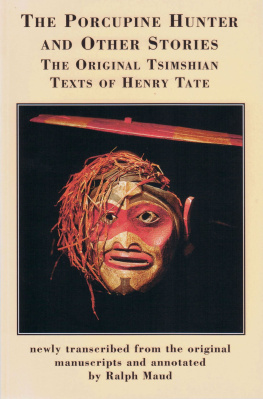

THE PORCUPINE HUNTER

AND OTHER STORIES:

THE ORIGINAL TSIMSHIAN TEXTS

OF HENRY W. TATE

newly transcribed

from the original manuscripts

and annotated

by

Ralph Maud

Talonbooks Vancouver 1993

Other Ethnographic Books by Ralph Maud and Available from Talonbooks

Transmission Difficulties: Franz Boas and Tsimshian Mythologies

A Guide to B.C. Indian Myth and Legend

The Salish People (Vol. I: The Thompson and the Okanagan)

The Salish People (Vol. II: The Squamish and the Lillooet)

The Salish People (Vol. III: The Mainland Halkomelem)

The Salish People (Vol. IV: The Sechelt and the South-Eastern Tribes of Vancouver Island)

About Talonbooks

Thank you for purchasing and reading The Porcupine Hunter and Other Stories.

If you came across this ebook by some other means, feel free to purchase it and support our hard work. It is available through most major online ebook retailers and on our website. The print edition is also available.

Talonbooks is a small, independent, Canadian book publishing company. We have been publishing works of the highest literary merit since the 1960s. With nearly 500 books in print, we offer drama, poetry, fiction, and non-fiction by local playwrights, poets, and authors from the mainstream and margins of Canadas three founding nations, as well as both visible and invisible minorities within Canadas cultural mosaic.

Learn more about us or about the author, Henry Tate, or the editor, Ralph Maud.

Copyright 1993 Ralph Maud

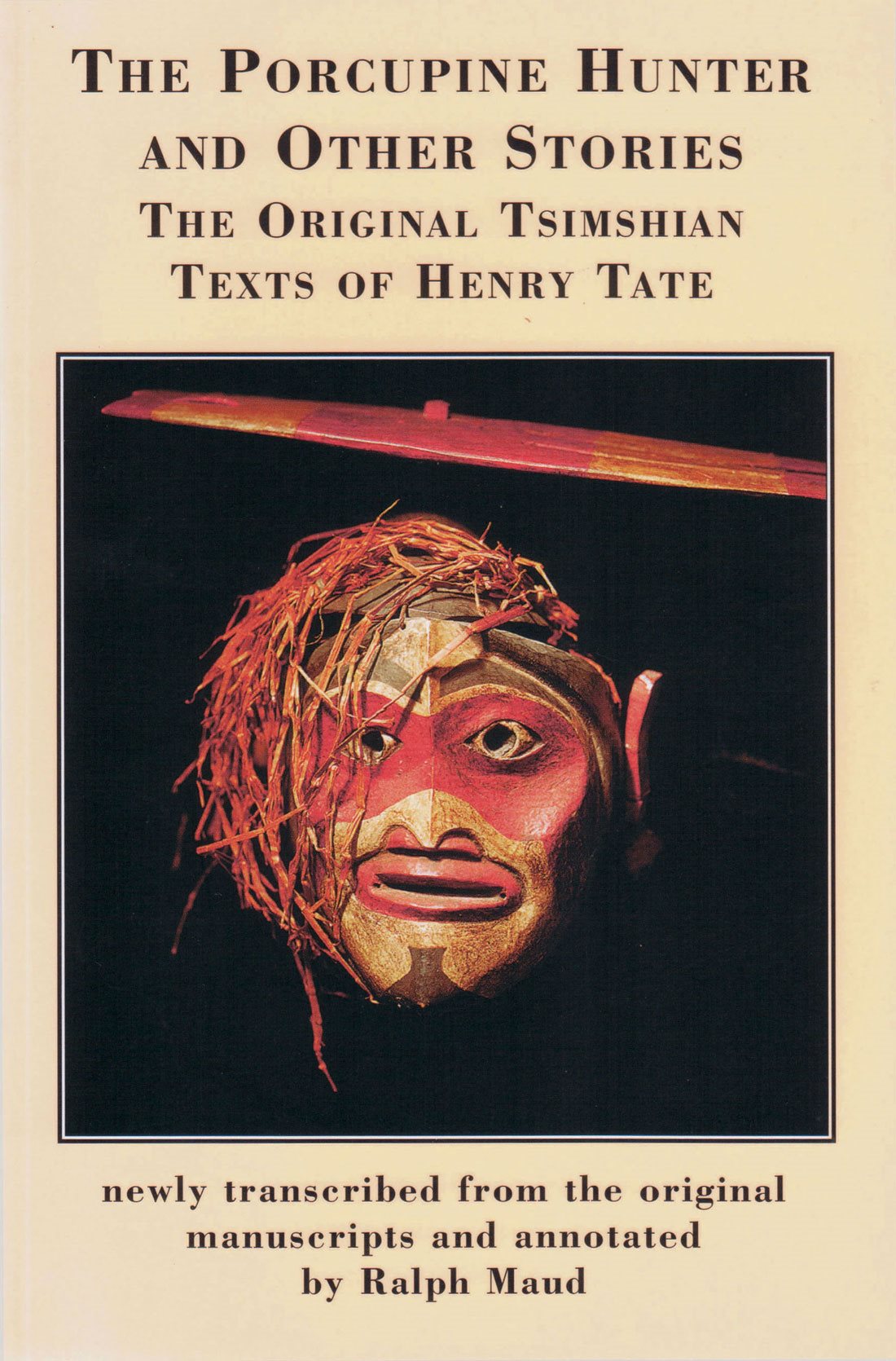

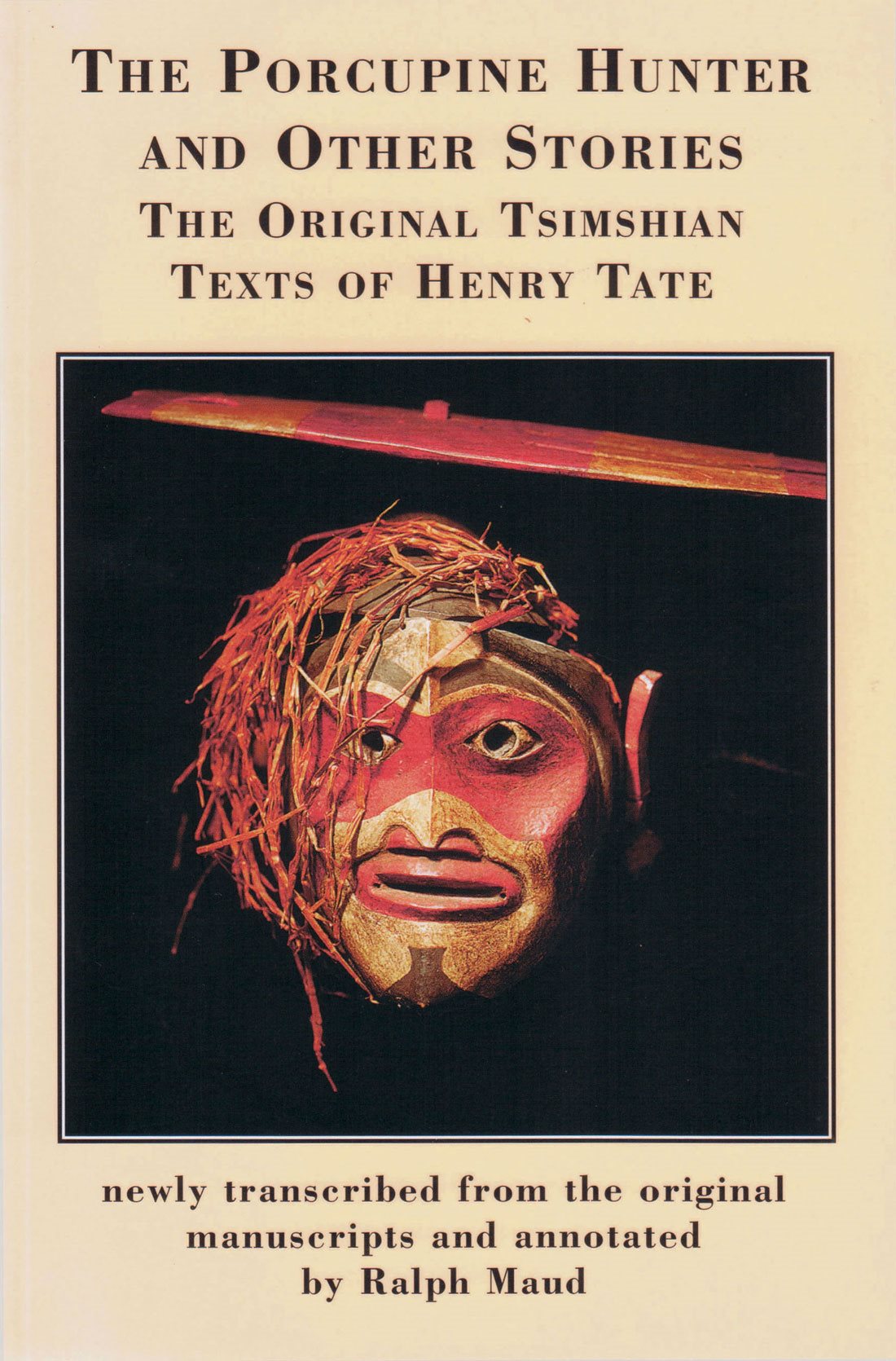

The Cover image is a photo of a Tsimshian mask courtesy of the University of British Columbia, Museum of Anthropology. Photo by Bill McLennan.

Published with assistance from the Canada Council

Talonbooks

278 East 1st Ave.

Vancouver, British Columbia

Canada V5T 1A6

www.talonbooks.com

First Printing: October 1993

Ebook edition: June 2014

Cataloguing data is available from Library and Archives Canada

ISBN 978-0-88922-865-8

CONTENTS

INTRODUCTION

The Girl Who Married the Bear

Grizzly Bear and Beaver

Sun, Moon, and Fog

The Deserted Youth

Eagle Clan Story

Sucking-Intestines

BIBLIOGRAPHY

Introduction

Fort Simpson, later Port Simpson, near the present-day Prince Rupert, B.C., was named after the Hudson Bays chief trader on the Pacific coast, Aemilius Simpson. By the time of Henry Tates birth there, it was an old establishment of a quarter of a centurys trading, and had long been a focus of activity for many of the Tsimshian tribes of the Skeena River, who lived part of the year around the stockade in large rectangular cedar-plank houses.

We can only guess at Tates birth date. He was probably still a teenager at the time of William Ridleys arrival from the Punjab in 1879 to take over the duties of Bishop of Caledonia. Tate must have worked with Ridley for some years on the translation of the Gospels into Tsimshian prior to its publication in 1886, for his subsequent work for Franz Boas shows that he had learnt the Ridley orthography very thoroughly. No missionary can be dull among the Zimshian Indians, wrote the good Bishop in his Snapshots from the North Pacific (London 1903). They have an alertness of mind and purpose which forbids stagnation. He must have had someone in mind when he said this, and it could have been Henry W. Tate.

Tates middle initial stands for Wellingtona name that was possibly acquired at the time of his adoption by Arthur Wellington (Clah), when he was given the status of sisters son within the matrilinear system of the Tsimshians. We know about the adoption because Boas mentions it in the notes to Tsimshian Mythology (1916:500). Its significance lies in the sequence of events which produced from Henry Tates pen the Tsimshian texts of that mas sive volume. George Hunt, Boass trusted Kwakiutl informant, told Boas that if he wanted Tsimshian history and lore he should contact Arthur Wellington (Clah). Hunt was right that Clah was the most notable and verbal of living Tsimshian, but he was quite wrong to think that Clah would or could cooperate in writing down Tsimshian myths on paper. What we have of Clahs manuscripts shows not only a great difficulty with English constructions but also a total commitment to furthering the missionary work of the inspired William Duncan. When Clah received Boass letter of 15 April 1903 he was probably about to go off to do some lay preaching somewhere, to eradicate heathen thoughts from the minds of the populace. Fortunately, he did not tear up Boass letter: he handed it to Henry Tate.

We would know a good deal more about Tate if his first letter, introducing himself to Boas, were extant. As it is, we know hardly anything about him except that, like everybody else, he went up to the Nass every year for the olachen run and did his summer fishing, and that, unlike anybody else, he could write a good clear Tsimshian story in passable English. In the ten years from 1903 until his death in 1913, he mailed to Boas in New York about two thousand pages of interlinear text in English and Tsimshian, a most impressive achievement. Even William Beynon, who does not praise easily, told Marius Barbeau that Tate did not have the full confidence of all his informants...nor money to pay them. In spite of that he seems to have done well (letter of 19 March 1918).

Beynon stresses an important point. Tate was not given money by Boas for informants; he was paid by the page. So he wrote. And who knows how much of what he wrote came out of his own creative talent? Boas does not entertain the possibility that Tate can be anything more than a transmitter of tribal knowledge; and when he publishes the stories, first in Tsimshian Texts (1912) and then in the monumental Tsimshian Mythology (1916) Boas seems only concerned to enter them as raw data for an extensive analysis of myth motifs and culture. A more broadly appreciative view seems called for. Indeed, the reason for the present volume is the acute dissatisfaction one experiences with Boass published texts after one has seen Tates actual manuscript pages. They are much more vivid and engaging than the normalization to standard English in the fare Boas has offered us. Although there are questions of accuracy and distortion that arise in connection with Boass methodology, this edition is not concerned with detailing previous error, but with simply freeing Tate from the previous restraint. The aim is to present the interested reader with the best of Tates texts as found in the original manuscripts, with all their attractive spontaneity, the unpremeditated writing of someone from an oral tradition diving headlong into a new written medium.

The curious thing is that, while Tate obviously spoke and thought in Tsimshian and therefore had these stories in his head in his native language, when he came to write them down for Boas, he wrote them in English first, then supplied the Tsimshian equivalent interlinearly afterwards. This is perfectly clear from a perusal of the documents. Once Boas realized what Tate was doing, he asked him not to (letters of 22 May 1905 and 26 September 1905). Boas wanted the Tsimshian to be the primary text, but Tate, for whatever reason, continued writing the English first as before. So Boas had to make do. Boass loss is our gain, because we have these stories as English compositions, not as translations.

The editor asks the readers trust in the validity of the editorial decisions that produced the final form of the texts on the following pages. There has been a small amount of correction of spelling, punctuation, and grammar. A very small amount. How little has been emended will appear from the myriad non-standard constructions deliberately left in the narratives. If some, why were there not more changes made? It seemed that the quick life of the pieces was contained in the precise actual phrasing, which was not to be disturbed except to avoid something

Next page