The author and publisher have provided this e-book to you for your personal use only. You may not make this e-book publicly available in any way. Copyright infringement is against the law. If you believe the copy of this e-book you are reading infringes on the authors copyright, please notify the publisher at: us.macmillanusa.com/piracy.

DEDICATED WITH GRATEFUL AFFECTION TO THE LABOR FAMILY AND TO THE MEMORY OF IRVING, MILDRED, AND MILO SHEPARD

The truth about its men of genius is something which the world has a right to and will ultimately get.

UPTON SINCLAIR TO JOAN LONDON

CONTENTS

PREFACE

It is easy to criticize him, of course, because his faults are large and obvious, but it is much more profitable to get on the inside of him and sympathize with his outlook on life.

ANNA STRUNSKY WALLING

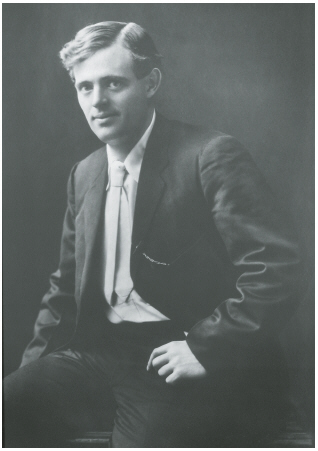

More than a score of books about Jack London have appeared since his death, and while several have been notably insightful, many others have been closer to caricature than reality. No American writer has been subjected to more misleading commentaries. The canards about Londons alleged drug addiction and suicide, to name only two examples, have persisted in the face of clear evidence to the contrary, as have half-truths about his drinking problems and womanizing. At worst, he has been portrayed as a rowdy hack who produced some popular adventure stories for boy-men, a two-fisted he-man who vowed to have one thousand women before he died and who drugged and drank himself into desperate oblivion at the age of forty.

Londons vigorous self-promotion was responsible for many of these distortions, and his sensational exploits made him a magnet for the tabloid newsmongers. Yet even dedicated scholars have been challenged to deal with the complexity of his character. His wife Charmian, who knew him best, may have come closer than any other biographer to explaining this challenge when she said that an attempt to set down his kaleidoscopic personality can result only in seeming paradox. He is so many, infinitely many, things. He is indeed so many things. Most prominent is the popular image of Jack London, Tough Guy. Ask people who know me today, what I am, he wrote to Charmian shortly after their romantic affair had begun in 1903:

A rough, savage fellow, they will say, who likes prizefights and brutalities, who has a clever turn of the pen, a charlatans smattering of art, and the inevitable deficiencies of the untrained, unrefined, self-made man which he strives with a fair measure of success to hide beneath an attitude of roughness and unconventionality. Do I endeavor to unconvince them? Its so much easier to leave their convictions alone.

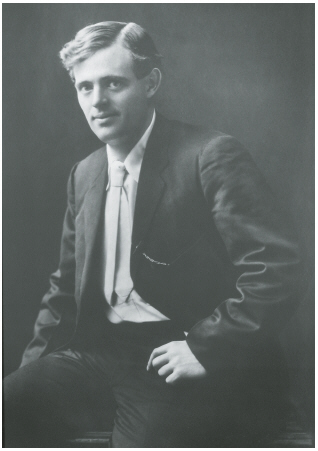

It was also more profitable to leave their convictions alone, and he worked overtime to promote his image as the premier icon of the Strenuous Age. Beneath this persona, however, was a different Jack London: hypersensitive, contentious, moody (possibly bipolar), and medically frail despite his vigorous muscularity. Famous for his ever-ready public smile and generousness of spirit, he was subject to spells of mordant invective and emotional cruelty, especially as his health deteriorated. While he rejected all forms of the supernatural and maintained that he was a thoroughgoing materialist, he regarded Jesus Christ as a great hero and infused his finest work with mythic power. Though devoted to the manly art of boxing and quick with his fists when challenged, he could weep unashamedly over the death of an animal or over a tragic episode in a novel. As he depicted the hero in one of his earliest stories, though the attributes of the lion were there, was there wanting a certain softness, the hint of womanliness, which bespoke the emotional nature. Perhaps the famous portrait artist Arnold Genthe described him most accurately: Jack London had a poignantly sensitive face. His were the eyes of a dreamer, and there was an almost feminine wistfulness about him. And yet at the same time he gave the feeling of a terrible and unconquerable physical force.

Granting the large and obvious personal faults to which Anna Strunsky Walling alluded, the unembellished facts of Londons career are the stuff that dreams and legends are made of, more fabulous than anything Horatio Alger ever imagined. Here was an infant born out of wedlock into near poverty, one whose paternity has never been definitely established. Here was the child who spent his precious boyhood years delivering newspapers, hauling ice, and setting up pins in bowling alleys to augment the familys meager income. Here was the mere youth forced to become a factory work-beast, apparently condemned, like thousands of other poor unfortunates in his social class, either to die an early death from overwork, malnutrition, and disease or, if he deserted his post at the machines, to spend what miserable life that was left in him wandering the underworld among the social degenerates and misfits known as the submerged tenth.

Yet by means of luck, pluck, and sheer determinationundergirded by a rare geniushe succeeded in escaping the pit, transforming himself into Prince of the Oyster Pirates and a man among men at the age of fifteen, able-bodied seaman and prize-winning author at seventeen, recruit in General Kellys Industrial Army (also hobo and convict) at eighteen, notorious Boy Socialist of Oakland at twenty, Klondike argonaut at twenty-one, the American Kipling at twenty-four, internationally acclaimed author of The Call of the Wild at twenty-seven, Hearst war correspondent at twenty-eight, celebrated lecturer and first president of the Intercollegiate Socialist Society at twenty-nine, world traveler on his famous Snark at thirty-one, model farmer at thirty-four, blue-ribbon stock breeder and rancher at thirty-eight, and the producer of more than fifty books (several of which have achieved the status of world classics) before his death at forty. The sum total of these achievements underscores Alfred Kazins comment that the greatest story Jack London ever wrote was the story he lived.

Londons story is quintessentially American. It is difficult to imagine his meteoric rise from rags to riches in a different setting or in a different time in American history. E. L. Doctorow remarks that London leapt on the history of his times like a man on the back of a horse. He rode this horse from his childhood to his death. Even while he was outraged by the inequities and injustices in the American socioeconomic systemand even though his apparent indictment of the myth might seem to be the major theme in his quasi-autobiographical novel Martin Eden as a boy he had already bought wholeheartedly into the Dream of Success. His idiosyncratic political attitude, a peculiar amalgamation of socialism and individualism, was a spin-off of this mythology. The literary historian Kenneth S. Lynn has suggested that Londons conversion to socialism had more to do with rising in the world than with world revolution.

I will elaborate Londons rise in the world in the chapters that follow. Before that, however, Id like to rehearse a few details of my personal connection with Jack London, whose call I first heard more than seventy years ago as a boy in a one-story redbrick schoolhouse nestled amid clean-smelling clusters of pines and oaks in the heart of the Kiamichi Mountains of southeastern Oklahoma. Ours was a consolidated school, meaning that kids, except for the few lucky ones living in the town of Tuskahoma, were bussed in from the surrounding farms on unpaved roads that were dusty in late summer and fall, frost-covered in winter, muddy in spring, and deep-rutted the year around. Six teachers accommodated twelve grades: two grades in each classroom.