This book is number 12 in the African Lives Series, an independent writing and publishing initiative that aims to contribute to a post-colonial intellectual history of South Africa. The series editor is Prof. Andre Odendaal.

First published by Jacana Media (Pty) Ltd in 2018

10 Orange Street

Sunnyside

Auckland Park 2092

South Africa

+2711 628 3200

www.jacana.co.za

Harris Dousemetzis, 2018

All rights reserved.

978-1-4314-2847-2 d-PDF

978-1-4314-2848-9 ePUB

978-1-4314-2849-6 mobi file

Cover design by Maggie Davey and Shawn Paikin

Layout by Shawn Paikin and Alexandra Turner

Editing by Lara Jacob

Proofreading by Megan Mance

Indexing by Harris Dousemetzis

Set in Erhardt MT 9/11pt

Job no. 003387

See a complete list of Jacana titles at www.jacana.co.za

For my Maya-Allende

For Krish Govender, Judge Jody Kollapen and Bishop Ioannis Tsaftaridis; men of courage and principle who took a personal and human interest in Tsafendas when to do so risked establishment contumely and possible professional damage. Their commitment to justice and their principles would not allow them to do otherwise.

For Dimitri Tsafendas

Preface

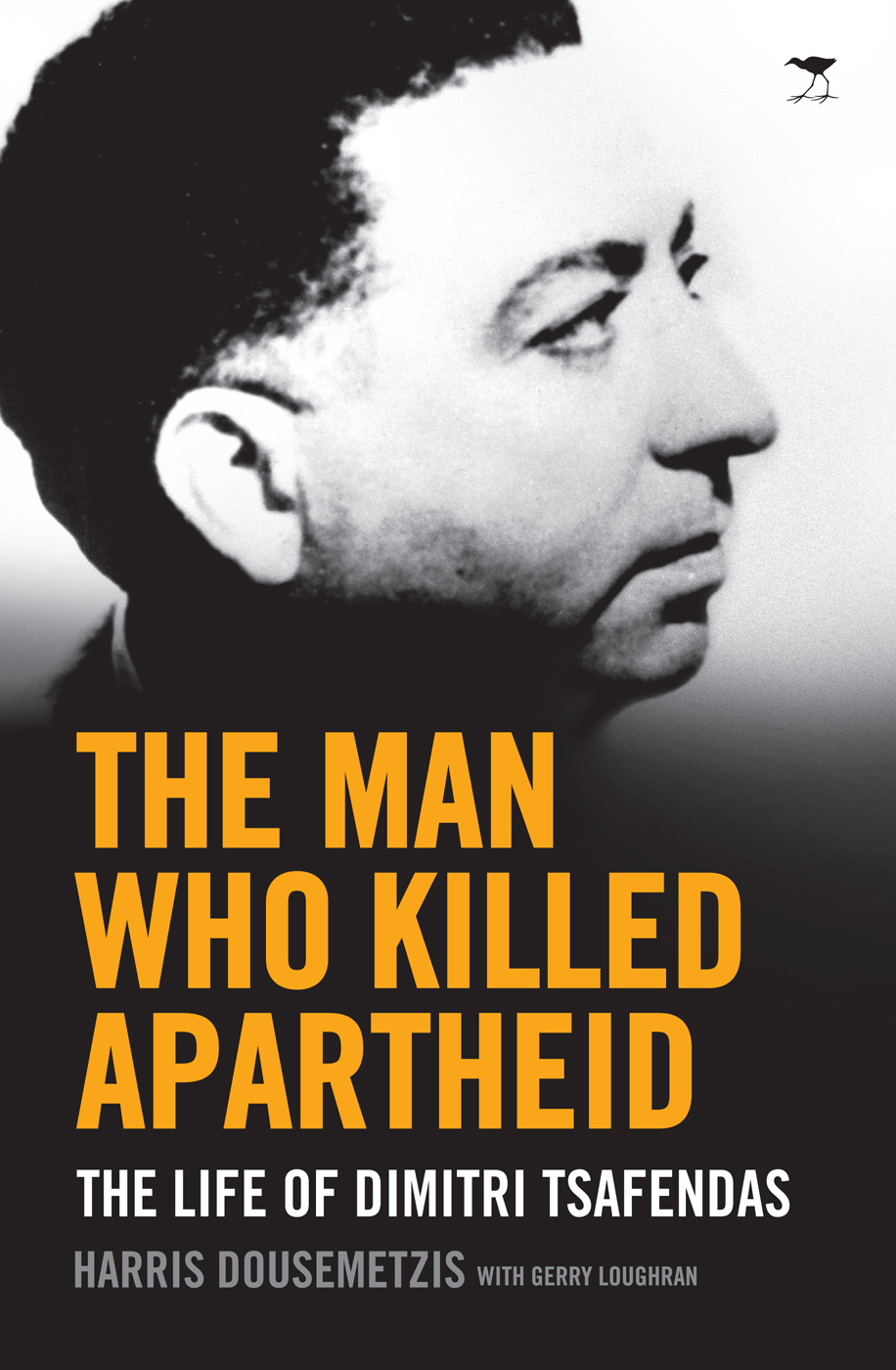

I FIRST LEARNT OF DIMITRI TSAFENDAS when I came across an obituary shortly after his death in 1999. Although familiar with apartheid and a basic history of South Africa, I had never heard of this man. Since the obituary revealed only some basic facts about him, I decided to find out more. Searching further afield, I discovered Henk van Woerdens A Mouthful of Glass, and three other books which mentioned Tsafendas tangentially, Breyten Breytenbachs True Confessions of an Albino Terrorist, Dr Peter Lambleys The Psychology of Apartheid and Gordon Winters Inside BOSS. Reading these volumes prompted me to investigate further since they contained little or no substantive information about Tsafendass trial or the long time he spent in prison and detention. Over the following years, I checked the internet regularly for anything new. A few items here and there, occasional articles in the Greek press and two TV documentaries Manolis Dimelass Live and Let Live and Liza Keys A Question of Madness so intrigued me that I began to think of writing a book about Tsafendas. To do this, I needed to meet people who had known him personally.

In the event, the first five people I contacted turned out to be very important in my work as they had all known Tsafendas well. I spoke to each of them at length and on an ongoing basis, learning facts about Tsafendas, which were not publicly known at the time. The five were Alexander Moumbaris and four Greek Orthodox clerics, Fathers Nikola Banovic, Minas Constandinou, Michalis Visvinis and Bishop Ioannis Tsaftaridis. The three priests had all been close to Tsafendas. Father Minas first met him in Mozambique in 1963 and visited him frequently in prison; Father Nikola shared his home with Tsafendas in Istanbul for more than five months in 1961; Father Michalis called to see him in prison many times over a period of four years. Bishop Ioannis met Tsafendas in prison and although he knew him less well than the other priests, their encounter was a life-changing event for him. As for Moumbaris, he had spent three months in prison alongside Tsafendas in 1973. All of them swore that Tsafendas was perfectly sane and had pretended to be otherwise only to avoid the gallows and that he had killed Verwoerd for purely political reasons. What surprised me was that every one of the five spoke of Tsafendas with unbounded admiration, something I believe would be rare among any random group of five persons commenting on another. Clearly all of these men, four of them ministers of religion, held Verwoerds assassin in the highest esteem and invariably spoke fondly of him not of his deed, but his character. Aware now that Tsafendas was the very opposite of the pathetic figure that had been constructed by South Africas apartheid authorities and sold to the outside world, I decided I would indeed write a book that would seek to correct the record and right a palpable wrong.

Knowing that Tsafendas had befriended the sailors of the Greek tanker, Eleni, shortly before the assassination and aware that these men were central to the police investigation, I procured the crew list from the Greek Ministry of Shipping. I then located and spoke to 16 of the 38 seamen, who all gave me invaluable information about their time with Tsafendas, further confirming the picture of a man who was perfectly sane and deeply political. Over the next few years, I travelled to France, Greece, Mozambique, South Africa and Turkey to speak to more people who had met Tsafendas. I hired private investigators to locate two witnesses I had failed to find, namely Brian Price and Gordon Winter. Their efforts did not bear fruit, but with the help of Dr James Sanders, I was able to interview Winter. Price was the only man I failed to reach. In total, I spoke to 137 people, 69 of whom knew Tsafendas personally, including members of his own family. Some knew Tsafendas exceptionally well and spoke to me formally about him for the first time; five of them had known him since he was a small child. Others included workmates, fellow lodgers, co-prisoners, visitors who talked to him in hospital and prison, clinicians who examined him before his trial, and two of his defence lawyers. Every witness, except for the three members of his defence team, Willie Burger, David Bloomberg and Dr Isaak Sakinofsky, told me exactly the same thing Tsafendas was a normal, sane person with deep political ideas. My interviewees also included persons related to the judicial proceedings such as witnesses, lawyers, judges, psychologists, psychiatrists, academics, high-ranking police officers and former secret agents.

Aware that Tsafendas had been politically active in Mozambique, I searched the Portuguese National Archives and discovered that PIDE, the Portuguese secret security police, held a massive file on him (Secret Criminal Record No 10.415 of Demitrios Tsafantakis). Whats more, I learnt to my astonishment that on the day following Verwoerds assassination, the PIDE in Portugal had instructed their counterparts in Mozambique to conceal from the South African authorities any information indicating Tsafendas as a partisan for the independence of Mozambique and that their colleagues in Loureno Marques had subsequently done exactly that. These were monumental discoveries: I now had in my possession indisputable evidence supporting the testimonies of the witnesses I had interviewed that Tsafendas was a political animal.

By now, I was aware that the National Archives of South Africa contained thousands of documents from the South African police investigations and from the commission of enquiry into Verwoerds death. I was not optimistic as to what I would find since I knew from a number of impeccable sources that Tsafendass first statement to General van den Bergh, who led the police investigation, had gone missing. It was not unknown for evidence to disappear in cases that contradicted apartheids official version of various events or was damaging to the regime. I was surprised, therefore, to discover that the archives held more than a hundred statements taken by the police and the commission of enquiry, along with other evidence, which in some way contradicted the official version of the assassination and supported the evidence I had already collected from my interviews. With permission from Tsafendass family, I also obtained his medical records, which included some documents of major importance such as the Grafton State Hospital report, which revealed that Tsafendas had faked mental illness in 1943 and that the South African authorities were aware of it. In total, about 12,000 pages of documents were discovered and examined, including some from the British National Archives and others from different archival collections in South Africa.