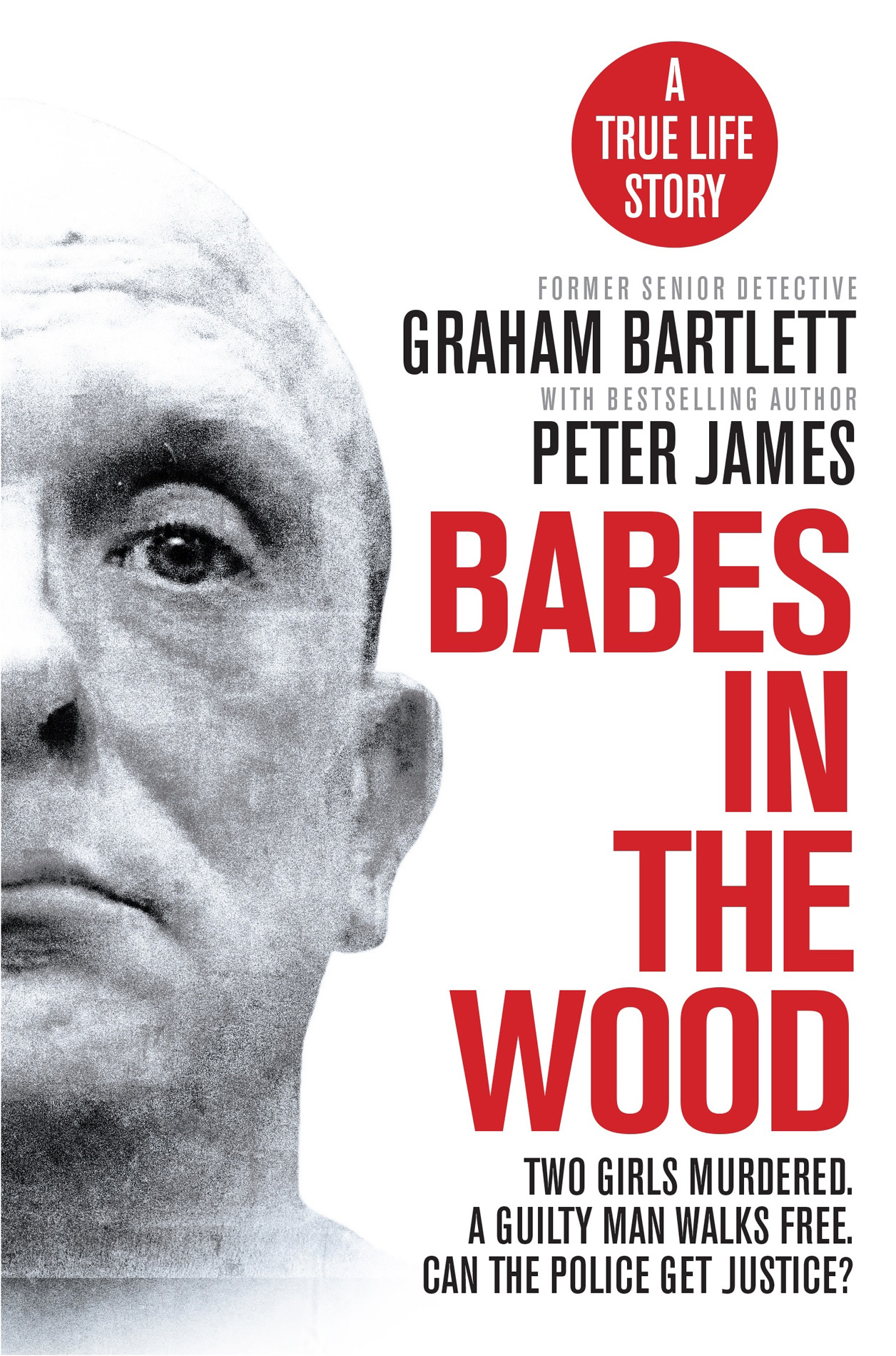

For Nicola and Karen rest in peace

We feel this is an important story to be told, because it shows how one of the nastiest and slipperiest child-killers in UK criminal history so very nearly escaped justice.

CONTENTS

Guide

PROLOGUE

On the evening of 9 October 1986, as the worldwide smash hit musical Phantom of the Opera opened in London, two nine-year-old girls full of excitement, with their lives ahead of them, were about to encounter someone infinitely more terrifying than the blockbusters haunting namesake.

Thousands of children, like them, would have been clutching at the few remaining light evenings of the year, making up for the washout of a summer they had just endured.

It should have been a day that they would never need to remember, melding into similar laughter-filled times that would have defined their carefree childhood. Instead they innocently stumbled upon a real-life monster, someone they knew and should have been able to trust. Someone whose depravity and utter evil could never have been imagined, let alone predicted.

Crossing one road too many trapped them in his clutches and what happened next would shatter two families, a community and a police force forever. It would take a third of a century for the truth of those few heinous minutes to be exposed.

Justice delayed is always justice denied.

PART ONE

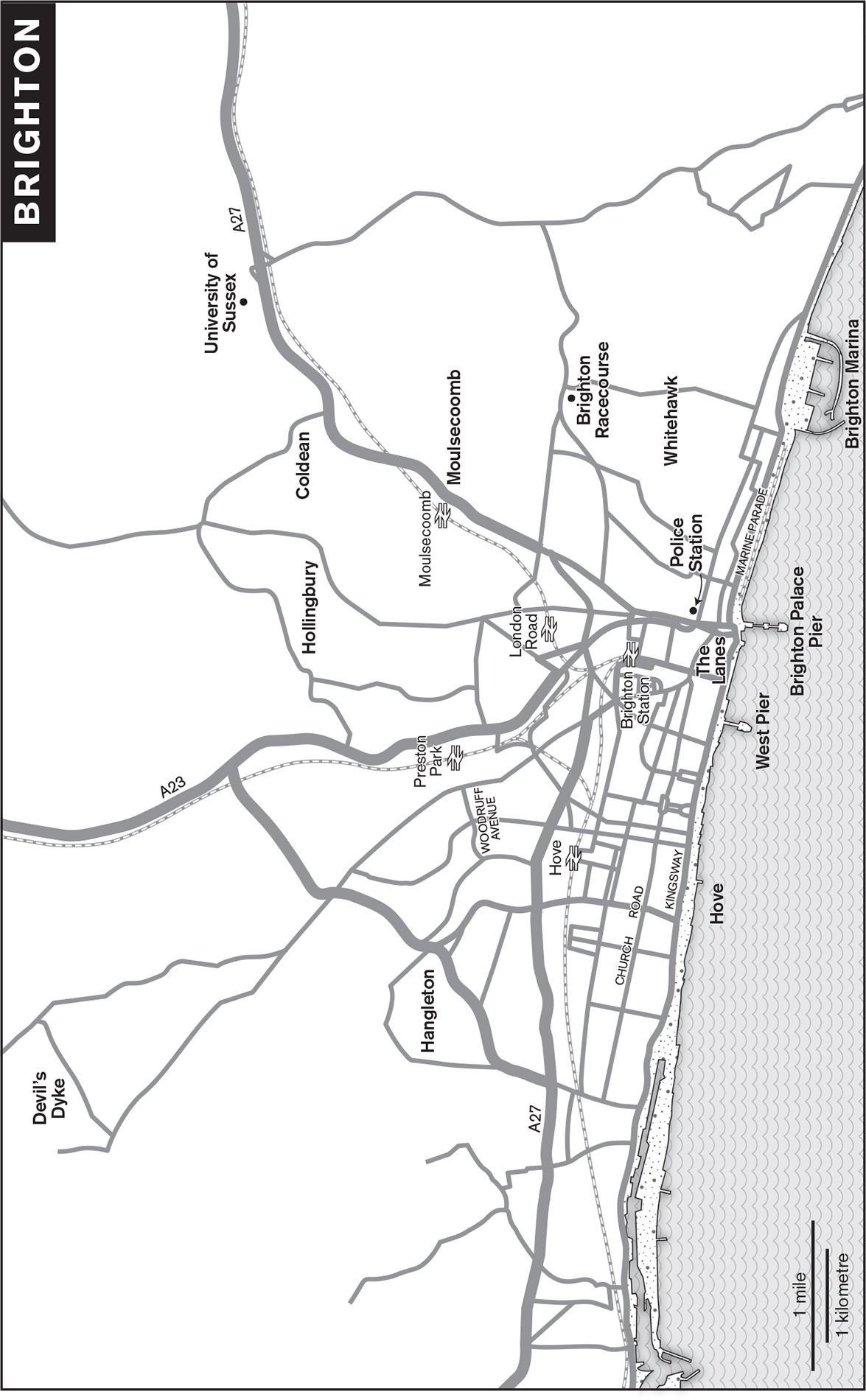

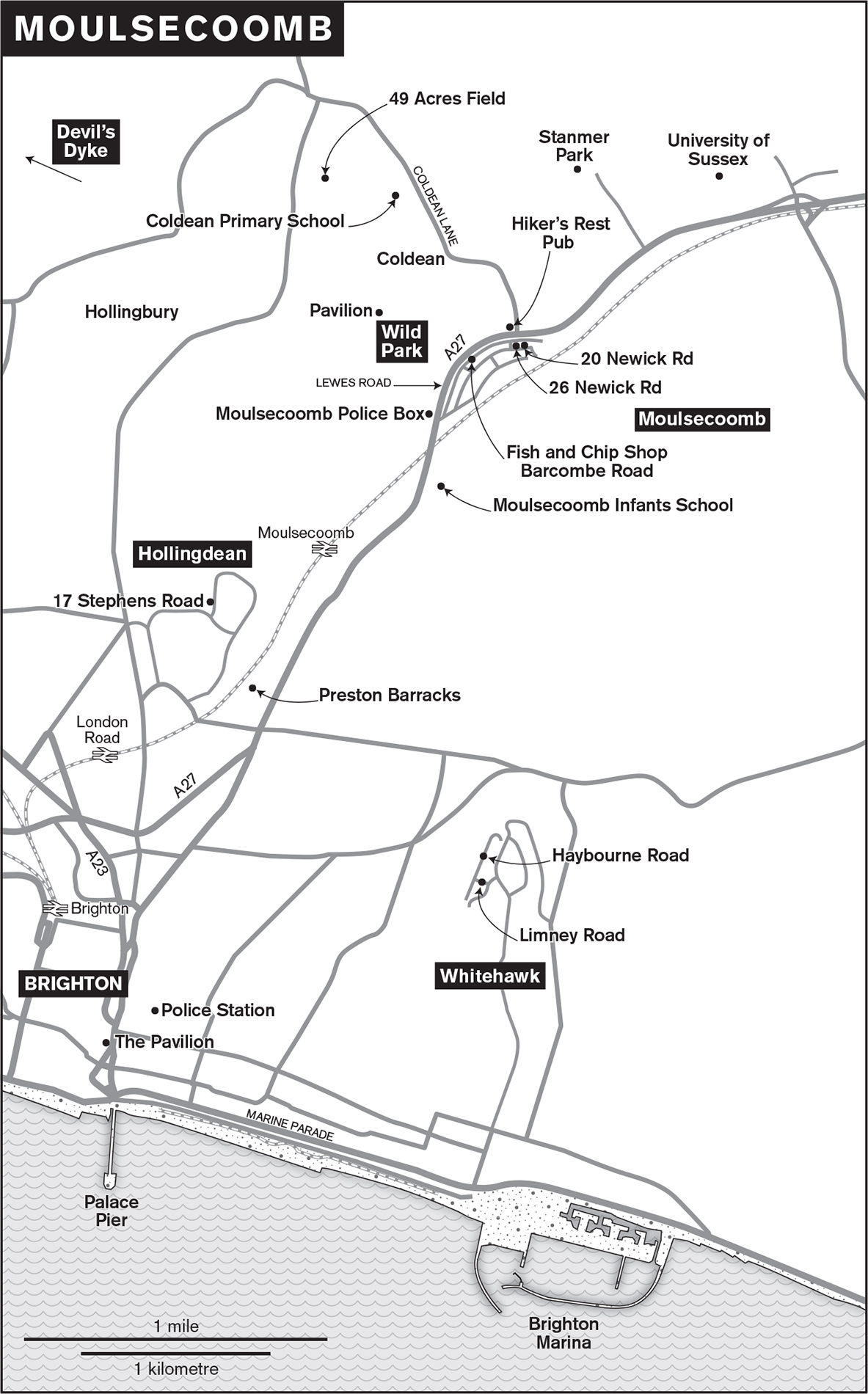

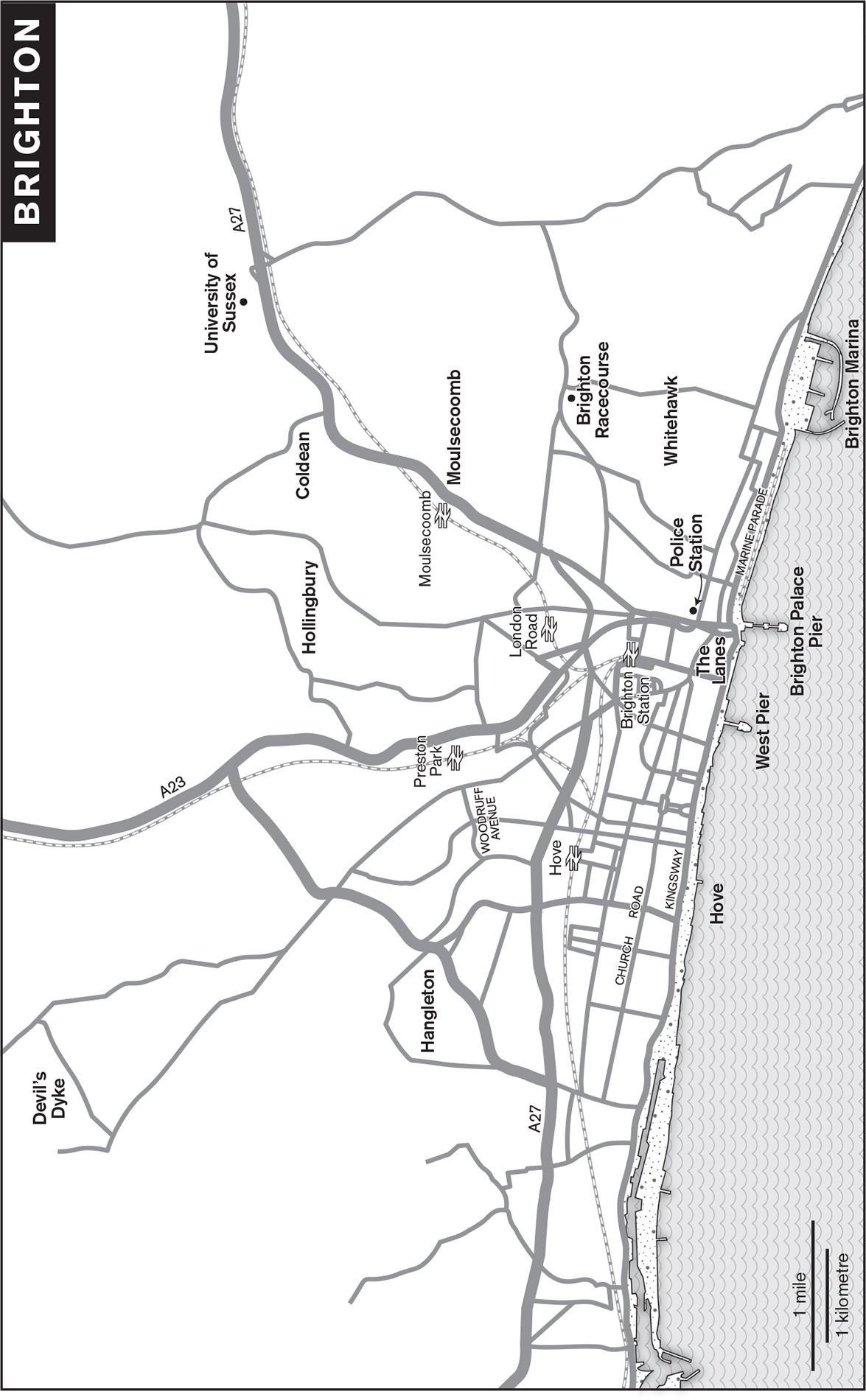

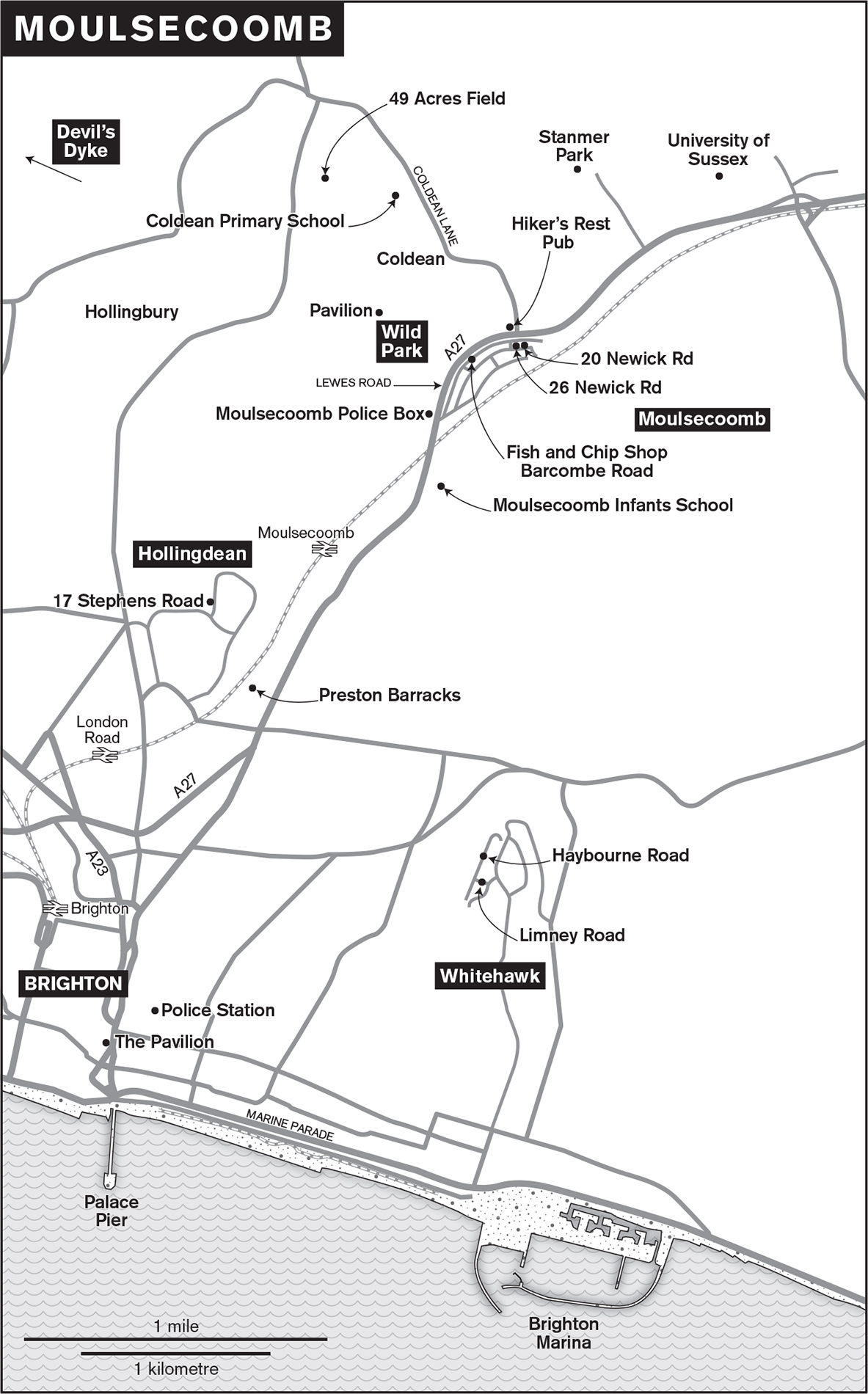

On the northern fringe of Brighton sits a council estate that has lurked under a murderously dark shadow for a generation. The very mention of Moulsecoomb evokes conflicting reactions depending on how you view the world.

If you are sucked in by cheap sound bites and feed off scandal-ridden rumours, you may think of it as a dumping ground for Brighton and Hoves low life; a cauldron of depravation and malevolence into which no outsider dare venture.

If, on the other hand, you can look beyond the provocative headlines and tired brickwork, you will appreciate it as a place that is certainly neglected but is home to a warm and caring community of 9,000, where kids play in the street and everyone looks out for each other.

Its labyrinth of small, tatty semis, crammed higgledy-piggledy along its narrow streets, line one side of the main Brighton to Lewes trunk road. Originally it was built to house returning war heroes in an attractive environment.

Despite the councils lacklustre efforts to spruce up the two and a half square miles of rabbit warren, arguably to fuel the mid-1990s Right to Buy market, the shoddy gardens and perfunctory street lighting gives the estate a dingy feel that its cheek-by-jowl design only accentuates.

Although at the time I was posted to Gatwick Airport, prior to joining the CID in 1990 and the start of my climb to every rank in the city, Moulsecoomb was my patch. In the dedicated response car, my partner PC Dave Leeney and I would constantly be called upon to quell warring families or arrest career criminals. Rarely were we thanked for our efforts and the prospect of returning to find our police car jacked up on bricks, with the wheels missing, was very real.

Like every other officer charged with keeping the estate safe, I saw through this animosity to appreciate a proud and cohesive community where families remained for generations.

The local nature reserve, Wild Park, served Moulsecoomb well. It spills down from the Iron Age site of Hollingbury Hill Fort to the foot of the estate. Its dense woodland and vast grassland provide the perfect relief from the cramped conditions just across the busy road.

Despite its beauty and the affection the locals have for it, nowadays it is synonymous with the horror that unfolded on a single day in October 1986.

I remember it well. My role at the time was to patrol Gatwick Airports sole terminal building, a Smith and Wesson .357 revolver stuffed in my trouser pocket. It was the most tedious detail I endured in all my thirty years service.

I had been posted there in 1985 from Bognor Regis, at the end of my two-year probationary period. Sussex Police had a frustrating policy of waiting until its single officers had been certified as efficient and effective before sending them to Gatwick; a place where millions passed through, but few lingered long enough to commit a crime. Standing watching perfectly ordinary people embark and disembark from certain Irish and Israeli flights and then hot-footing it to security to seize cans of Mace from American tourists who did not know our laws was not why I joined the police. Terrorism, while an underlying threat, had not reached todays levels, so airport policing was more about catching low-level criminals and reassuring the public than being the combat-ready warriors we see today.

The proliferation of single officers made for a great social life though. Most of us lived at the majestic Slaugham Manor, a former country house hotel converted into police accommodation. Its en-suite bedrooms, restaurant (well, canteen), two bars, gym and swimming pool not only made up for the tedious day job but also served as a great party venue, to which we would invite scores of airline and airport staff.

When news broke of the dark events occurring in Moulsecoomb, I was transfixed and desperate to join the hordes of cops drafted in, but I was soon to be disappointed. Apparently my eighteen rounds of ammunition and I were too critical to national security for me to be released. I grumpily resigned myself to watch the events from afar.

At Slaugham Manor, we all held our breath as the details began to emerge.

Best friends Nicola Fellows and Karen Hadaway popped out to play before tea late one early October afternoon.

Nicola, a happy, cheeky and plucky dark-haired cherub of a girl, was the apple of her fathers eye. She made friends easily and was well-liked at school and in her neighbourhood. The precocious exuberance the outside world saw belied the cuddly home-loving girl she really was though. She knew her own mind, and the boundaries. Her mother, Susan, recalled that after rows Nicola would pack her little bag and storm off, saying she was running away. Moments later she would return. When asked what had happened to her plans, she would solemnly remind her parents that she could not go very far, as she was not allowed to cross the road alone.

Barrie Fellows, Nicolas dad, had a tough-guy image which hid the soft-hearted devotion of a family man who lived for his children. An in-your-face Londoner, he moved to Brighton in the 1960s where his brash ways were not everyones cup of tea. His rugged good looks and stocky frame were well known around the estate and he enjoyed his standing as one of the go-to fixers. None of this could prevent his life being ripped apart that day, when he was just thirty-seven.

He and Susan had been married for sixteen years and they lived with Nicola, her brother Jonathan and Susans mother in Newick Road, a run of houses that sits back from the main Lewes Road but just in view of Wild Park. Susan was meeker than Barrie and loved nothing more than being surrounded by her family, of all generations.