For my girls, Kelly and Abigail Day. You are my world.

Also for Mr and Mrs Day (Simon and Alison). Congratulations, 7 July 2012.

I would like to thank the following people for their help, support, patience and hard work in writing this book. Thank you to Cate Ludlow and The History Press; without whom the book would not have been possible. Also, thank you to my family for their love and tireless support of my work. Further thanks go to my wife Kelly Day (photos) and Tracie Wayling (illustrations), without your brilliant contributions the book would not have been possible either. I would also like to thank Alison White, Mick Cash, Pat Balcombe, Colin Brown, Derek Kelly, Gary Day, the Essex Ghost Hunting Team and the staff of Chelmsford Prison, both past and present.

Big thanks also to the staff of Broomfield Hospital, Maternity and Labour ward, Chelmsford; and the staff of the Royal London Hospital, Constance Green ward. Thanks also go out to Joan at the Sick Childrens Trust, Stevenson House, for all her support over the last year. I should also like to thank those who have been brave enough to come forward with stories of their paranormal encounters in and around the Chelmsford area and have allowed me to share them with you. Special thanks also go to the spirits that have managed to manifest themselves one way or another; this book will let even more people know you are out there. Finally a big thank you to you the reader, I hope you enjoy the book.

Contents

C helmsford is located in the county of Essex, within the London commuter belt, approximately thirty-two miles north-east of Charing Cross, London.

There have been settlements in Chelmsford since ancient times. Evidence of a Neolithic and a late Bronze Age settlement have been found in the Springfield suburb, dating occupancy as far back as 3000 BC .

Later, a Roman fort was built in the area in ad , and a civilian town grew up around it. The town was given the name of Caesaromagus (the market place of Caesar), although the reason for it being given the great honour of bearing the imperial prefix is unclear. Possibly Caesaromagus was a failed planned town provincial capital to replace Londinium or Camulodunum. The remains of a mansio, a combination post office, civic centre and hotel, lie beneath the streets of the modern suburb of Moulsham in Chelmsford, and the ruins of an octagonal temple are located beneath the Odeon roundabout.

An important Anglo-Saxon burial was discovered at Broomfield, to the north of Chelmsford, in the late nineteenth century and the finds are now in the British Museum. The road Saxon Way now marks the site.

The towns current name is derived from Ceolmaers ford which was close to the site of the present High Street stone bridge. In the Domesday Book of 1086 the town was called Celmeresfort and by 1189 it had changed to Chelmsford. By 1199 , the Bishop of London was granted a Royal Charter for Chelmsford to hold a market, marking the origin of the modern town.

Chelmsford became the seat of the local assize during the early thirteenth century (though assizes were also held at Brentwood) and by 1218 was recognised as the county town of Essex; a position it has retained to the present day. Chelmsford was significantly involved in the Peasants Revolt of 1381 , and Richard II moved on to the town after quelling the rebellion in London. The Sleepers and The Shadows , written by the late Hilda Grieve in 1988 using original sources, states:

For nearly a week, from Monday July to Saturday July [ 1381 ], Chelmsford became the seat of government. The King probably lodged at his nearby manor house at Writtle. He was attended by his council, headed by the temporary Chancellor, the new chief justice, and the royal chancery. Their formidable task in Chelmsford was to draft, engross, date, seal and despatch by messengers riding to the farthest corners of the realm, the daily batches of commissions, mandates, letters, orders and proclamations issued by the government not only to speed the process of pacification of the kingdom, but to conduct much ordinary day to day business of the Crown and Government.

Richard II famously revoked the charters which he had made in concession to the peasants on July 1381 , whilst in Chelmsford. It could be said that given this movement of government power, Chelmsford for a few days at least became the capital of England. Many of the ringleaders of the revolt were executed on the gallows at what is now Primrose Hill.

During Tudor times, Henry VIII purchased the Boleyn estate just to the North of Chelmsford. In 1516 , he built Beaulieu Palace on the current site of New Hall School. This later became the residence of his then mistress, and later wife, Ann Boleyn. The palace went on to become the residence of Henrys daughter, by his first marriage; Mary I. During the 1700 s the palace was demolished and rebuilt and in 1798 the English nuns of the Order of the Holy Sepulchre acquired the estate and opened a catholic school there the following year.

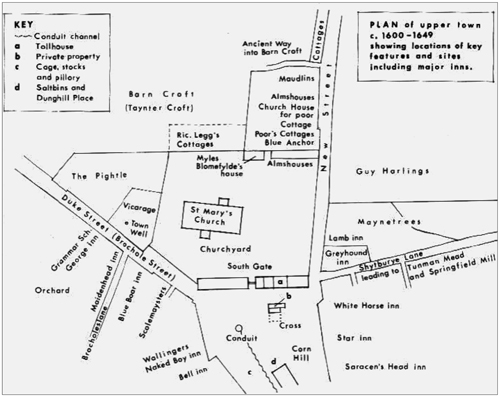

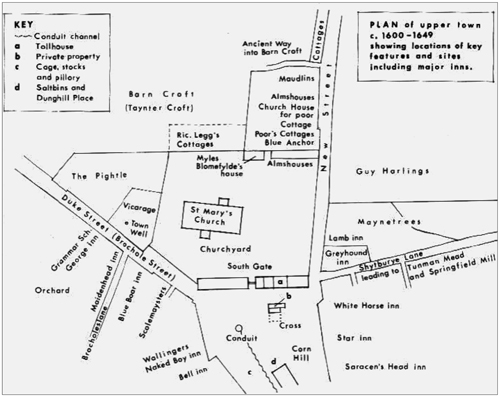

Map of Upper Chelmsford, 16001649.

Another notable period in Chelmsfords history occurred during the Essex Witch Trials of the seventeenth century. Many of the victims of Matthew Hopkins (the self-styled Witchfinder General) spent their last days imprisoned in Chelmsford, before being tried at the Assizes and hanged for witchcraft: several of these executions taking place in the town itself.

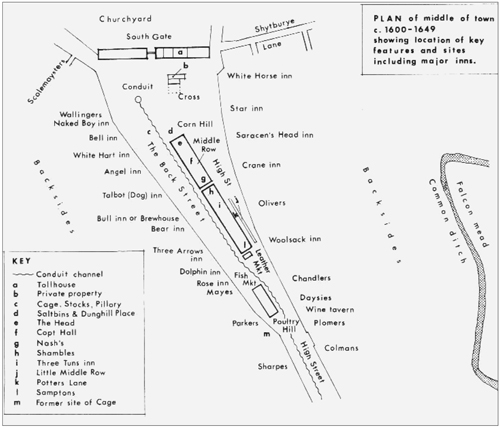

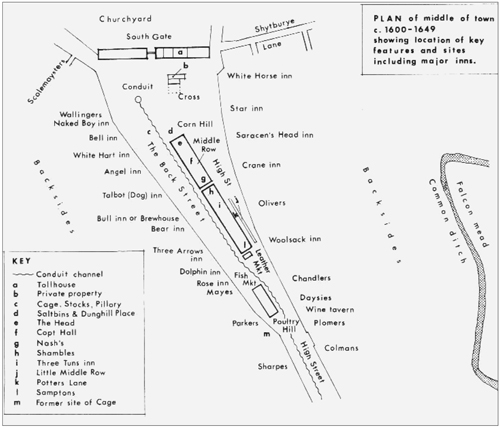

Map of Lower Chelmsford, 16001649.

During the Second World War, Chelmsford, an important centre of light engineering production, was attacked from the air on several occasions, both by aircraft of the Luftwaffe and by missile. The worst single loss of life took place on Tuesday December 1944 , when the th V rocket to hit England fell on a residential street in the town. The bomb hit Henry Road near Hoffmans ball bearing factory and not far from the Marconi Wireless Telegraph Company factory in New Street (which may also have been its intended target). Thirty-nine people were killed and injured (forty-seven seriously). Several dwellings in Henry Road were completely destroyed, and many in nearby streets were badly damaged. A recently restored monument to the dead is in the borough cemetery in Writtle Road.

The GHQ Line was a defence line built in the United Kingdom during the Second World War to contain an expected German invasion. The British Army had abandoned most of its equipment in France after the Dunkirk evacuation. It was therefore decided to build a static system of defensive lines around Britain, all designed to compartmentalise the country and delay the Germans long enough for more mobile forces to counter-attack. Over fifty defensive lines were constructed around Britain, the GHQ Line being the longest and most important, designed to protect London and the industrial heart of Britain. The line ran directly through Chelmsford and along this section the defences were made up of around FW type concrete pillboxes (military bunkers), which were part of the British hardened field defences of the Second World War. Many of these pillboxes are still in existence to the north and south of the town. Faded camouflage paint still remains on old buildings near Waterhouse Lane.

Next page