for the unstinted encouragement we have received from them in bringing out this book. We would also like to say Thank You to V.K. Karthika and Shantanu Ray Chaudhuri, publisher and managing editor, respectively, of HarperCollins for collaborating with our Society on a second Ray publication, the first having been Deep Focus: Reflections on Cinema that came out in December 2011.

Sandip Ray

Member-Secretary

Society for the Preservation of

Satyajit Ray Archives

(Formerly Society for the Preservation of

Satyajit Ray Films)

Kolkata

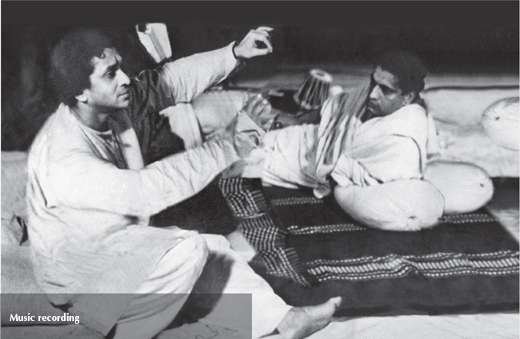

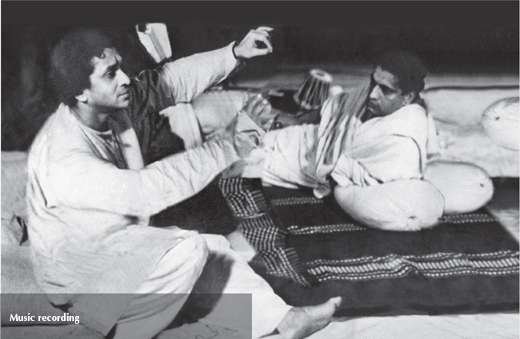

This is the story of a film that did not happen. This is a sitar recital by Ravi Shankar no one chanced to hear. This is one of two unrequited love affairs of Satyajit Ray with the motion picture. A documentary based on a concert, this is an attempt to combine the pleasures of the ear with those of the eye. Like the other film, a fantasy feature titled The Alien, that lies buried in an extraordinarily written screenplay, this too, titled A Sitar Recital by Ravi Shankar, is a script that encompasses a concert from alap to jhala, movement to movement, held only in pictures.

Rays essay Ordeals of the Alien details why The Alien could never be made, but he left no record of why the film on the concert suffered a similar fate. In response to my question on this in 1977, Ravi Shankar said:

You asked about his film on me. Yes, he did have a plan of the kind. Amazingly, he had sketched the whole album on how the movie would go It was probably before he made Aparajito and I was then putting up at Jnanprakash Ghoshs in Calcutta. What I saw in there was: I am playing. The film draws ideas from the melodies and soars into images of trees, storms and springs gradually dissolving the sounds into the images. Then something happened, what really I cannot pinpoint, and the project lay suspended. There has been no further contact on this since.

In her book Satyajit Ray: Portrait of a Director, Marie Seton, however, puts 1951 as the year of the sketches of the documentary. If that is so, they precede the making of Pather Panchali, which again, seems unlikely. In her book, published in 1977, Seton had hoped that the musical short could still be made.

In early 1978, when Ravi Shankars photo-biographer Aloke Mitra went to Ray with his trove of images and requested a cover design, the latter readily agreed and patiently went through the album, stopping now and then to admire a shot or mood. After a long look at a portrait of Ravi Shankar against the backdrop of the Ganga at Benares, Ray had reportedly commented with a sigh, Oh-ho, hes gotten old! When Aloke related this incident to me, I could immediately identify the cause of Rays anxiety: he could see no future for the script on Ravi Shankar.

Next page