CONTENTS

For my parents

PART ONE The City

Going Out

When you met a girl from another factory, you quickly took her measure. What year are you? you asked each other, as if speaking not of human beings but of the makes of cars. How much a month? Including room and board? How much for overtime? Then you might ask what province she was from. You never asked her name.

To have a true friend inside the factory was not easy. Girls slept twelve to a room, and in the tight confines of the dorm it was better to keep your secrets. Some girls joined the factory with borrowed ID cards and never told anyone their real names. Some spoke only to those from their home provinces, but that had risks: Gossip traveled quickly from factory to village, and when you went home every auntie and granny would know how much you made and how much you saved and whether you went out with boys.

When you did make a friend, you did everything for her. If a friend quit her job and had nowhere to stay, you shared your bunk despite the risk of a ten-yuan fine, about $1.25, if you got caught. If she worked far away, you would get up early on a rare day off and ride hours on the bus, and at the other end your friend would take leave from workthis time, the fine one hundred yuanto spend the day with you. You might stay at a factory you didnt like, or quit one you did, because a friend asked you to. Friends wrote letters every week, although the girls who had been out longer considered that childish. They sent messages by mobile phone instead.

Friends fell out often because life was changing so fast. The easiest thing in the world was to lose touch with someone.

The best day of the month was payday. But in a way it was the worst day, too. After you had worked hard for so long, it was infuriating to see how much money had been docked for silly things: being a few minutes late one morning, or taking a half day off for feeling sick, or having to pay extra when the winter uniforms switched to summer ones. On payday, everyone crowded the post office to wire money to their families. Girls who had just come out from home were crazy about sending money back, but the ones who had been out longer laughed at them. Some girls set up savings accounts for themselves, especially if they already had boyfriends. Everyone knew which girls were the best savers and how many thousands they had saved. Everyone knew the worst savers, too, with their lip gloss and silver mobile phones and heart-shaped lockets and their many pairs of high-heeled shoes.

The girls talked constantly of leaving. Workers were required to stay six months, and even then permission to quit was not always granted. The factory held the first two months of every workers pay; leaving without approval meant losing that money and starting all over somewhere else. That was a fact of factory life you couldnt know from the outside: Getting into a factory was easy. The hard part was getting out.

The only way to find a better job was to quit the one you had. Interviews took time away from work, and a new hire was expected to start right away. Leaving a job was also the best guarantee of getting a new one: The pressing need for a place to eat and sleep was incentive to find work fast. Girls often quit a factory in groups, finding courage in numbers and pledging to join a new factory together, although that usually turned out to be impossible. The easiest thing in the world was to lose touch with someone.

* * *

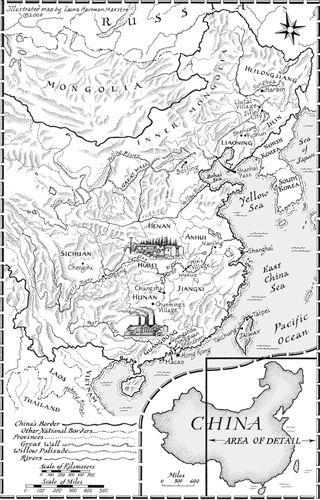

For a long time Lu Qingmin was alone. Her older sister worked at a factory in Shenzhen, a booming industrial city an hour away by bus. Her friends from home were scattered at factories up and down Chinas coast, but Min, as her friends called her, was not in touch with them. It was a matter of pride: Because she didnt like the place she was working, she didnt tell anyone where she was. She simply dropped out of sight.

Her factorys name was Carrin Electronics. The Hong Kongowned company made alarm clocks, calculators, and electronic calendars that displayed the time of day in cities around the world. The factory had looked respectable when Min came for an interview in March 2003: tile buildings, a cement yard, a metal accordion gate that folded shut. It wasnt until she was hired that she was allowed inside. Workers slept twelve to a room in bunks crowded near the toilets; the rooms were dirty and they smelled bad. The food in the canteen was bad, too: A meal consisted of rice, one meat or vegetable dish, and soup, and the soup was watery.

A day on the assembly line stretched from eight in the morning until midnightthirteen hours on the job plus two breaks for mealsand workers labored every day for weeks on end. Sometimes on a Saturday afternoon they had no overtime, which was their only break. The workers made four hundred yuan a monththe equivalent of fifty dollarsand close to double that with overtime, but the pay was often late. The factory employed a thousand people, mostly women, either teenagers just out from home or married women already past thirty. You could judge the quality of the workplace by who was missing: young women in their twenties, the elite of the factory world. When Min imagined sitting on the assembly line every day for the next ten years, she was filled with dread. She was sixteen years old.

From the moment she entered the factory she wanted to leave, but she pledged to stick it out six months. It would be good to toughen herself up, and her options were limited for now. The legal working age was eighteen, though sixteen- and seventeen-year-olds could work certain jobs for shorter hours. Generally only an employer that freely broke the labor lawthe very blackest factories, Min called themwould hire someone as young as she was.

Her first week on the job, Min turned seventeen. She took a half day off and walked the streets alone, buying some sweets and eating them by herself. She had no idea what people did for fun. Before she had come to the city, she had only a vague notion of what a factory was; dimly, she imagined it as a lively social gathering. I thought it would be fun to work on the assembly line, she said later. I thought it would be a lot of people working together, busy, talking, and having fun. I thought it would be very free. But it was not that way at all.

Talking on the job was forbidden and carried a five-yuan fine. Bathroom breaks were limited to ten minutes and required a signup list. Min worked in quality control, checking the electronic gadgets as they moved past on the assembly line to make sure buttons worked and plastic pieces joined and batteries hooked up as they should. She was not a model worker. She chattered constantly and sang with the other women on the line. Sitting still made her feel trapped, like a bird in a cage, so she frequently ran to the bathroom just to look out the window at the green mountains that reminded her of home. Dongguan was a factory city set in the lush subtropics, and sometimes it seemed that Min was the only one who noticed. Because of her, the factory passed a rule that limited workers to one bathroom break every four hours; the penalty for violators was five yuan.

After six months Min went to her boss, a man in his twenties, and said she wanted to leave. He refused.

Your performance on the assembly line is not good, said Mins boss. Are you blind?

Even if I were blind, Min countered, I would not work under such an ungrateful person as you.

Next page