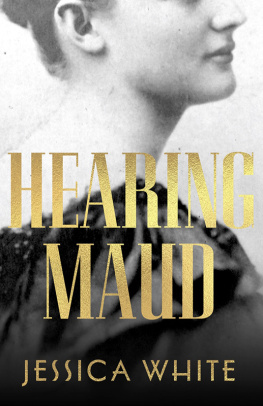

Praise forHearing Maud

This is an extraordinary and poignant memoir written in an embodied and attentive style. White offers us glimpses of global deaf history woven with the tapestry of her own life/story and accentuated with the lives of Rosa and Maud Praed. Hearing Maud is a literary seduction about literary seductions.

Brenda Jo Brueggemann

Lend Me Your EarandDeaf Subjects

In her three-part soliloquy on her search for belonging, understanding and love, Jessica White achieves an extraordinarily accomplished fusion of personal memoir, biography and deaf studies. Whites searching ruminations about the implications of her lifelong deafness together with her scholarly research of Maud Praed the deaf daughter of nineteenth-century Queensland expatriate novelist Rosa Praed and dive into deaf studies resound with tension, drama and insight without yielding to sentiment or polemic. By navigating Mauds heartbreaking story of being deaf in the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries, White locates her own personal Australian experiences of growing up deaf within the panorama of deaf history. In doing so, she not only arrives at an enriched understanding of her deaf self, but also provides a uniquely Australian contribution to the literature of, about and by deaf people.

Donna McDonald

The Art of Being Deaf: A MemoirandJacks Story

In Hearing Maud Jessica White fulfils, with grace, elegance and a fierce regard for truth-telling, writings primary task: to tell it as it is; but as no one has ever told it before. This is a book of wonder. It gives voice to silence.

Martin Edmond

Battarbee and NamatjiraandIsinglass

Jessica White was raised in north-west New South Wales and, at age four, lost most of her hearing from meningitis. An avid reader and writer, she journeyed from her country school of 100 pupils to publishing her first novel at age twenty-nine, before graduating with a PhD from the University of London. Her first novel, A Curious Intimacy, was published in 2007. It won a Sydney Morning Herald Best Young Novelist award, was shortlisted for the Western Australian Premiers award and the Dobbie award for a first book by a woman writer, and longlisted for the international IMPAC award. Her second novel, Entitlement, was published in 2012. Jessica is the recipient of funding from Arts Queensland and the Australia Council for the Arts, and she has been selected for residencies in Tasmania and the Australia Councils BR Whiting Studio in Rome. Her short fiction, poetry and essays have appeared in Australian and international literary journals, including Review of Australian Fiction, Overland, Island, Griffith Review, Westerly and Southerly. Jessica is an academic at The University of Queensland where she is writing an ecobiography of Georgiana Molloy, Western Australias first female scientist. She lives in Brisbane with her partner and a coterie of plants that she tries to keep alive, and she can be found at www.jessicawhite.com.au.

First published in 2019 by

UWA Publishing

Crawley, Western Australia 6009

www.uwap.uwa.edu.au

UWAP is an imprint of UWA Publishing, a division of The University of Western Australia.

This book is copyright. Apart from any fair dealing for the purpose of private study, research, criticism or review, as permitted under the Copyright Act 1968, no part may be reproduced by any process without written permission. Enquiries should be made to the publisher.

Copyright Jessica White 2019

The moral right of the author has been asserted.

ISBN: 978-1-76080-082-6 (epub)

ISBN: 978-1-76080-083-3 (ePDF)

Cover design by Alissa Dinallo

Cover image: Maud Praed, State Library of NSW

Typeset by J&M Typesetting

For my parents, Anne and James

Contents

Prologue

A Poison and a Cure

On a morning in early summer, I lay on a pale-blue trampoline beneath the apricot tree. Its branches, which scraped against my bedroom window in storms, arched over me. The tree was planted by workmen who had lived in our weatherboard cottage before my parents moved in, but it never bore fruit.

My mother appeared at the side of the trampoline.

How are you feeling? she asked.

I shook my head, unable to answer. I was nearly four years old. My head, neck and shoulders were awash with an ache. A light breeze scraped my skin like a blade, while the sunlight, normally soft and dappled, speared through the leaves above.

My mother sensed there was something wrong, she would tell me in later years, something worse than the flu. She thought for a few minutes, then went inside and changed her farm clothes for a skirt and blouse. She collected her handbag, found my shoes and scrawled a note for my father.

Back at the trampoline, she wriggled the shoes onto my feet. Were going to town to see the doctor.

Okay. It was hard to speak.

Mum collected my brother and sister, Oliver and Bella, and dropped them at my grandmothers house a few kilometres away. We then drove over rough gravel roads for forty minutes until we reached Gunnedah. When the local doctor saw me, his movements became quick and urgent: I was to go to Tamworth Base Hospital immediately. Mum drove for another hour. Sweat formed beneath her hands, making the steering wheel sticky.

At the hospital she watched in horror as she held me down while I screamed and the doctor drove a needle into my spine. Results confirmed it was meningitis and I was given a massive dose of antibiotics to kill the infection on the lining of my brain. After that there was nothing to do but wait.

A few hours later my father arrived. My godparents, who lived on a property on the way to Tamworth, rushed in. They sat by the bedside in the darkness while I had a respiratory arrest and stopped breathing. A minister appeared, praying silently with my godparents, who were devout Christians. My atheist parents, having lost a child five years before, held hands against the death of this one.

In the morning, my eyes opened. The adults held their breath. I blinked: ever combative, I had won.

I was in hospital for a month. My bed was adjacent to a sliding glass door that led to a small, fenced courtyard. If kids wet their beds, nurses slung the sheets over the fence to dry. Sometimes those sheets were mine and the nurses chided me for it.

My father often sat beside me, reading from a picture book about Strawberry Shortcake. I twisted the plastic identification bracelet on my wrist, unable to follow what was happening because his voice was a low burble. I liked the pictures, though.

Finally, I was allowed to go home. I tucked my stuffed toys, Mr Tickle and Mr Chatterbox, into the car seat beside me.

Within a few weeks, my parents realised something wasnt right.

She keeps asking me what Im saying, my mother said. This morning I yelled at her down the verandah to clean her teeth and she just looked at me.

Next page