Published by John Blake Publishing,

an imprint of Bonnier Books UK

4th Floor, Victoria House

Bloomsbury Square

London, WC1B 4DA

Owned by Bonnier Books

Sveavgen 56, Stockholm, Sweden

www.facebook.com/johnblakebooks

twitter.com/jblakebooks

Paperback: 978-1-78946-602-7

Ebook: 978-1-78946-603-4

Audio: 978-1-78946-633-1

All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted in any form or by any means, without the prior permission in writing of the publisher, nor be otherwise circulated in any form of binding or cover other than that in which it is published and without a similar condition including this condition being imposed on the subsequent purchaser. British Library Cataloguing-in-Publication Data.

A catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library.

Design by www.envydesign.co.uk

1 3 5 7 9 10 8 6 4 2

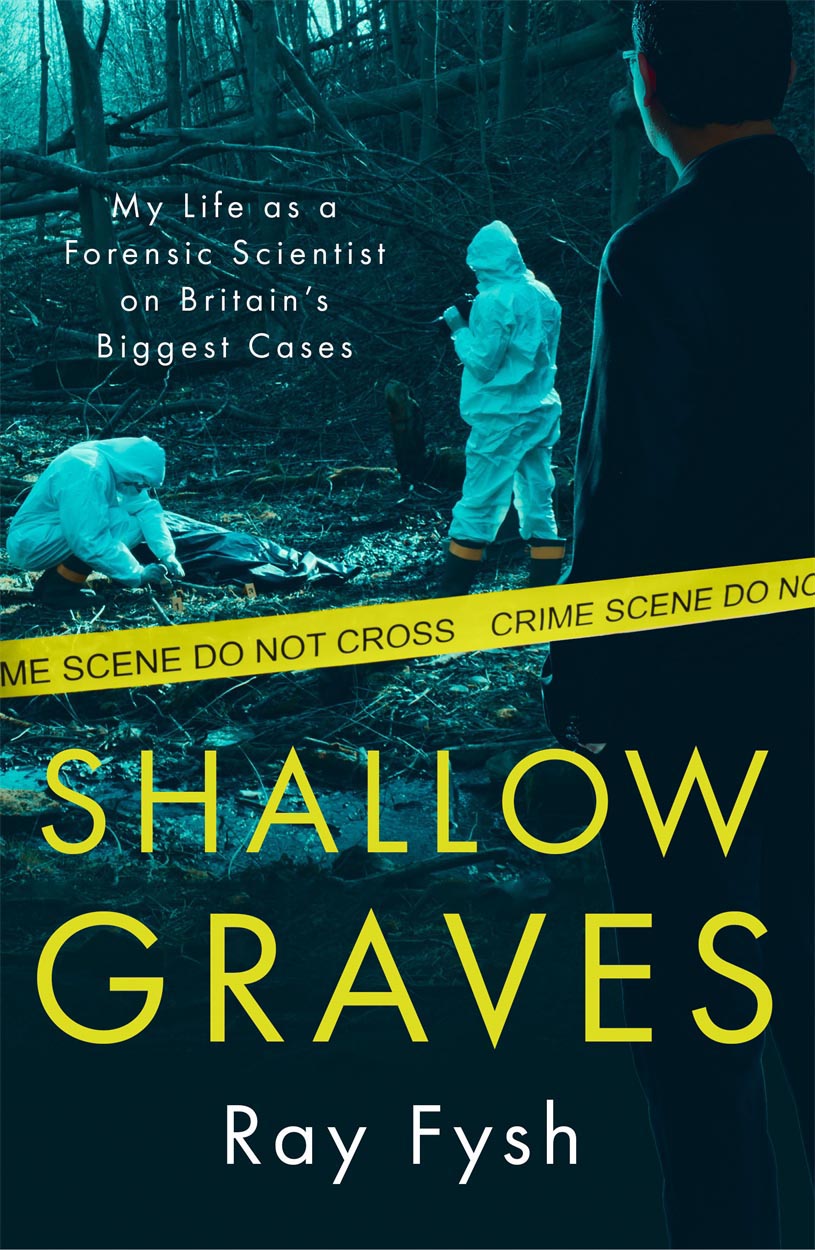

Text copyright Ray Fysh and Jim Nally, 2022

The right of Ray Fysh and Jim Nally to be identified as the authors of this work has been asserted by them in accordance with the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act 1988.

Every reasonable effort has been made to trace copyright-holders of material reproduced in this book, but if any have been inadvertently overlooked the publishers would be glad to hear from them.

John Blake Publishing is

an imprint of Bonnier Books UK

www.bonnierbooks.co.uk

To my late mother and father, Beryl Fysh and Reuben Fysh

CONTENTS

FOREWORD

BY ANDR BAKER

The greatest honour of any detective is to investigate the death of another human being.

In an era when the police are being challenged in their methodologies and processes, forensic evidence so often proves key.

Some forensic evidence is very difficult to question: if DNA testing says theres a one-in-500-million chance of a single sample belonging to a suspect, this along with other details amounts to a fact. Whereas other pieces of evidence, such as blood splatter, require careful interpretation and analysis before they can be used or even prove helpful to a case.

That makes an experienced forensics specialist essential to police investigations.

Ive known Ray Fysh since he was a toxicologist, then as a specialist advisor working with enquiry teams in all areas of forensic evidence gathering. I count Ray as a dear friend, and we often catch up with other colleagues over a beer, reminiscing over old cases, putting them right and challenging one another as to what would you do...

Over forty years, Rays dedication and service to forensics has been invaluable. He has contributed to the development and enhancement of forensic science and is a true stalwart of his profession. Ive counted on his expertise many times throughout my career, but several occasions and cases spring to mind.

The first was at the turn of the millennium. London was recording around two hundred murders per year one-quarter of the national annual numbers. The Metropolitan Police Service (MPS) was also under increased scrutiny, following the handling of the investigation into the murder of Stephen Lawrence in south London. The spotlight was on policing in general and on the MPS in particular: we had to do things better, in a more open way and to much higher standards. We needed to attain better detection rates, to work more closely with families and communities and, of course, to reduce the number of victims of murder.

The MPS took on the challenge with a Murder Prevention Programme, which I oversaw as the Services first Head of Homicide Investigations at Scotland Yard. The idea was to identify and tackle key incidents and acts of violence which, if left unaddressed, could escalate to murder.

A senior analyst, along with a team of six newly recruited, high-potential graduates and a couple of police officers, broke down murders into sixteen strands including domestic violence, knife crime and ritual and worked on finding ways to stop that violence.

A key part of the teams intelligence came from forensics work. While the painting of a full forensics picture may not always have been possible given the evidence my team was working with, the integration of forensics intelligence helped to form scenarios on what may have happened, or was used to identify other opportunities for investigation. Ray was the specialist advisor to the MPS on murder. He was very much a part of my team.

Along with other initiatives, the programme saw Londons murder rate fall from 200 to 125 people per year. That meant seventy-five fewer victims and seventy-five fewer sets of bereaved families and friends. The programme was later extended to the rest of the UK, to Europe and beyond, with Ray a key part of its development.

Another case was the ritual murder of a little boy whose body was found floating in the River Thames in 2001. Rays contribution to the investigation springs to mind because he proved himself to be a true team player perhaps reflecting his days as a keen sportsman. He worked closely with the police in what proved to be a particularly difficult case.

The case affected us all. We had what we thought was an unidentifiable young child, mutilated and thrown into the Thames. No family or community members were asking questions and we had minimal evidence to go on, beyond what could be gleaned from his small torso and a pair of shorts. Within a few months, senior police officers were reporting that this case was not yielding any suspects, that the victim could not be identified and that other cases were coming in that were putting us under pressure and needed to be investigated. One senior officer directed that the case should be closed. I wasnt having that... we had to try our best.

I set Ray and the Senior Investigating Officer (SIO), Will OReilly, the challenge of obtaining as much forensic evidence as possible. To support them in this task, more than sixty forensic experts from the UK and beyond got together at a weekend conference at Bramshill Police Staff College. It was a conference like no other: the gloves were off, brains were engaged and everyone was encouraged to shout out any ideas however far-fetched, different or bizarre they were. Such an unusual murder required an unusual approach.

From the weekend conference and the teams incredible work throughout, ground-breaking developments were made in using the isotopic analysis of bones. This has gone on to be used in many other cases.

Another case that owes a lot to Rays pioneering forensic work is Operation Minstead, the investigation into a predatory gerontophile who burgled and sexually assaulted more than one hundred elderly people in south London, Surrey and Kent over almost two decades. To help solve the case, we used Ray and his forensic teams pioneering and progressive work on familial DNA.

There is no doubt that Ray was considered by the SIOs as a saviour who, quite frankly, helped them to solve some difficult cases that without his input would have not been brought before the courts.

I trust that you enjoy the read, and also recognise Ray for what he deserves. Well done Ray and thank you from the people of London and beyond.

Next page