Contents

Guide

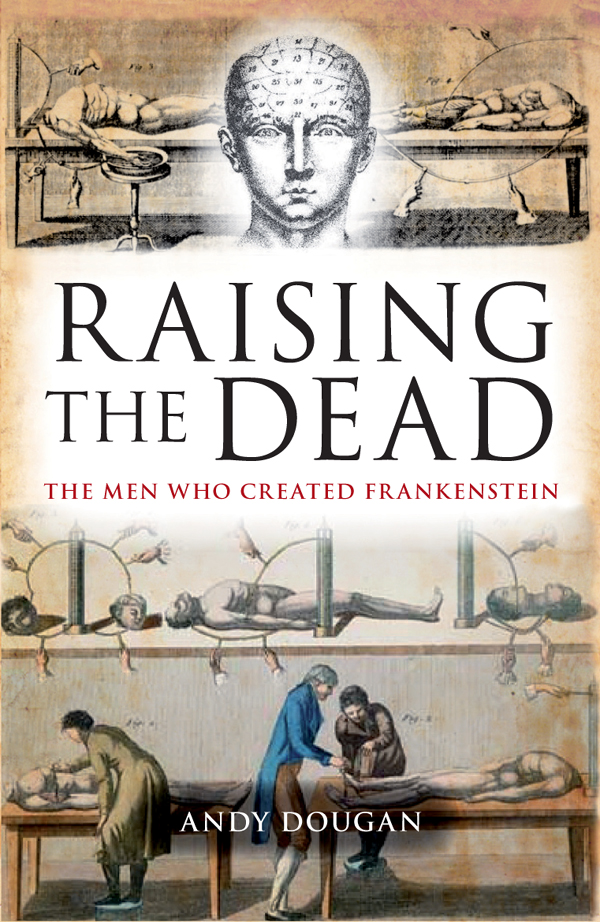

Raising the Dead

Andy Dougan is the author of the Sunday Times best-seller, Dynamo: Defending the Honour of Kiev, which was long-listed for the William Hill Sports Book of the Year. He has also written acclaimed biographies of Robert De Niro, Robin Williams and Martin Scorsese. He lives near Glasgow.

Raising the Dead

The men who created Frankenstein

Andy Dougan

This edition first published in 2017 by

Birlinn Limited

West Newington House

10 Newington Road

Edinburgh EH9 1QS

www.birlinn.co.uk

First published in 2008

Copyright Andy Dougan 2008

The moral right of Andy Dougan to be identified as the author of this work has been asserted by him in accordance with the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act 1988

All rights reserved.

No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored or transmitted in any form without the express written permission of the publisher.

ISBN 978 1 78027 501 7

British-Library Cataloguing-in-Publication Data

A catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library

Typeset by Iolaire Typesetting, Newtonmore

Printed and bound by MBM Print SCS Ltd, Glasgow

For Diane

Contents

List of illustrations

Acknowledgements

Although I did not become aware of it until I began researching, the origins for this book lie with a chance remark made during my childhood by my late grandmother Mary Morrissey, so for that and many other things I am grateful to her. More contemporary thanks go to my agent, Jane Judd, for her support during a long dry spell, Jan Rutherford for her interest and rescuing the project from oblivion and Andrew Simmons at Birlinn.

None of the research would have been possible without the inestimable help of the staff at the Mitchell Library in Glasgow, especially those in Special Collections and the Glasgow City Archive. I am also very grateful for the help of the staff at Glasgow University Library.

My thanks, somewhat belatedly, should also go to the lecturers in the History of Science Department of Glasgow University. I understand the department no longer exists as a separate entity, but who would have thought those lectures from 1975 would pay dividends so far down the road? I would also like to thank Hazel Clement and Joan Self from the Met Office for their efforts on my behalf.

Finally I very much want to acknowledge the research done in this field by Stuart McDonald and his colleagues at Glasgow University and the work done by FLM Pattison on his great-great-great uncles career. These have been enormously helpful in guiding and steering my own research.

Bread has been made (indifferent) from potatoes; And galvanism has set some corpses grinning.

Lord Byron, Don Juan, Canto 1, CXXX

Prologue

Thunder rumbles over a disused windmill on a windswept moor as jagged flashes of lightning illuminate the scene in a dramatic chiaroscuro. The peals of thunder and flashes are nearly simultaneous, meaning the storm is almost overhead. Inside the tumbledown building a scientist frantically checks gauges and throws switches on a complex array of machinery that audibly crackles with electrical force; the crackling intensifies as the storm approaches. The scientist shouts orders to his assistant, a hunchbacked dwarf, but his voice is barely heard above the tempest. Three other people, two men and a woman, look on in mixed fear and horror, cowering for shelter at each crack of thunder. The scientist is concentrating his efforts around a hospital gurney on which lies a giant figure, obviously human, underneath a canvas tarpaulin. Aware that the full force of the storm is about to be unleashed, the scientists movements become more feverish. Gauges are checked and checked again, more switches are thrown and levers pulled as he and his assistant move round the laboratory with renewed vigour. The scientist removes the heavy outer cover and a lighter secondary one, revealing what appears to be the corpse of an extremely tall man. The body, dressed in a black suit and heavy boots, is restrained by large metal hoops around his head, torso and legs. His face is still shrouded by a sheet, and only one large hand, apparently cold and dead, is visible. Finally, the scientist grabs a pulley wheel, and he and his assistant begin to turn it, slowly, with enormous effort, as a series of chains takes the weight and the gurney and the figure on top are raised horizontally towards the ceiling. A recess has been cut into the roof and the gurney fits neatly in exposing the figure to the full fury of the maelstrom overhead. Lightning flashes repeatedly before the scientist decides this has gone on long enough and slowly turns the wheel in the opposite direction to bring the gurney back down to the floor of the lab. He looks on anxiously as it descends. Once the gurney has come to rest, the scientists attention focuses on the figures exposed right hand. Faintly, almost imperceptibly, the fingers start to twitch.

Its moving, its alive! the scientist shouts, barely able to believe it, Its alive, its alive, its alive! His voice rises and falls in hysterical sobs as the anxious onlookers rush in to restrain him.

In the name of God, cries the scientist, now I know what it feels like to be God!

This is how millions of cinemagoers the world over were introduced to the concept of raising the dead; this is the iconic animation scene in James Whales 1931 version of Frankenstein, starring Colin Clive as the scientist and Boris Karloff as his reanimated creature. The film was based on Mary Shelleys novel Frankenstein. Those who saw the film, like those who read the book, were thrilled by this incredible Gothic adventure. Few, however, realised that Mary Shelleys story had a basis in fact. What she imagined as her modern Prometheus was also the serious pursuit of some of the greatest minds of the early nineteenth century, a time when scientists genuinely believed, as Colin Clive did in the film, that they could know what it felt like to be God.

In the winter of 1818, the year in which Mary Shelleys book was published, the sensational story of a strange experiment that had taken place at the University of Glasgow swept through the citys streets, an experiment that was apparently every bit as disturbing as either book or film. Its architect and performer was Andrew Ure, a man who was at the very forefront of scientific knowledge in his day. A man who, like many of his peers, believed that even if his travels took him into dark and unexplored places and set him at odds with the religious establishment, it was a journey he was prepared to make.

1 Let his blood be shed

The chiming of the Tollbooth clock at Glasgow Cross was a frequent and cheering sound for most eighteenth-century Glaswegians. For one thing, when the clock struck one each day it marked the beginning of what was generally regarded as dinner hour, with the city coming to a virtual halt. There was even a time, early in the century, when this was such a welcome announcement that the dinner hour was marked by professional musicians playing traditional Scottish airs on chimes at the Tollbooth Steeple between one and two. This mildly festive arrangement ended when the chimes and the mechanism simply wore out. A new clock replaced the old one in 1816, but, fine timepiece and fitting adornment to Glasgows most famous landmark though it was, the new clock provided no dinnertime gaiety, merely chiming the hours and quarters. As it struck two on 4 November 1818, it was not just the signal for a thriving and growing city to get back to work for Matthew Clydesdale it meant something else entirely. He knew that the sound of the same clock striking the next hour was almost certain to be the last he would hear. He also knew that the sound of the chimes at the hour after that would mean that it wouldnt be long until the beginning of his final journey, a procession through the streets of Glasgow that would bring him to an inevitable meeting with Andrew Ure and James Jeffray. These three men the latter two eminent and respected scientists and Clydesdale a barely literate manual worker could not have come from more different worlds, but their paths were nonetheless destined to cross, and in a way that would enthrall, inspire and disquiet people in equal measure for centuries to come.