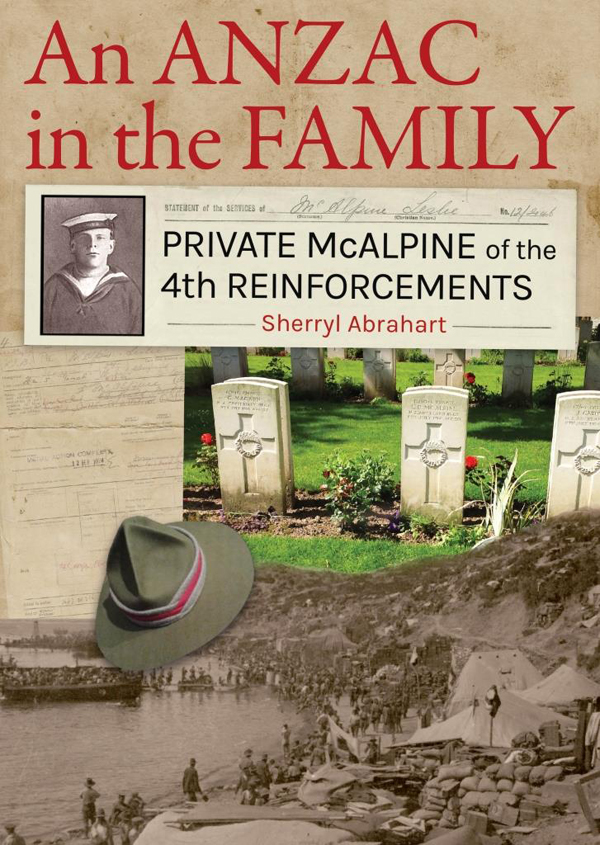

An ANZAC

in the FAMILY

PRIVATE McALPINE of the

4th REINFORCEMENTS

Sherryl Abrahart

Copyright Sherryl Abrahart 2019

First published 2018

All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic, electrostatic, magnetic tape, mechanical, photocopying, recording or otherwise, without the written permission of the copyright holder.

Published under licence by Brown Dog Books and

The Self-Publishing Partnership, 7 Green Park Station, Bath BA1 1JB

www.selfpublishingpartnership.co.uk

ISBN printed book; 978-1-83952-103-4

ISBN e-book; 978-1-83952-104-1

Cover, interior design & maps: Pressgang, NZ

Printed and bound in the UK

This book is printed on FSC certified paper

Contents

I zip up my jacket and slowly linger over the view. The white crosses march out, up and down, neat, tidy, geometrical. The sun dodges in and out of the clouds. The breeze moves the trees on the edges of the cemetery just a little. Its Anzac Day, 25 April. But, here in the northern hemisphere, its not really warm yet.

I walk slowly through the columns and rows of white crosses. Im at the Cit Bonjean Military Cemetery in Armentires, France. Its not my first visit. I come every few years. Its not far from south-east England where I live; its only a few hours off the main road to Paris and its near the friendly city of Lille.

I dont get as emotional as I did on my first visit. First-visit reactions take you by surprise. All the white crosses rows and rows and rows and rows. The search to find your white cross, looking for a reference number. Finding it. Recognising your family name. Imagining the events that left someone from your family in this place.

The grave workers, local French people who have constantly tended all the graves here for almost a century, stop their work and move to the side of the cemetery. They do this to show respect and it makes me feel more emotional. I dont expect such a sensitive level of respect, and their understanding that these fallen men and boys deserve a moment with their descendants is moving and humbling.

My husband wanders off to say hello to the grave workers, hoping they speak English. I find my white cross at II. C. 47. I sit down in front of it and wonder. Uncle Leslie was just 19 when he was killed. What had happened to him? What had the great adventure been like for him?

I become aware of another person moving just behind me. I turn around and smile.

Hi, he says, Im looking for II. D 58. He has an Australian accent.

Think its over there, I say, pointing to my left.

Im Tony, he replies. Were travelling in Europe. Thought Id try to find my great-uncle.

Funny not celebrating Anzac Day properly, as we do back home, he continues.

Yes, but the Menin Gate does a thing, I reply. Worth seeing. Im visiting my uncle hes here, I point.

Strangely, we both feel that we know one another. This young man from Australia and me from New Zealand. We are in a foreign country, halfway round the world. Tied by uncles who fought and died together a long time ago. Its a bond forged immediately momentary but powerful. We have both been raised with the destruction and deaths of the Anzacs.

He moves away and finds his white cross. A young boy, about 10, comes into the cemetery and goes over to him. He puts his arm around the boys shoulders and they kneel together in front of the cross. Its their first visit.

This book is dedicated to all the men and women who served in the First World War. In particular, it is dedicated to the men of the Fourth Reinforcements who sailed away from New Zealand in April 1915. Although they did not take part in the Gallipoli landings on 25 April, many gave their lives on the hills of Gallipoli or on the fields of Western Europe. It is, of course, dedicated to my Uncle Leslie and to his brothers and sisters who missed him and mourned him all their lives.

| Growing up in the early 1900s |

Leslie isnt tall enough to look over the front gate of Grandfather Dandos house. He climbs up on to the first rung of the gate, and squeezes his bare feet between the vertical palings. His knees almost get caught. Hes looking but not quite believing. Wherere all the houses? Wherere all the people? Theres no noise, no trams, no thuds or bangs from the mines. Just trees, hills, bushes and birds, not even a proper road.

He thinks about his home in Waihi, the place they had left a few days previously. Hed lived with his mum and dad (Alice and Fred), his little brother Syd and baby sister Flo, and his dads father, Granddad McAlpine. And he can just about remember Grandma McAlpine too. He had loved being with her. She was always cooking, letting him lick spoons and bowls, with the kitchen full of steam and her apron covered in flour.

Waihi was a sprawling, noisy gold town in the early 1900s. By 1903, when he was six years old, Leslie and the McAlpine family were living in the centre of a town full of people. When he climbed up Granddad McAlpines gate, he could see miners cottages up and down the street, people walking, laughing, arguing, horses and carts. When they drove out in Granddads buggy, towards the end of town, the roads became lanes and the huts became tents. Leslie always wanted to join the children playing around those tents. Envious of their bare feet and wearing what his mum called play clothes, he wondered if they had to clean their teeth, brush their hair and eat everything on their plates like him.

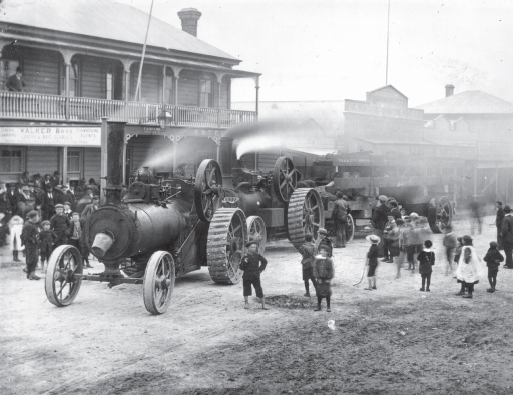

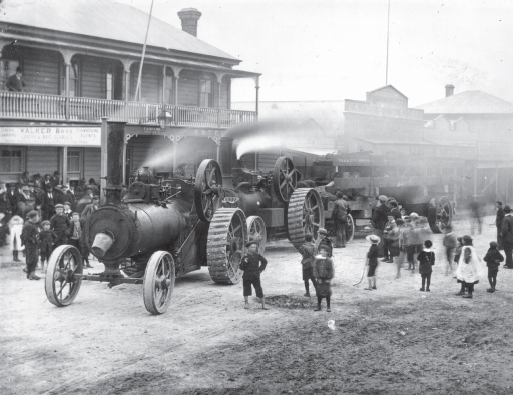

Steam tractors hauling steel beams through Waihi to the Martha Mine around 1900 with lots of excited boys and girls looking on. (Alexander Turnbull Library, 1/2-019316-F)

Leslie didnt really notice the noise, the bustle and the people in Waihi because hed grown up with it. When he went out with his mum or grandma, he could look up the long, straight streets that rose up the hills. He could see mine heads where the goldmines were, where his dad and granddad worked. He and his mum would cross streets carefully and at a bit of a run, because there were tramlines coming down the streets, from the mines to the stamper batteries. His dad had explained how the gold they mined was inside rocks. The trams moved the rocks to batteries where huge stampers crushed them into powder, which was then put in large vats with water and cyanide to extract the gold. Main Street was covered with loose metal, but there were some footpaths, with shops on either side. He would walk down Main Street with his mum on shopping day, usually calling at the general grocery store and the butcher. Sometimes, they would go into Cullen and Co., the drapers, or McLeays, the boot maker. Leslies favourite place was the Ohinemuri Coaching Company, although all hed ever managed was a peek in at the entrance. They had stables with buggies and coaches and lots of horses. Leslie always tried to slow his mum down so he could watch the horses being harnessed. He imagined what itd be like going somewhere in one of those coaches.