Deep Enough for Ivorybills

James Kilgo

with illustrations by the author

Algonquin Books of Chapel Hill

for Jane

Contents

Authors Note

A PROPER SONGFEAST HAS three parts. The first is the event itself, the experience which provides occasion for the singing. My experience has been rich because of the people I have walked with and the paths we have traveled. Like all experience though, it has also been at times both random and ephemeral. In the desire to make sense of it and in some way to keep it, I have tried to sing about it, to tell what happened. That is the bookthe second thing. The third is the giving of gifts. Since, alas, I dont have enough meat and furs to go around, I can only offer instead a full measure of gratitude... to all with whom I have shared a cup of coffee or a warming drink on a cold and windy day; each of them is present here, especially Milton Hopkins, Rick Belser, Grainger McKoy, Bob Benson, Lee Tebo, Jim Meunier, Clark Ivey, and Jeff Carter; to Rob Winthrop and the members of the T. Huntington Abbot Rod and Gun Club, especially Hilburn Hillestad, Ken Ware, Jerry Varnado and the late Don Terry; each of the fourteen others, too numerous to call by name, knows his place at the long pine table; to the three John Kilgosfather, brother, and sonwho got me started and have kept me going; and to four special ladiesmy mother Caroline, my wife Jane, and my daughters Sarah and Ann, who in that order have endured my comings and goings, my odd hours, muddy boots, and scattered gear.

And also to these: Joe Bailey, whose call from Alabama one night was the real beginning of this book; each member of the little writers group that came together at the right time and lasted just long enough; Coleman Barks, poet and friend, who taught me the words; Paul Zimmer, Phil Williams, Mike Nicholson, Judith Cofer, Betsy Cox, and Judson Mitcham, who encouraged me; Stanley Lindberg and Mary Hood, whose faith in the book I could not have done without; Louis Rubin, whose sound judgment made it better; and Marty Carter, who gave up her time and her dining room table for two months to an impatient writer and a word processor.

JAMES KILGO

Athens, Georgia

January 10, 1987

1

Deep Enough for Ivorybills

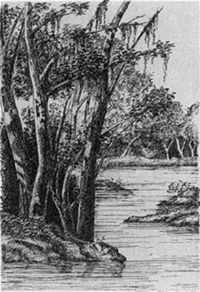

WE USED TO CROSS THE Big Pee Dee River on our way to the beach each summer. The steep drop into the floodplain always surprised me. For two breathless seconds at sixty miles an hour we seemed to hang on the crest of the hill, high above a wide green floor, reposed in the sun below us. There it is, my father would say, the Pee Dee River Swamp. You get lost in there, theyd never find you. Even as he spoke, we would go hurtling down and then, at the bottom, level out onto the long causeway that shot straight across the swamp like a yardstick.

A gloomy wall of forest crowded the road on either side, but when you hit the bridge you could look for a long way up and down the wide, sunny reaches of the river. Here and there a cypress tree, streaming Spanish moss, lifted its crown above the other trees, and sometimes youd see a hawk wheeling in the sun. I bet therere still ivorybills in there, my father would say.

Really? I asked.

Could be. Therere places in that swamp nobodys ever been in.

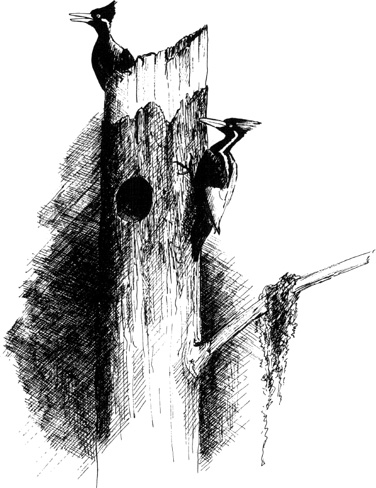

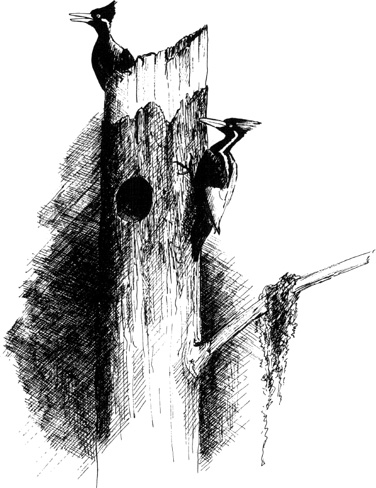

There was just a chance that he was right. Before the extensive logging operations of the late nineteenth century, the floodplains of the great southeastern rivers were prime habitat for this largest and most striking of North American woodpeckers. The ivorybill was uncommon even then, but those who ventured into the deep woods, such men as Audubon and William Bartram, had no trouble distinguishing it from the similar but smaller pileated woodpecker. The plumage of the ivorybill was a glossy blue-black, its prominent beak the color of ivory, and flying from tree to tree it called in what Audubon described as the plaintive tone of a clarinet. By 1941, when I was born, the survival of the species was in doubt. As a child I feared I would never see one, even if I were to spend my life hunting for it, but my fathers observation suggested the possibility.

We lived in Darlington, ten miles west of the river. With no one to take me into the swamp I had to settle for the little creek below my house. I never saw even a pileated woodpecker in its woods, but the stream was deep enough for fishing, and it flowed through a cypress bottom. Our side of it was practically my front yard. On summer nights I would sit in the porch swing with my father and ask him what wild animals lived in those woods. He would say, Ssh. Lets see if we can hear an owl. But after a while he would tell me quietly about fishing in the creek when he was a boy and running barefoot down the same paths I knew to the same swimming holes. And I would ease into sleep upon the murmur of his talking.

Next morning I would go out and sit on the steps in the cool early light and listen to the songs of birds I couldnt name. Though my father was dressed for work when he came out, there was always a chance that he would decide at the last minute that he had time to see if the redbreasts were biting. You remember what you did with those poles? he would ask.

Yessir, and Id be up and running.

Better get the hoe too. And see if you can find a can.

There was always the chilly swish of wet broomsedge against my bare legs and sometimes the stinging rake of a briar as we crossed the field toward the creek and went down into that dark cypress bottom. The damp black soil squished between my toes as we dug for bait among the cypress knees. That was almost as much fun as fishingthe suck of the wet clay as you hoed back a clod and spied a thick, blue worm, almost as big around as your little finger, wriggling into the ground.

With three or four nightcrawlers in the can, we came out of the shade upon a wide bend where banked honeysuckle overhung the water and the sun touched the sandy, scalloped bottom. Finding a place to settle, we spent an hour, intent upon our corks as they bobbed against the sweep of the current. At such times I was easily distracted by birds or butterflies or particularly damselfliesan electric-blue needle of an insect with narrow black wings. Sometimes one would alight on the tip of my pole and I would become so absorbed in the slow pulse of its wings that I would forget my cork. Then my father would say, Watch your cork, son. The round yellow bobber, jerked almost out of sight in the dark water, jolted me into action, and one nice redbreast with its dark green back and crimson throat was enough to make me want to fish forever. When my father left for work, I stayed behind, watching as he picked his way through the rich black mud of the bottom.

When I was six or seven I began spending weekends in the country with a friend named Freddie Dargan. Although he and his brothers treated me like a town boy, I loved to go to their house because they lived above a wild stream called Alligator Branch where their father and mine had played together when they were boys. Summer and winter we ranged the woods, fishing and swimming in the shallow, tea-colored creek when the weather was warm and hunting coons with a black man named Charlie Ross on cool autumn nights. When the night was unusually cold, down in the forties, say, Charlie built us a fire on a hill above the branch. Then we huddled around the flames as we waited for the dogs to strike. Freddie and his brother knew the voices of their dogs, but only Charlie could name the game they were running.