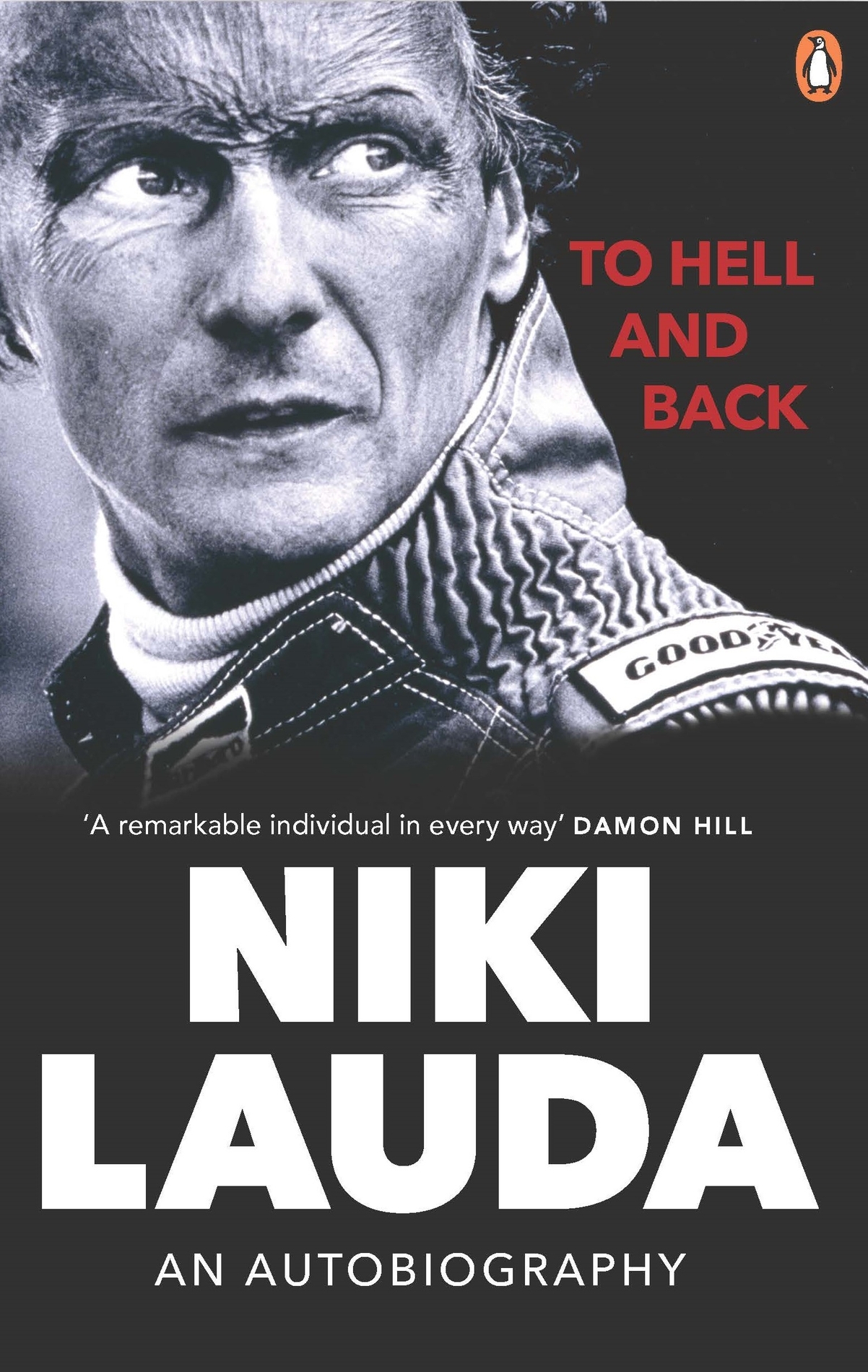

Niki Lauda

TO HELL AND BACK

An Autobiography

Written in collaboration with Herbert Vlker

Translated from the German by E.J. Crockett

Introduction and Postscript by Kevin Eason

CONTENTS

ABOUT THE AUTHOR

Andreas Nikolaus Lauda (22 February 1949 20 May 2019) was an Austrian Formula One driver and three-time F1 World Champion, winning in 1975, 1977 and 1984. A year later, he retired to pursue his love of flying, starting Lauda Air, among a series of aviation ventures, but Formula One always called. He was back in the sport in 1993 as a consultant for Ferrari before moving on to Jaguar and achieveing unparalleled success in the McLaren team with Lewis Hamilton and Nico Rosberg.

INTRODUCTION

THE LEGEND

Kevin Eason

HIGH ABOVE THE phalanx of fans clad in their red caps and shirts was a banner with a haunting picture in stark monochrome of a pair of eyes, scarred by heat and flame, staring down at the bare racetrack below. After the picture was a simple yet heartfelt message: Ciao, Niki.

The occasion was the 2019 Italian Grand Prix, a race steeped in memories and the history of a team that dates back to the very start of the modern era of Formula 1. Ferrari arrived at the fabled Monza circuit celebrating ninety years since Enzo Ferrari founded his eponymous team, the most famous and successful in the world.

This theatre of speed, carved between the trees of the royal park and the sporting home to Ferrari, has provided the stage for some of the teams greatest acts, from Alberto Ascaris first victory at Monza for Ferrari in 1951, the second world championship year, to Michael Schumachers tearful (first) retirement in 2006, just minutes after winning his final race for a Scuderia that he had helped transform into a powerful and dominant force.

This time, victory belonged to the freshest of Ferrari faces, Charles Leclerc, a stripling of just twenty-one years, who provided the champagne toast for the ninetieth birthday celebrations. The man whose eyes adorned that poster and was missing from the Italian Grand Prix for the first time in more than forty years would have grinned and revelled in one of the greatest sights in all of sport as Leclerc clambered onto the elevated podium to see the faithful Ferrari fans, the tifosi, turn the main straight into a river of red with their flags to cheer their new hero.

The memories of many of those teeming fans would have turned to the past, though, and appreciation of the man who looked down on their revelry: Niki Lauda, who died on 20 May 2019, as preparations for the September celebrations reached their climax.

Niki Lauda would have been central to the anniversary party as a key character in the Ferrari story. But he was more than a racing driver, more than a Ferrari driver and more than a man who presided over a team dominating Formula 1 in his final years. He was a symbol of extraordinary courage and determination, whose story was so shocking that even the scions of Hollywood were taken aback when it was committed to celluloid.

The word legend is bandied about too easily in sport: a footballer scores a goal and is instantly crowned a legend, or a boxer knocks out an opponent and becomes a legend because of just one fight. The quote attributed to Ernest Hemingway perhaps comes closest to an explanation of Laudas elevation beyond these lesser legends, beyond even the greatest. There are only three sports bullfighting, mountaineering and motor racing. The rest are merely games, Hemingway said. The intent of his analysis was to show that kicking or hitting a ball or running 100 metres might well be a worthy test of strength or skill, but it is not a contest of mortality.

Niki Lauda drove a car for sport, but crossed the line between life and death and fought back to even greater glory. Lauda really was a legend.

Even people who know nothing of Formula 1 have heard of his crash at the Nrburgring in 1976 when he was dragged from the inferno of his Ferrari so badly injured that he was given the last rites. It was here at Monza before the astonished tifosi that he came back from the dead, racing barely forty-two days after a priest attempted to usher him into the afterlife. His wounds bled, he had no eyelids and couldnt blink, so he could hardly see the track and he was terrified. Enzo Ferrari was horrified by the publicity that surrounded a comeback that seemed beyond human endurance, but the fans descended on Monza in hordes, encouraged by an hysterical Italian press heaping superlatives on this astonishing hero.

There was no heroic return in Laudas mind, though. For him, there was simply no alternative. He disguised his fear behind the fireproof balaclava through which blood seeped, and clamped his red helmet firmly onto his raw skull. Now no one could see the fear, trace the trembling and realise that Lauda was not just pitting his skill against the best, but probing the recesses of his mind where the darkest dread waited. A year later, he reclaimed his world championship for Ferrari.

Laudas first stab at an autobiography came in 1978 with For the Record My Years with Ferrari, translated from the German into English by Diana Mosley, the mother of Max, who provided Laudas first Formula 1 cars from his March factory and later became the controversial president of the Fdration Internationale de lAutomobile (FIA), which governed Formula 1.

His second and last autobiography, To Hell and Back, was published in 1986 after his final retirement, and it was typically Niki to the point with no frills and fancies, no doubt dictated at breakneck speed. It covers the years from his childhood to his accident and the battle for the 1976 title with the charismatic James Hunt, and then his departure from Formula 1 and motor racing as a three-times world champion and one of the most successful drivers in the sport, starting at the bottom with BRM and March, then Ferrari, before moving to the Brabham team run by Bernie Ecclestone, and finally McLaren. But Lauda never updated the book, nor told the story of life after Formula 1 as an airline magnate and then his extraordinary return to the track as chairman of the all-conquering Mercedes team that brought an astonishing five world championships for Lewis Hamilton, plus one more for Nico Rosberg, in successive years.

That was to be my job, and I have attempted to focus on the stories, events and anecdotes that would have been in his mind, which means that this book is part-autobiography, part-portrait of the man behind the mask of scars that became a trademark thanks to the Nrburgring.

I had the privilege as motor-racing correspondent for The Times to meet Lauda on many occasions at racetracks around the world, and there was one thing a journalist could rely on that Niki would have an opinion on almost anything to do with motor racing. His opinions carried unique weight, though, because he had been there, done that and got the scars to prove it. Laudas image was of a bombastic, curt, driven, even impolite man, and he was all and none of those things, but the measure is that he was adored around the world, could charm even the grumpiest of associates and became one of the most revered of countrymen in his homeland of Austria. John Hogan was the mastermind behind the Philip Morris Marlboro sponsorship that invested hundreds of millions of pounds in Formula 1, including backing Lauda. According to him, Lauda was incredibly well-mannered, particularly to women, Hogan said. He was always interested in people and put them at their ease. Women of all ages adored him. I think it was his upbringing because, despite his image, he was always courteous and polite.

Next page