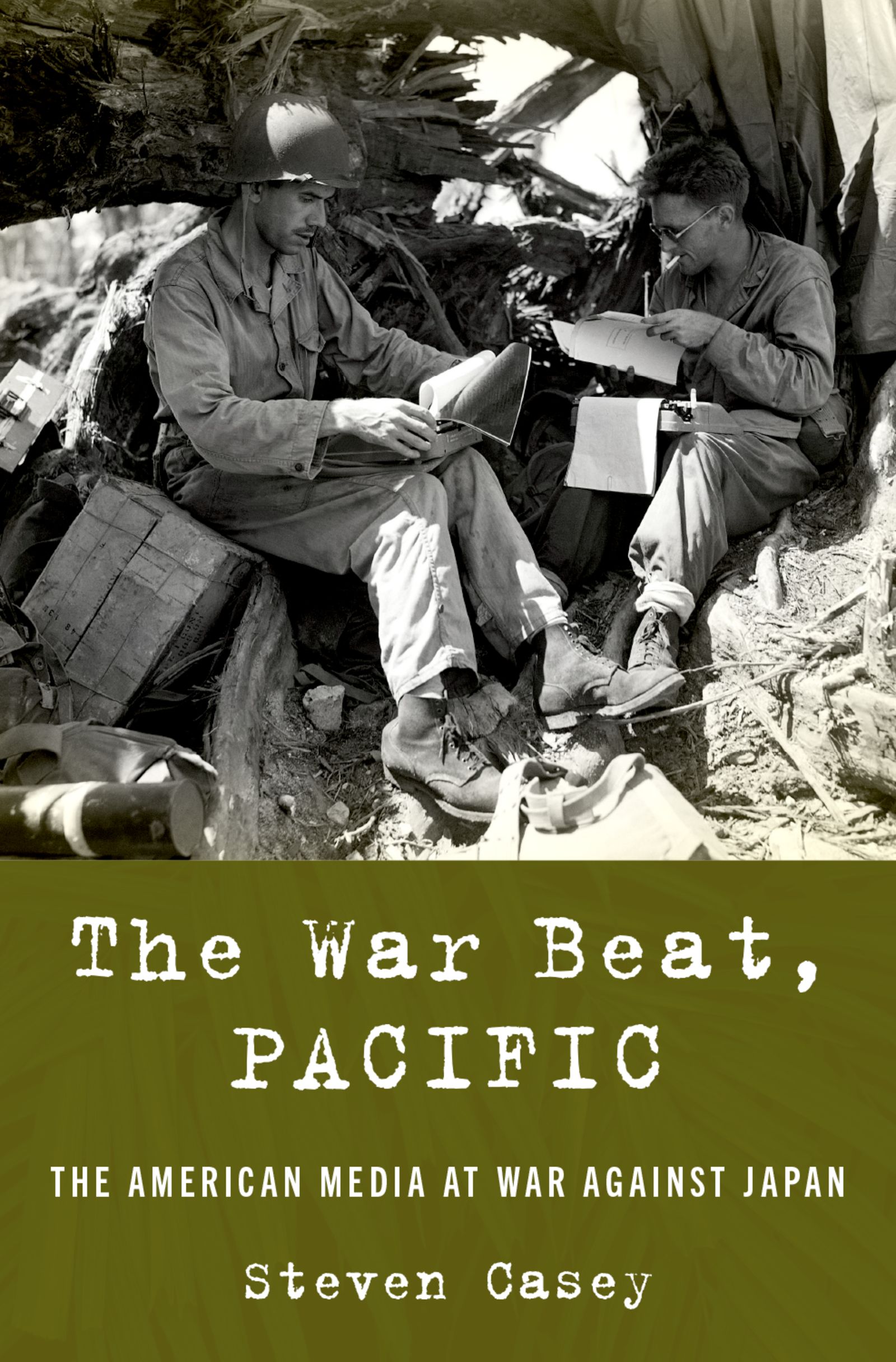

The War Beat, Pacific

Oxford University Press is a department of the University of Oxford. It furthers the Universitys objective of excellence in research, scholarship, and education by publishing worldwide. Oxford is a registered trade mark of Oxford University Press in the UK and certain other countries.

Published in the United States of America by Oxford University Press

198 Madison Avenue, New York, NY 10016, United States of America.

Oxford University Press 2021

All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted, in any form or by any means, without the prior permission in writing of Oxford University Press, or as expressly permitted by law, by license, or under terms agreed with the appropriate reproduction rights organization. Inquiries concerning reproduction outside the scope of the above should be sent to the Rights Department, Oxford University Press, at the address above.

You must not circulate this work in any other form and you must impose this same condition on any acquirer.

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

Names: Casey, Steven, author.

Title: The war beat, Pacific : the American media at war against Japan / Steven Casey.

Other titles: American media at war against Japan

Description: New York, NY : Oxford University Press, [2021] |

Includes bibliographical references and index.

Identifiers: LCCN 2020030386 (print) | LCCN 2020030387 (ebook) |

ISBN 9780190053635 (hardback) | ISBN 9780190053659 (epub) | ISBN 9780190053666

Subjects: LCSH: World War, 19391945Press coverageUnited States. |

World War, 19391945Public opinion. |

Mass mediaPolitical aspectsUnited StatesHistory20th century. |

War correspondentsUnited StatesHistory20th century. |

War correspondentsJapanHistory20th century. |

War correspondentsPacific AreaHistory20th century. |

CensorshipUnited StatesHistory20th century. |

Civil-military relationsUnited StatesHistory20th century. |

World War, 19391945CampaignsPacific Area. |

Public opinionUnited StatesHistory20th century.

Classification: LCC D799.U6 C385 2021 (print) | LCC D799.U6 (ebook) |

DDC 070.4/4999405426dc23

LC record available at https://lccn.loc.gov/2020030386

LC ebook record available at https://lccn.loc.gov/2020030387

DOI: 10.1093/oso/9780190053635.001.0001

For Lauren

Contents

This book is an outgrowth of two earlier projectsone on casualties, the other on war reporting in the European theateron which I have been working since 2008. In that time, I have accumulated numerous debts. I want to begin by thanking the organizations that helped to fund this project, especially the British Academy, which awarded me one of its Small Grants in 2010, and the International History Department at the London School of Economics, which has repeatedly provided me money from its Research Infrastructure and Investment Funds.

I owe a large debt to all the staff members at many archives, especially Valerie Comor and Francesca Pitaro at the AP Archives, James Zobel at the MacArthur Library, Janis Jorgensen at the US Naval Institute, Tal Nadan at the New York Public Library, Hannah Soukup at the University of Montana, Sheridan Bishoff at Syracuse University, Liza Talbot at the Lyndon Johnson Library, Art Miller at Lake Forest College, and Eric Gillespie at the McCormick Archives.

A number of colleagues have read earlier versions of the manuscript. I would particularly like to thank Kevin Bemel, MacGregor Knox, Philip Woods, and the four anonymous peer reviewers. I have been fortunate to work for a fifth time with Susan Ferber at Oxford University Press, and I am extremely grateful for her continued support, advice, and editing expertise. I would also like to thank Mary Becker for her excellent copyediting and Jeremy Toynbee, who skillfully shepherded the book through the various production stages.

My final and most important thanks go to my family: my parents, Terry and Margaret, and above all my daughter, Lauren. This book was completed during the C-19 crisis of 2020, and Lauren, who always lightens up by life, kept me laughing throughout the lockdown. This book is dedicated to her.

The War Beat, Pacific

These differences were manifold. The sheer scope of the Pacific theaterwhich stretched south from China and Burma through the Philippines and New Guinea, and east to the numerous islands dotted across the central Pacifichad no parallel in the war America was fighting in Europe. Simply getting to one of the Allied military headquarters required a much longer journey than a trip across the Atlantic.

As Pyle could testify, wartime London had its obvious disadvantages, from strict rationing to dank winters, but he and most of his colleagues found conditions in the Pacific much more taxing. After reaching one of the Allied headquarters, the correspondents still faced another long journey if they wanted to report directly from the battlefield. A sea voyage entailed long periods of boredom on an alcohol-free ship, punctuated by short bursts of terror whenever someone spotted an enemy plane or submarine. An air trip could be infinitely worse. Some of the planes the military used to transport men back and forth were unreliable. Correspondents who boarded them knew they were taking their lives into their own hands, even if their aircraft managed to avoid the terrible

The hardened reporters who managed to survive all of these travails encountered a military machine that was very different from the one waging war against Nazi Germany. War correspondents in the Pacific found Douglas MacArthur and the US Navy much tougher to deal with than Dwight Eisenhower, who managed to forge a relatively constructive relationship with the press. Thrown on the defensive after Pearl Harbor, MacArthur and Chester W. Nimitz not only needed to manage public expectations about the catastrophic defeats in the Philippines and Hawaii, but also had to deny a rampant enemy valuable strategic and operational information. Both pressures pushed them toward extremely strict censorship. Faced with an Allied strategy that prioritized defeating Germany, MacArthur and the navy had to lobby hard for resources to stem, and hopefully reverse, the Japanese offensiveand here, their media strategies differed. MacArthur, based thousands of miles from Washington, frequently used war correspondents to take his case for reinforcements to the American public. The navy, under the leadership of Ernest J. King, rarely saw any need to ease censorship during the first phase of the war. For one thing, the Washington-based King could use his position on the Joint Chiefs of Staff to push for more resources behind closed doors. For another, Kings navy was fighting on a vast ocean in which American ships rarely saw the Japanese fleet. Since neither side had a clear sense of the damage it was inflicting on the other, King was determined not to volunteer any information that might give the enemy an edge.

For war correspondents, dealing with both organizations posed a major test. MacArthur found ways of rewarding those who toed his line, while punishing anyone who strayed. The navy often seemed to take perverse pleasure in alienating any reporter unfortunate enough to be accredited to it for any length of time. Between this and the dangers of getting to and from the battlefield, many correspondents quickly became disillusioned with covering the Pacific War.