To Maxine

This volume is part of the Smith Institute and BYU Studies series

Studies in Latter-day Saint History.

Also in this series:

Nearly Everything Imaginable: The Everyday Life of Utahs Mormon Pioneers

Voyages of Faith: Explorations in Mormon Pacific History

Copyright 2001 Kathryn H. Shirts and Brigham Young University Press

No part of this book may be reprinted, reproduced, utilized in any form or by any electronic, digital, mechanical or other means, now known or hereafter invented, including photocopying and recording or in an information storage or retrieval system, without permission in writing from the publisher. To contact BYU Studies, write to 1063 JFSB, Provo, Utah 84062 or email .

ISBN 0-8425-2487-8 (hardcover)

ISBN 0-8425-2488-6 (paperback)

LCCN 2001001971

Foreword

T he American West has always been a contested land, a field of battle and conquest. Through most of the twentieth-century, writers and historians have glorified the American triumph in winning the West, portraying its settlers as victors of civilization who subdued and ordered the land and its peoples, wresting abundance and wealth from its hitherto barren mountains and valleys. But in recent years, new western historians, such as Donald Worster, Patricia Limerick and Richard White, have emphasized not the heroic but the rapacious character of western settlers of European descent, seeing them principally as despoilers of the land and its peoples.

Strangely, this discourse has virtually ignored what some have called the hole in the vast donut of the American Westthe Mormon presence. Why would this be? How could astute and sophisticated scholars lavish years of toil examining mining camps, ranching, prostitution, company towns, struggles over water, range wars, women homesteaders, outlaw gangs and corporate greed, and somehow ignore in all this the presence of the Mormons, who, right from the beginning, turn up almost everywhere, interacting with the whole varied procession of other westering folk?

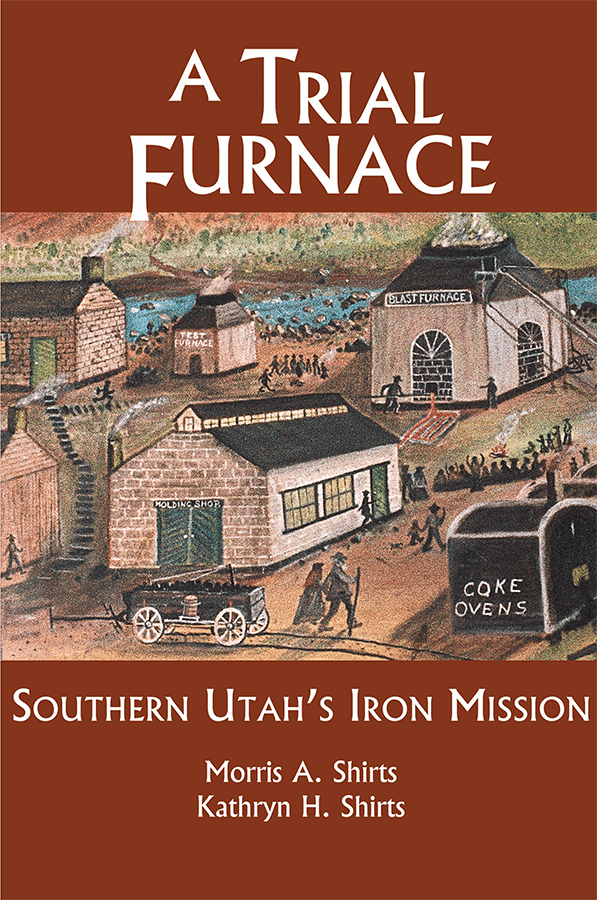

Morris Shirts provides an implicit answer to that puzzle in this long-awaited study of the Iron Mission completed after his death by his daughter-in-law Kathryn. A Trial Furnace is a full and compelling account of the enormous effort Mormons put into developing an iron industry in the Great Basin in the early 1850s. It is a story that chronicles the beginnings of Mormon settlement in the Far West, the development of the called mission concept, and the techniques of its mobilization and application. The effort was headed initially by the much-loved Apostle George A. Smiththe wry, rotund and sometimes irreverent J. Golden Kimball of his time. The mission was the model for subsequent called settlements, the nucleus from which the Mormon domain emerged. It is an epic story that on every page gives the reader fresh insights into how the peopling of the Mormon West was accomplished and how in that process the Mormons were being made saintsundergoing a cultural metamorphosis that began to set them apart from the rest of the West.

Consider, for example, that epic moment when the missionaries fired up their small blast furnace, erected on Coal Creek in present-day Cedar City, after months of bickering, disappointments and backbreaking toil. Rhoda Matheson Wood and Belle Armstrongs colorful account reports that on the eve of the pour, the whole town surrounded the furnace, said prayers invoking Gods blessing, and listened to brief sermons. Then, at dawn, an iron worker took a long rod and knocked out the clay plug, to let a stream of fiery metal pour out.... Shouts of Hosannah! broke from tired, sleepy throats. Henry Lunt wrote more prosaically, Tap[p]ed the furnace about Six oclock a.m. The Metal run out and we all gave three hearty cheers. When the Mettle was cold, on examination it was not found to be so good as might be wished.

It is not the invocation of divine blessing that is unusual in this account. It was common, in fact, for nineteenth-century industrialists to inaugurate their enterprises with such ceremonies. What is unusual is the community gathering, the all-night vigil, the shouting of hosanna when the metal poured forth. The workers were not so much employees of a company as members of a close-knit family and the iron-making effort was pursued not to enrich an Andrew Carnegie but to provide metal vital to the founding of a commonwealth they saw as theirs.

But there was an even more important goal. Lunts concern about the quality of iron reveals but one of a number of thorny problems the iron missionaries had tried to lay down. The enterprise had gone slowly and with much fractiousness. Even as the furnace was being tapped, an apostolic delegation was on its way from Salt Lake City to try to set things aright. When they arrived, as they reported to the Deseret News, we found a Scotch party, a Welch party, an English party, and an American party, and we turned iron masters and undertook to put all these parties through the furnace, and run out a party of Saints for building up the Kingdom of God. The message was clear. As important as the material accomplishment of producing iron might be, it was secondary to the spiritual accomplishment of making saints, of creating a harmonious, cooperative community.

The story of the Iron Mission, as the authors tell it, is poignant. We see pettiness, shortsightedness and backbiting along with stoic, even heroic, dedication. The goal of fostering a successful iron industry eluded these true pioneers, yet theirs is a human story, where real flesh-and-blood people tried to stretch their limited human capacities to span the reach of their lofty vision. And despite hurts, resentments and grumbling, they persisted, their doggedness leading them willy-nilly to accomplish their primary goal, the making not of iron, but of Saints.

It is that communal ethic, the willingness to forego material rewards and individual satisfactions for the community good, that sets these folks apart, making them an anomaly in the West. Like Israelis in the Middle East, the Mormons seem to their neighbors to be cut from a different cloth, a source of bafflement and bewilderment, and hence ignored, shunned or at times even despised. Morris and Kathryn Shirts have brought together their story with a care and richness of detail that gives it life and meaning. Theirs is a solid and enduring accomplishment, an appropriate marker for the 150th anniversary of the commencement of the Iron Mission.

Dean May

University of Utah

Acknowledgments

P ioneer manuscripts are the key to understanding this story. The archives of the LDS Church Historical Department, Utah State Historical Society, Southern Utah University, Brigham Young University and University of Utah have yielded many such documents time after time, thanks to the interest and willing cooperation of their staff members. Individual families in southern Utah have also been generous in sharing family records. Fortunately, Special Collections, Sherratt Library, Southern Utah University, acquired the files of historian William R. Palmer from his family, thus preserving many critical sources on early iron-making operations. Like him, I have shared in the sheer excitement of finding hitherto-unknown journals that shed light on aspects of the Iron Mission.

The search for answers also introduced me to the records of the Deseret Iron Company, to scholarly works dealing with the history and techniques of iron- and steel-making back to the eighteenth century, to LDS Church records, to historical works about Utah and to the deed books of the Iron County Recorders Office. The institutions that have been especially helpful are the Southern Utah University and Brigham Young University libraries, the Utah State Historical Society, St. James Foundation, LDS Church Historical Department, Utah State Archives and Records Service and the Iron Mission State Park.