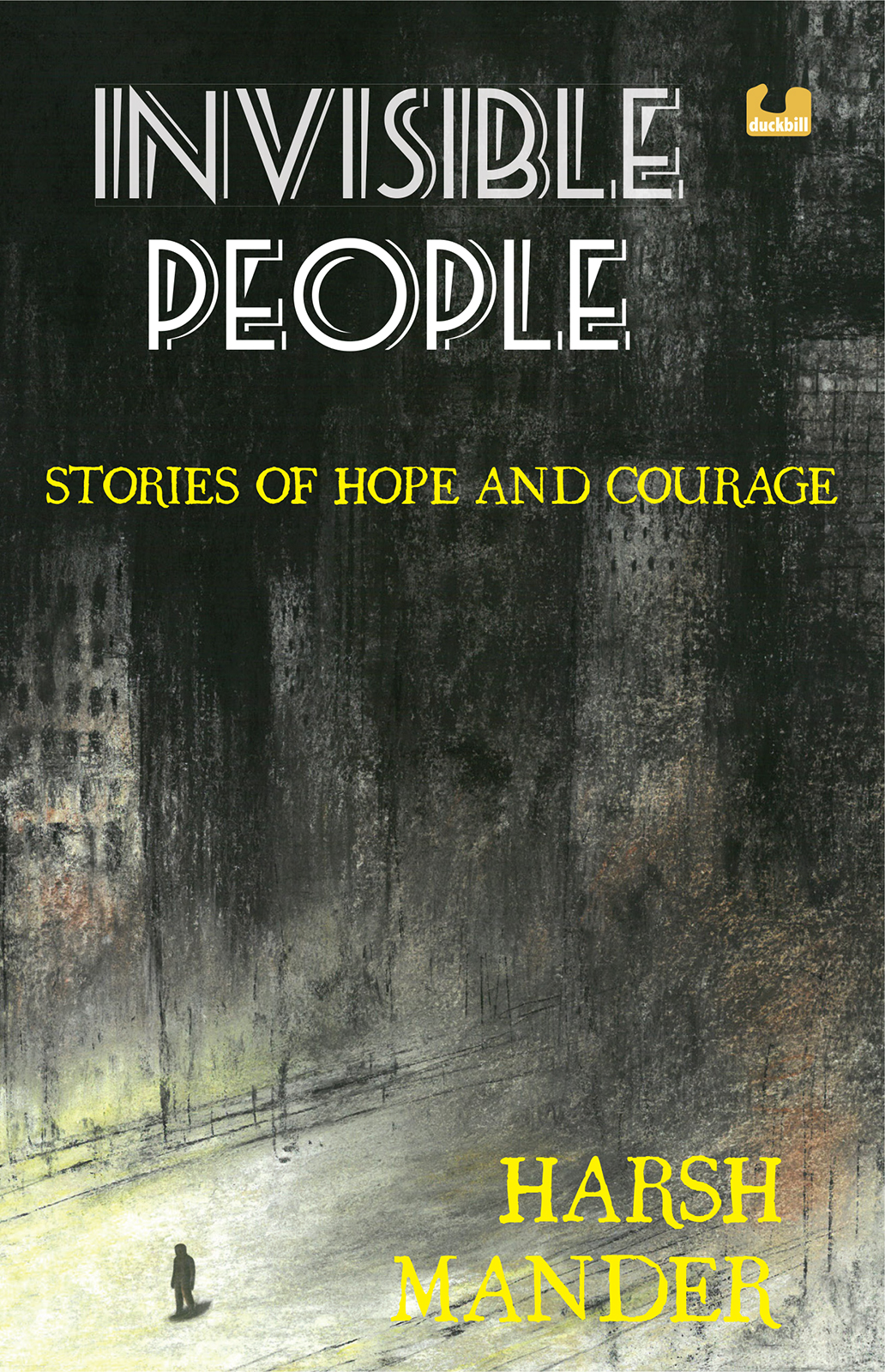

FOREWORD

This book is a chronicle of memories. Memories of begrimed city pavements and demolished slums. Of hunger and stolen childhoods. Of life within and beyond prison walls. Of hate in the air and blood on the streets. Of stigmatised castes. These are narratives from an India which few of us who read this book will ever encounter.

There is nothing in the stories that I have fictionalised. I have tried to recreate faithfully the narratives of the protagonists as recalled by them. I have only changed some names, to preserve confidentiality.

The stories have been written over many years. In the nature of stories, they have a beginning and an end. But the people have, of course, continued to live beyond the ending of the story. I have updated a few of the stories, but many I have chosen to leave in the form they were originally written in.

Many of the young actors in the pages of the book have triumphed, some have been defeated. But every one of them has fought and resisted.

Their stories are not just of epic, sometimes incomprehensible, suffering. They are also stories of the most extraordinary courage and hope under fire, love amidst slaughter, beauty in squalor, generosity in penury and dignity in profound want.

A devastating tornado of fury raged through Rahuls heart. It died down almost as quickly as it rose, but it was too late.

Infuriated by the refusal of his employer to pay him his accumulated wages, the teenaged domestic help had impetuously picked up an iron vessel in the kitchen and smashed it on her head, repeatedly. She screamed, struggled briefly, then collapsed on to the kitchen floor, and lay, motionless, bleeding profusely.

Rahul was more frightened than he had ever been in his life. He ran blindly out of the flat to the nearest bus stop. It was deserted. As he crouched in a corner, weeping inconsolably, the terrifying reality began to slowly seep into his consciousness. He had gravely wounded a sethani, a woman of means. He was not sure that she was dead, but it looked as though she was. He was just fourteen years old, absolutely alone in a strange city, with no relatives or friends to whom he could go for shelter or advice. There was no one to suggest to him a way out of his sudden horrific predicament.

At that moment, he desperately missed his parentstheir humble thatched hut, his remote village in Jharkhand, even the grinding poverty and want. Coming to Mumbai had been a dreadful mistake. He should never have, however hard life had been in his home. His only hope now was to escape and go back forever to his village, before the police discovered his crime.

But Rahul had no money in his pockets, therefore he could not take a bus. Instead, he alternately ran and walked as fast as he could, breathless and panting, to the Chhatrapti Shivaji Railway Station in Mumbai. He asked the porter at the entrance of the station whether there was a train to Kolkota. He was in luck. A train was standing at platform number 8. He ran to it, found the unreserved compartment, and clambered in. He had no money for the train ticket, and hoped he would not be caught without one.

There were barely minutes left for the train to depart, when a police inspector edged his way into the crowded compartment. With him was Rahuls friend who worked in the neighbouring flat. His face was white with fear. When he spotted Rahul, he lowered his eyes in shame at his betrayal.

The two of them, both uprooted from their families, had sat side by side on the terrace of the apartment building on many long nights, sharing memories and dreams, as they fought their loneliness and homesickness. Rahul had often spoken to his friend about his family and his village. No wonder he had guessed that Rahul would rush to the nearest railway station to take the first train in the direction of his village. As his terrified friend identified him, Rahul realised there was to be no escape from this nightmare.

The constables grabbed him by his collar, dragged him to a police jeep, bundled him into the rear, and drove him to the police station. The constables and inspector thrashed him, demanding that he confess his crime. Rahul was too petrified put up any resistance. He immediately told them all that had transpired. The policemen were not too unkind, after that.

The sethani is dead. You will have to go to jail, they told him. If they did not pay you your salary, you should have come to the police, instead of taking the law into your own hands. You have destroyed your life. There is nothing that anyone can do for you.

A constable fed him, after which he sat crouched on his haunches in the police lock-up. Late that night a police team drove him back to the sethanis house. The flat was empty. The police asked Rahul where he slept, where he stored his belongings, and he showed them the scene of the fatal altercation. The sethanis relatives were in the neighbours apartment. When they learnt that Rahul was in the flat, they pushed their way in angrily, shouting, and began to thrash him. But the police restrained them.

That night, Rahul lay on the bare floor of the lock-up, in a restless, fitful, troubled sleep.

The next morning, he was presented before a court. The magistrate grimly heard the charges of murder against him, and ordered a police remand. Rahul returned with his escort to the police station.

The police inspector asked Rahul his age, and he told him that he was fourteen years old. The magistrate had not asked him his age. The inspector took him to a doctor for a medical certificate of his age. In Rahuls presence, the policeman asked the doctor to certify that he was nineteen. The doctor consented without protest.

Rahul got used to the routine in the police lock-up. Since he had confessed to the crime from the start, there was no long interrogation. The police asked him the names of his parents and his village, and photographed him. He was not handcuffed. Foodbasic but adequatecame from a nearby dhaba.