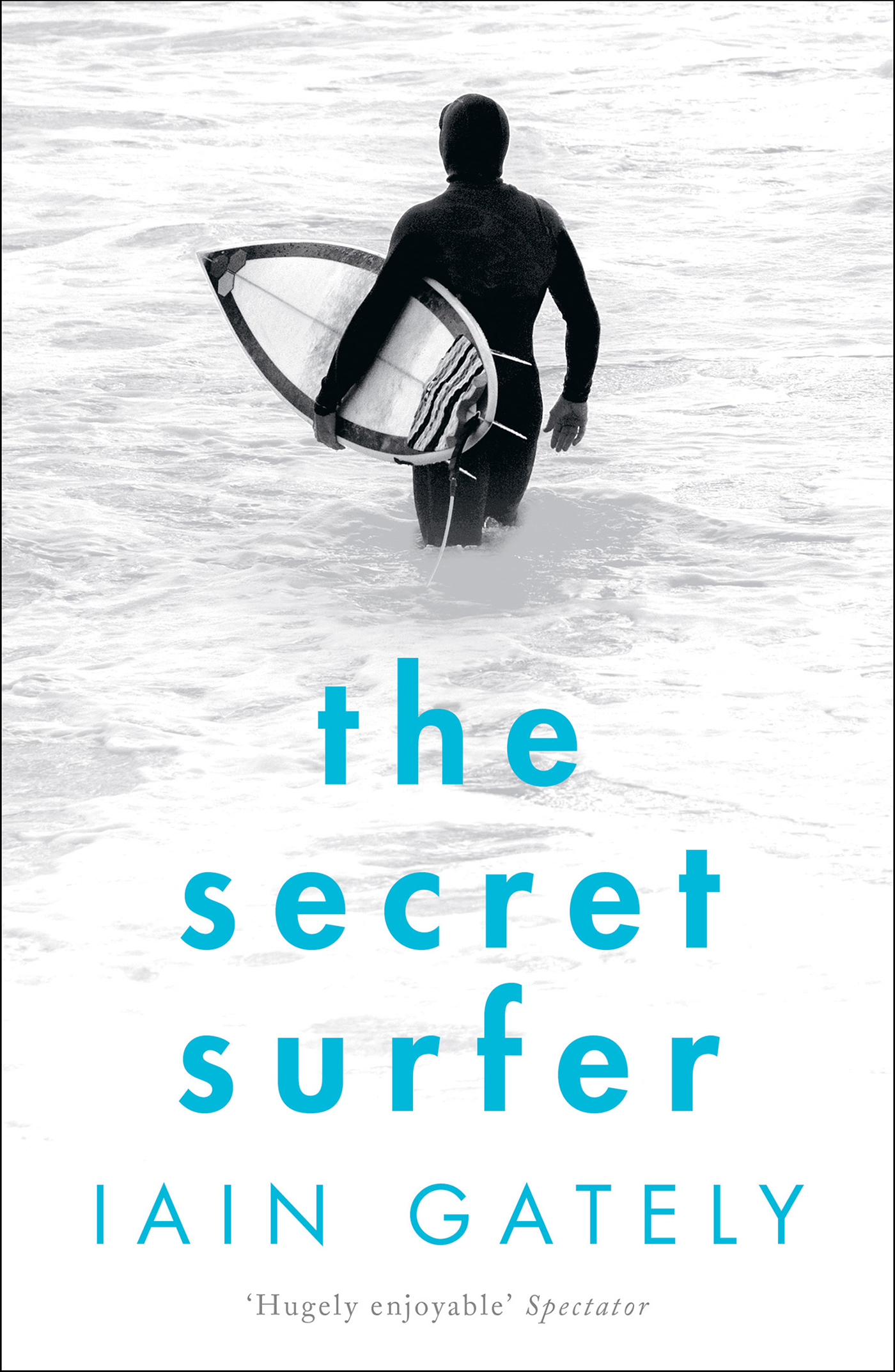

THE SECRET SURFER

Iain Gately

AN APOLLO BOOK

www.headofzeus.com

Recovering from a hip replacement operation, and suffering from a mid-life crisis, Iain Gately sets out to catch a tube. This is no London Underground train, but rather that evanescent space, beneath the lip of a breaking wave, that every surfer yearns to visit. In all his years of surfing, Iain Gately has never caught one. He realises it is now or never.

His quest takes him to the Atlantic beaches of Englands West Country, and to the sandbars and reefs of Galicia and the Canary Islands. By turns funny, energetic and inspiring, The Secret Surfer is a tale of self-knowledge achieved through physical endeavour, a beguiling blend of black humour, adventure and soul-searching. Above all, it is a rousing call to all of us not to give up too soon.

Contents

Staring at the Sea

We moved to Dorset in November 2014. It was stormy all winter and when some friends visited from London in the new year, we walked to the cliffs at Eype to watch waves crashing onto the shingle beach below.

Imagine being out there, at sea, Charles said.

Ive been out there, I told him.

The invitation to imagine sent my memory whirling: Id driven sailing boats through Atlantic storms with giant swells collapsing around me into avalanches of foam; Id paddled out on a surfboard to waves that looked big from the shore and immense when I was among them, lying on my belly and staring at their crests as they turned clear as glass, then shattered and came tumbling down on my head

Yes, said Charles, and frowned. Perhaps he thought I hadnt heard him or that an act of imagination was beyond me. He cupped his hands around his mouth and shouted, Look at the waves, then stabbed a finger at the sea.

I didnt need to look: I could feel them feel the ground tremble underfoot as they detonated against the shore, feel the compression in my ears as each blast passed. And it hurt to be standing on a cliff in Dorset, staring at the medium that in turns had made me brave and scared me witless, fielding inane remarks from an old friend who liked his salt water flat, warm, and clear: St Tropez in summer, the Maldives or Barbados in other seasons; whod dedicated himself to the comforts of life long ago, at the expense of neglecting its challenges.

Like Charles, you can stare at the sea and pretend to be moved, but imagination has its limits. You cant learn much about it from the shore. Even when youre being lashed with spray and horizontal squalls of wind and rain on a cliff top, youre still perched on solid ground, and so insulated from its power and, indeed, vitality . The sea is in constant motion. It flows, rises, spins and judders, and even when its swells are metronomic, as if each were a heartbeat, there are always cross-rhythms that add flickers to its pulse. The glassiest breakers have potholes and bulges on their faces. Tides whirl to and fro beneath flat calms as the oceans follow the pull of the moon. Giant submarine waves, visible only from satellites on clear days, march between the continents in cycles ranging from fourteen days to hundreds of years as the earth spins and bobs around the sun.

Your feelings about the sea change once youve been in it and over it and under it. Its like having a moody and violent lover who teaches you that pain is the price of pleasure, but whos worth the loving nonetheless, and who arouses you in ways that are unimaginable unless youve experienced them.

As we trudged back from Eype towards Sunday lunch, I thought about how I might get back in the sea. Until two years before it had been my playground. Then my left hip started to crumble with osteoarthritis and I lived as a near-cripple for eighteen months. It was bone-on-bone in the socket and when I saw X-rays of the damage, I realized that my body would never heal itself. I had to wait for a hip-resurfacing operation and take the pills in between. That period marked a clear division in my life. I went from being active both in the water and on the land, from surfing, sailing and trekking up mountains, to limping short distances and slumping indoors. I shrank away from physical contact with other people lest they nudged against me accidentally and plunged me into pain.

Defensive behaviour blackened my thoughts: I searched for marks of decay in my friends, to reassure myself that I wasnt leading the pack towards the grave. I delighted when some filled out, slowed down and embraced middle age, as if theyd been seeking it their whole lives. They bought bigger, softer chairs and followed football teams on television with a passion that was disproportionate to either their interest or involvement in the game when young. They also used their children as proxies, deluding themselves that their faculties were still alive, albeit in other bodies, and would tell me with pride how little Simon or India had won the egg-and-spoon race at school, and expect me to congratulate them for the victory as if it had been their own.

My hip was resurfaced in July 2014. Kindly Mr Latham cut through skin and muscle, severed a few tendons, dislocated my joint, whipped the top off my femur, screwed a titanium hemisphere in its place, ground out the socket in my pelvis, cemented a matching metal cup into the bone, reconnected the joint, and stitched up and stapled back together everything hed disturbed, all within ninety minutes. The operation itself is one of those overlooked marvels of medical science like pacemakers that do so much to prolong life or make it pleasant again. A century ago Id have been doomed to spend the rest of my years as an invalid.

Recuperation was mental as much as physical: over the first six weeks, as I passed from crutches to a single stick and then learned to walk again, I enjoyed a rare spell of objectivity. I had to acknowledge that I was middle-aged over the hill and when the ground starts to fall under your feet all is new again. I hadnt felt so uncertain since my teens, when I was on the upward slope, the world was full of a dizzying array of promises and it had seemed that I might ascend forever.

I realized I was faced with two options: the first was to continue the defensive behaviour Id adopted prior to my operation. Since I was falling apart, surely it was best to avoid anything that might hasten the process? Why not give up, grow fat and resort to passive forms of entertainment and vicarious pleasures? I was frightened, however, of the mental damage such a surrender might cause. Would my mind follow my body into decline? Would I in the sense of the I behind my eyes sink into a make-believe world as the grey matter melted? Fantasizing certainly increases as middle age advances: the older you get, the taller your stories. Perhaps this is a rare example of nature being kind, by softening our minds as age withers our flesh. Everybody deserves a splendid past, whether real or imagined. It becomes the substitute for a glorious future when even the most ardent optimist has to acknowledge that their chances of glory have slipped away.

The second option was to behave as if the past two years of pain had been aberrations, and this was more appealing: I wasnt ready to follow the examples of my sedentary friends. I didnt want to put the cork back in the bottle and call it a night. Id rather act as if I was still on the way up the hill and keep alive some of the dreams I had when I was young, of what I might achieve in life, and perhaps even fulfil them. While many have become impossible, or improbable Ive left it too late to open the bowling for England and its unlikely that Ill turn quantum physics on its head, or be called up to fight for my country theres plenty of time yet before senescence and plenty left to achieve, hang onto, or let go of with good grace.