Contents

Guide

Contents

Dedicated to Mickey Deane,

shot dead in Cairo, 14 August 2013.

Despite not being fussed about football, he was a great

photojournalist, and a wonderful lion of a man.

Introduction

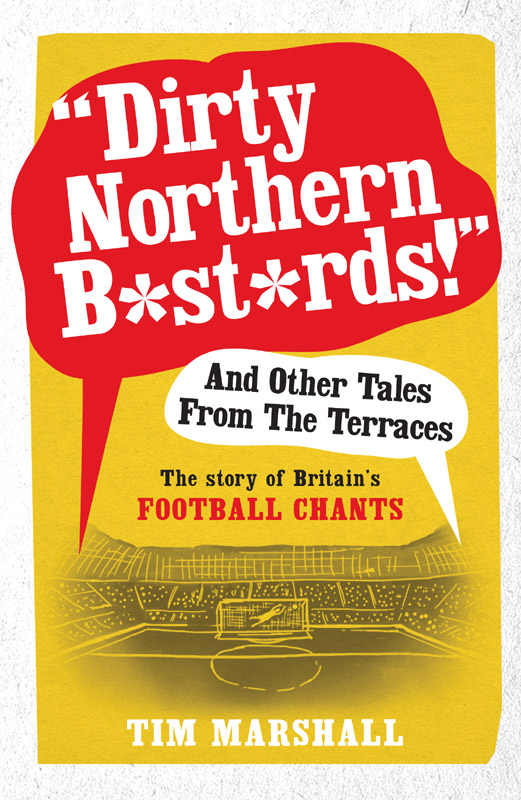

This is a book about the wisdom of the masses, and the madness of the crowd. Its about football and Britain, and Britain and football, because you cannot fully understand one without the other. If you havent got a sense of humour its not worth even trying, as wit runs through both like the Clyde through Glasgow and the writing through a stick of Blackpool rock.

Its about people with a little education and a lot of intelligence, and vice versa. Unfortunately, it also has to be about people with little of either. Crucially, its not supposed to be too serious, but at times you must bear with me the songs and chants will start again. They always do.

My names Tim Marshall and its been a week since my last match. I support a football club. Thats not just five words; its a life sentence.

I came late to the game. You do hear some fans recounting how they first heard the roar of the crowd from within their mothers womb, aged minus four months. More plausibly, others will tell you about being hoisted onto their dads shoulders, aged five, or being passed over the heads of fans to get to the front of the Kop, aged seven. I confess to being a johnny-come-lately ten-year-old when, armed only with a pair of Joe 90 NHS specs and an impressionable mind, I first clicked my way through a turnstile, mounted the concrete steps and emerged into another world.

It was love at first sight, and my first sight was at 2.30 p.m., Saturday, 18 April 1970.

The old adage The past is another country: they do things differently there was only ever partially true and so it is with football.

For the first few years, when I began going, the game was usually on a Saturday afternoon. The crowd was 90 per cent male in the standing areas and the ground would already have been half full an hour before the 3 oclock kick-off. By then the singing would be well under way the PA system didnt bother blasting pop music at us to distortion levels and things would build to a natural crescendo.

By 3 p.m. we were jammed together so tightly that it was difficult to turn around, as your shoulders would be pushing into the people each side of you and there was pressure from front and back. We never thought about these conditions. It was all we knew and, until Hillsborough, all we would know. Behind you there would be a surge of people and you would stagger down three or four steps, struggling to keep your footing, before surging back up the terraces, sometimes having moved across to the left or right by several feet.

The noise was deafening, wave upon wave of songs crashing along the terraces and surging out onto the pitch. The Kop at our ground held 17,000 people, the ground 50,000. Sometimes, in the second half, the PA would announce the attendance. When it came out as being in the 30,000s, and yet we could barely move for the crush, a knowing laugh would go up. It was cash at the gate and we always reckoned that the club, for obvious reasons, might want to knock a few thousand off the attendance figures.

Those were also the days when two of you could push through the turnstile together as long as the guy taking the money got something out of it. Another way of getting in was to slip some money to the man on the sliding gate at the end of the stand. In extremis, you could try to crawl through your friends legs while he fiddled for the right money to give you time to get through the turnstile, but this often ended with a bruised forehead and deep embarrassment when the turnstile man looked down and said, What you doing down there, lad? In that event youd have to go along to the next turnstile and try again.

If the stand behind the goal was sold out, you could try the most difficult trick. Pay the cheaper price for the family section along the side of the pitch, work your way to near the corner flag, then jump over the barrier, sprint across the grass, and dive into the Kop. If you made it, the crowd would part, you would disappear, ducking down as it closed behind you and you worked your way up to where you might, or might not, find your friends. The stewards didnt really care and the police had better things to do than push through hundreds of people in order to catch you.

Try doing that in an all-seater stadium these days. Youd never make it to the stand and youd probably then be arrested and banned for life. Im not defending my various attempts to defraud my club of money, and will be happy to send a cheque for the 5 or so I might have saved over my first few years of attending. But in that culture you didnt think of these practices as wrong, and certainly not as breaking the law. You just chanced it. If you got away with it fine. If you didnt no harm done.

As a young teenager you were stuck more or less in the same spot once the game began. The old stories of the terraces running with urine are true. I never saw anyone piss in your pocket, and think that commonly told tale is a myth, but it wasnt unusual to head across to the nearest pillar holding up the stadium roof and urinate against it. To get from near the back of the Kop to the toilets under the stand was a twenty-minute battle many of us didnt bother fighting. Most of the older, bigger guys would push their way through the crowd to reach the urinals, but people would often refuse to move for a scrawny teenager. When you reached a stanchion, the wall of legs in front of you was impossible to duck under or through.

None of this mattered. It was part of the day and it was about the team. I was lucky supporting one of the biggest clubs in Europe during a successful period. The crowds were huge, the atmosphere febrile. There would be lads standing on the stanchions leading the singing, with just about everyone behind the goal joining in, their 17,000 voices making a wall of noise. Thats when and where I first felt that community spirit, that sense of singleness of purpose, diamond-sharp focus and sheer energy.

All this was replicated on the pitch. The passion for the game was intense, the skills at the highest levels. As young schoolboys, our version of football was to kick the ball, and then run after it. Suddenly I was confronted with passing systems, marking, tactics and creating space. I was dazzled at the patterns being woven across the pitch. It was breathtaking to see one player run five yards with no intention of receiving the ball, but take a defender with him and thus leave a gap for a team mate to run into. This was the beautiful game. When I came across Johan Cruyffs adage that football is a game you play with your brain, the whole thing fell into place. If you doubt the Dutch masters word, then watch a top team, in arrogant cruise control at twonil up, turn into panicked Sunday leaguers if it goes to twoone with fifteen minutes to go. It happens every time.

I came from a family of staunch Methodists, a religion and community I still admire, although as a child I felt stifled by a blanket of non-conformist conformity. Humour and passion are not high on the list of Methodist traits, but now I had found a place where the opposite was true and where revelation was not just a book in the Bible. Soon I was going week in, week out, home and away. I learned more about the geography of Britain from travelling to games than I ever did at the comprehensive school I occasionally frequented. It was the same for all the guys I went with. We all finished our education at sixteen with a thorough grasp of where Coventry is, and where West Ham were in the league table (towards the bottom usually), but little else.