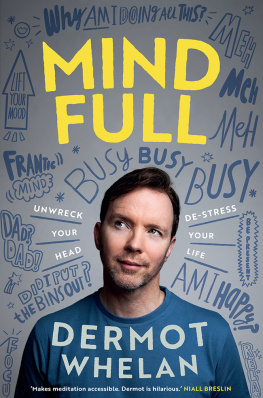

F or the judges and contestants it is time for the final result. The nation has been voting. Im about to reveal who has won X-Factor 2009. Two hundred thousand people have applied and after months of fierce competition this is it. Dermot OLeary stood centre stage once more. Some 400 pumped-up fans were in front of him in the live studio audience. A record 13 million people were watching at home. This was Dermots third year crowning Britains X-Factor champion. It was the biggest moment on TV.

Good luck to everyone. The winner of The X-Factor 2009 is

The clock shows that 23 long and painful seconds passed. On stage Joe McElderry and Ollie Murs closed their eyes and stayed close to their mentors. The X-Factor music pulsed up the tension like a heartbeat. The fans could barely breathe. Then Dermot said it.

Joe!

Confetti fell alongside all the tears. Cheers and applause and even some wails from Ollies fans rang out around the studio. It was the usual moment of pure madness. But Dermot had to regain control. That was his job. It was what he excelled at.

You are absolutely breathless, buddy. Congratulations, mate, he said, his arm around Joes shoulders, his encouragement ringing in the teenagers ears. For as Ollie, Cheryl Cole and Simon Cowell left the stage Dermot had to make sure that Joe was ready to sing that years signature song, The Climb. He had to make sure that a show that had already included performances by Sir Paul McCartney and George Michael ended on even more of a high. And it did.

Controversies would rage in the coming days as an internet campaign was launched to try and stop the X-Factor song from being Christmas Number One as usual. Joes own career might not live up to all the expectations of that extraordinary night in December 2009. But as the credits rolled on the show it was clear that one man was still at the top of his game: Dermot OLeary.

Its easy to argue that the X-Factor job had been something of a gamble for a man like Dermot. Yes, it had given him his biggest, prime time audience and introduced him to a whole new generation of younger fans. But right from the start it had also carried huge risks. If he had messed up then the whole country would have been watching. Perhaps more importantly, if he had done well then the whole world would have wanted a part of him. And for Dermot, surely the most private man in show-business, that would have been the biggest challenge of all.

With three series under his belt and many more to come any fears Dermots fans may have had proved groundless. He had made the show his own. It was live television. It was the biggest show in Britain. It was his.

Y oure eight years old. You hero-worship someone you listen to on the radio and watch on TV. And you finally get the chance to see them in the flesh. Welcome to Dermot OLearys world! Way back in his childhood the man he admired so much was none other than Terry Wogan. And Dermot had the chance to see him at work because back in the early 1980s one of his uncles worked as a security guard at a West London television studio. The studio where Wogan was filmed live, every Tuesday night.

The family connection meant Dermot saw the star-dust of TV long before most of his peers. He would have soaked up the unique atmosphere of a live studio audience. He would have seen all the bright lights hung from the iron girders on the ceilings, the huge cameras in front of the tiny set, the crowds of black-clad workers who darted around talking into what looked like James Bond style walkie talkies. Television would have been a thrilling, secret world full of cool, confident people doing vital, magical jobs. Imagine experiencing all of that at just eight-years-old. No wonder Dermot was hooked. From the first moment I thought, I want to do that, he told Sunday Telegraph reporter Paul Morley years later.

Just how he might achieve his goal was another matter. For the OLeary family, like most of us, had no other connections to the glamorous world of TV. If Dermot was to follow in Terry Wogans footsteps he would do so through his own grit, graft and determination. And he would do so from the very unglamorous starting point of north Essex.

Colchester in Essex is proud to call itself Englands oldest recorded town. Its got deep Roman roots, a castle, a zoo, a university and a military garrison. But what it certainly didnt have in the early 1970s was any form of Irish community. Most of the children born in Colchester hospitals in that decade were given the most popular names of the day. That meant there were an awful lot of very English Claires, Lisas and Julies among the girls, and a lot of boys named Michael, David and James. It also meant that Sean Dermot Finton OLeary Junior, born in Colchester on 24 May 1973, was always going to be something of an outsider.

Dermot himself who was always known by his second name to avoid confusion with his dad, Sean remembers feeling like they were the only Irish Catholic family in the area. True Essex boys of that era headed to the seaside in places like Southend for their summer holidays or went to Spain if they were very lucky and their families had a bit more cash to spend. The only holidays Dermot remembers as a boy were to his parents native County Wexford on the south-east corner of Ireland. Thats where Sean and Maria had lived before leaving for England in the 1960s Sean with just 50 in his pocket and a lot of big dreams in his head.

They hadnt been alone in emigrating. In the 1960s hundreds of thousands of people headed east over the Irish Sea to try and escape the economic gloom in the old country. But while several other members of the OLeary clan had also ended up in England including Dermots uncle at the BBC the majority of them were still in Ireland. So there was always a very big welcome when Dermot, Nicola and their parents headed back for the summer.

The isolation of Essex was forgotten in Ireland. Over there everyone knew everyone else. They walked in and out of each others houses and whole packs of local kids would play together in the fields, woods and streams. It was like the classic, Hollywood image of Ireland, Dermot says. But in his case it was true. Life in County Wexford was as good as his parents had always said it would be. Being Irish seemed the best thing in the whole world.

Even better was the sheer variety of life he found in Ireland far from flat old Essex. As a boy Dermot loved being taken out to the coast for long days by the sea though he admits he was once spooked by a pot of live crabs on Carne Pier, near Rosslare. None of them had been moving when six- year-old Dermot took a close look at them and tapped one with his finger. All were moving and snapping their pincers when he screamed and leapt away in terror. And the story didnt end there. His relatives still joke about how Dermot tried to hide in his uncles VW Beetle and nearly knocked himself out by bashing his head on the door frame on the way in.

The beautiful Curracloe Beach was another favourite place for Dermot. Every spring he would count the days until he could go there again. And when he was on those famous sands he would often close his eyes and try to capture the sound of the waves crashing in the distance. Other kids put sea shells to their ears and tried to hear the sea from them. Dermot tried to hold that sound in his head, so that he could take it back to Colchester at the end of each years holiday.

Staying connected to Ireland mattered a great deal to Dermot, so Irish influences remained just as strong when the family returned home. His dad had been a hurling champion in his youth winning several cups and championships in southern Ireland. Sean was also a keen Gaelic football fan. And he passed that passion on to his son. The two of them would go and see games most Saturdays and bearing in mind that they lived in the Gaelic-free zone of north Essex, this involved a fair bit of travelling. A father and son sitting in a car would naturally bond on long journeys like those. If those trips were all about an Irish sport they would also anchor you even closer to your roots. Might they distance you from the other kids who lived on your street at home? Perhaps. But as long as you had other interests and hobbies you were probably going to be OK. Most Essex boys in the seventies were obsessed by football. So was Dermot. Celtic was his first choice his dad and most of his Irish relatives were fans and to this day Dermot says he gets a thrill when he sees that iconic green and white strip.