Scribe Publications

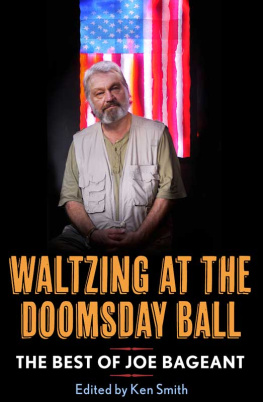

WALTZING AT THE DOOMSDAY BALL

JOE BAGEANT frequently appeared on U.S. National Public Radio and the BBC, and wrote for newspapers and magazines internationally. He was a commentator on the politics of class in America, and his book Deer Hunting with Jesus: dispatches from Americas class war has been adapted for the theatre. He also wrote an online column (www.joebageant.com) that has made him a cult hero among gonzo-journalism junkies and progressives. Joes second book, Rainbow Pie: a redneck memoir , was published in the United States four days after he died in March 2011.

KEN SMITH managed Joe Bageants website from the time it was launched in 2004, and has promoted Joes work widely to his dedicated fans and the wider media ever since.

To working people everywhere

Scribe Publications Pty Ltd

1820 Edward St, Brunswick, Victoria, Australia 3056

Email: info@scribepub.com.au

First published by Scribe 2011

Copyright in individual chapters The Joseph L. Bageant Revocable Intervivos Trust

This selection copyright Scribe Publications 2011

All rights reserved. Without limiting the rights under copyright reserved above, no part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in or introduced into a retrieval system, or transmitted, in any form or by any means (electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording or otherwise) without the prior written permission of the publishers of this book.

National Library of Australia

Cataloguing-in-Publication data

Bageant, Joe.

Waltzing at the Doomsday Ball: the best of Joe Bageant / essays by Joe Bageant; edited by Ken Smith.

9781921844515 (pbk.)

1. Social classesUnited States. 2. Poor whitesUnited StatesSocial conditions. 3. United StatesSocial conditions1980-.

Other Authors/Contributors: Ken Smith (editor)

305.56097309045

www.scribepublications.com.au

Contents

[1]

[2]

[3]

[4]

[5]

[6]

[7]

[8]

[9]

[10]

[11]

[12]

[13]

[14]

[15]

[16]

[17]

[18]

[19]

[20]

[21]

[22]

[23]

[24]

[25]

Introduction

Im so damn average that what I write resonates with people, Joe Bageant once told an interviewer in explaining how he had gained a global following for his essays published on the web. In 2004, at the age of 58, Joe sensed that the Internet could give him editorial freedom. Without gatekeepers, he began writing about what he was really thinking, and then submitted his essays to left-of-center websites.

Joe Bageant died in March 2011, having written two books, and 78 essays that were posted on his own website and also on many other sites. The 25 essays reproduced in this book were first published on the web. Ive selected them based on many emails from readers, web-traffic counts, and specific suggestions from his online colleagues. They appear here as Joe wrote them, apart from copyediting and light corrections agreed to between me and his book editor, Henry Rosenbloom, Scribes founder and publisher.

Joe began writing for various publications in his twenties. He once told me how happy and proud he was when he sold his first article to the Colorado Daily , unashamedly recalling how he got tears in his eyes as he looked at a check for $5. It was only five dollars, but it was proof that he had become a professional writer. Joe freelanced articles for a dozen years, mostly writing about music, but also writing profiles of people such as Hunter S. Thompson, Timothy Leary, and G. Gordon Liddy. With a family to support, Joe found work as a reporter and columnist for small daily newspapers. Then, for two decades, Joe submerged his rage and natural writing style while working at various hard-labor jobs, before working again as a newspaper reporter, and then as an editor of magazines one in military history and before that a magazine that promoted agricultural chemicals.

At the age of 17, Joe enlisted in the U.S. Navy, serving on an aircraft carrier. Joe had farmed with horses for several years, tended bar, and considered himself at times to be a Marxist and a half-assed Buddhist. Always wanting to escape, he embarked on a life-long voyage of discovery that included living in a commune and on an Indian reservation, and, later in life, in Belize and in Mexico.

Joe often said that the Internet allowed him to find his voice. But I would argue that Joe always had his voice, and that what the Internet did for him was to permit him to find a readership. Once his essays started appearing on various websites, Joe soon gained a wide following for his forceful style, his sense of humor, and his willingness to discuss the American white underclass, a taboo topic for the mainstream media. Joe called himself a redneck socialist, and he initially thought most of his readers would be very much like himself working class from the southern section of the U.S.A. So he was pleasantly surprised when emails started filling his inbox. There were indeed many letters from men about Joes age who had also escaped rural poverty. But there were also emails from younger men and women readers, from affluent people who agreed that the political and economic system needed an overhaul, from readers in dozens of countries expressing thanks for an alternative view of American life, from working-class Americans in all parts of the country, and more than a few from elderly women who wrote to Joe to say that they respected and appreciated his writing, but please dont use so much profanity.

The central subject of Joes writing was the class system in the United States, and the tens of millions of whites ignored by coastal liberals in New York, Washington, San Francisco, and Los Angeles. In his online essays and books, and also in conversations over beer or bourbon, Joe would rail against the elite class who looked down on his people poor whites, the underclass, rednecks. Joe was amused that a New York book editor once said to him, Its as if your people were some sort of exotic and foreign culture, as if you were from Yemen or something.

Joe spent almost as much time answering emails as he did writing essays. Often a response to an email would be rewritten and included in his next essay, and Joe would send thanks to the reader for providing the spark. In the six years that Joe was writing for publication on the web, he answered thousands of emails from readers sometimes with just one sentence, but often churning out a thousand words or more.

He and I would talk about the response he was getting to his writing. His explanation was that he was the same as his reader friends, ordinary and fearful. I dont write to them, Joe said in an email to one of his readers. I dont write for them. And I dont write at them. We merely live on the same planet watching the unnerving events around us, things the majority does not seem to see. So I write about that. And maybe for just a moment, a few friends Ive never met do not feel so alone. Nor do I.

I first met Joe only seven years before he died, but it seems as though I had known him all of my life. I learned later that there were many people who had similarly become friends of Joe, meeting first by email, then by phone, and then often making personal visits to his home in Virginia, or Belize, or Mexico.

In 2004, I was living in Nice, France and had read one of Joes essays on CounterPunch.com. I sent him an email praising his style and ideas. He replied with a thank-you note, asking if I were wealthy and why I, an American, was living in France. I explained that I lived frugally in a working-class neighborhood of Nice, eating and shopping where the locals did. That started an email exchange and then many phone calls. In one conversation, he said he was bone tired from a daily three-hour commute to a job he didnt really like. I told him that he should take a couple of weeks off and come to France. He did just that.

Next page