Title Page

WALKING THE HEXAGON

An Escape around France On Foot

by

TERRY CUDBIRD

Dedication

To Peter and Muriel, who first taught me to love the hills, and to Lizzie who accompanied me up many of them.

Publisher Information

First published in 2012 by

Signal Books Limited

36 Minster Road Oxford

OX4 1LY

www.signalbooks.co.uk

Digital edition converted and distributed in 2012 by

Andrews UK Limited 2012

www.andrewsuk.com

Terry Cudbird, 2012

The right of Terry Cudbird to be identified as the author of this work has been asserted by him in accordance with the Copyright, Design and Patents Act, 1988.

All rights reserved. The whole of this work, including all text and illustrations, is protected by copyright. No parts of this work may be loaded, stored, manipulated, reproduced or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic or mechanical, including photocopying and recording, or by any information, storage and retrieval system without prior written permission from the publisher, on behalf of the copyright owner.

Production: Tora Kelly Cover Design: Tora Kelly Cover Illustrations: Elizabeth Manson-Bahr Photographs: Terry Cudbird; pp.9, 63, 69 Wikipedia Commons Maps: www.hello-design.co.uk Printed by Short Run Press Ltd, Exeter, UK

Introduction: Why Walk?

On a cold November day I was walking down a path of slippery cobbles and rain was falling. A grey sky covered me like a shroud. I was crossing the northern plain not far from Valenciennes in the Nord dpartement . Slag heaps dotted the horizon near the large Citron factory at Hordain. It was a scene reminiscent of mile Zolas dark nineteenth-century novel Germinal about the mining communities of this region. And then suddenly I noticed three young men rolling towards me in a four by four. They wore hunting clothes and were obviously on their way back from a days shooting. The driver stopped and lowered his window. What are you doing?

Walking.

Eh! Where have you walked from?

Beaudignies.

An incredulous smile spread across his face. What nationality are you? he asked, as if no Frenchman would be walking in the rain across the bleak plain on a cold afternoon in November.

English.

Do you do things like this in England?

Yes.

His expression suggested that my nationality explained everything. All the English, the French tend to believe, are eccentric.

I received a similar reaction on several occasions during my three hundred-day walk around France. English hikers never look the height of fashion, whereas in France it is important to appear smart even if you are trekking. Well-dressed ladies moved away from me in a tea shop in Brittany, probably because I looked like a bedraggled tramp. In a restaurant near Verdun my down and out appearance provoked pity and a free drink. A caf owner in the north thought I was a poor St. Jacques pilgrim who had come in the wrong season. In the Vende an hotelier politely showed me to the back entrance so as not to shock his diners.

My appearance and my plan to walk around France were not the only factors which struck the French as bizarre. They could not understand why I was walking alone. The French are too sociable to do that, two ladies once said to me. French maps contain red lines for the Grandes Randonnes stretching hundreds of miles, but few people walk a GR for long distances, except in the Pyrenees, the Alps and in Corsica .

Why do third-agers seek adventures like mine? The crazy idea of walking around the circumference of France started with a conversation beside an Alpine lake just before my retirement. I told my wife Lizzie that I wanted to walk a lot of the Grandes Randonnes - the 38,000-mile network of long-distance footpaths that cover the French countryside - and write about my experiences. Why dont you do it now? she said, before you become decrepit.

The best sound in the world for me became the clunk-click of the buckles when I put on my rucksack. It meant the freedom to go where I wanted, to dream my own dreams and escape the complications of everyday life. My project quickly became an obsession. I was never as happy as when I was poring over maps, calculating distances and making timetables. Having spent so much time creating detailed plans I had to carry them out . The timetable then took over. When I first mentioned to friends what I had in mind some thought I was mad. Why wear out your sixty-year-old hips and knees walking around France when you could spend a comfortable retirement doing voluntary work in Oxford and going on cruises? Others were enthusiastic about the idea, looked wistfully at their walking boots and said they would love to join me for a stretch. The itinerary put most of them off when they realised what was involved. How can you keep plodding along day after day? was a common reaction. Why not just do the best bits and leave the rest out? I could not compromise. I had said I was going to walk the circumference of France and round I was going to go.

The idea of such a circular journey is nothing new. The tradition of le compagnonnage , artisans walking round France in search of opportunities to perfect their skills, was strong in the eighteenth and early nineteenth centuries. In 1877 a little book appeared which became a major publishing success, selling seven million copies by 1914. Augustine Fouilles Le Tour de la France par deux enfants described the escape of two imaginary boys from German-occupied Lorraine and their journey around France, rediscovering its towns and villages, its industries, agriculture and historical sites. The famous cycle race, the Tour de France, started in 1903 and ever since has covered large parts of France, sometimes around its periphery. Yet as far as I know I am the only person to have attempted such a long circular tour on foot.

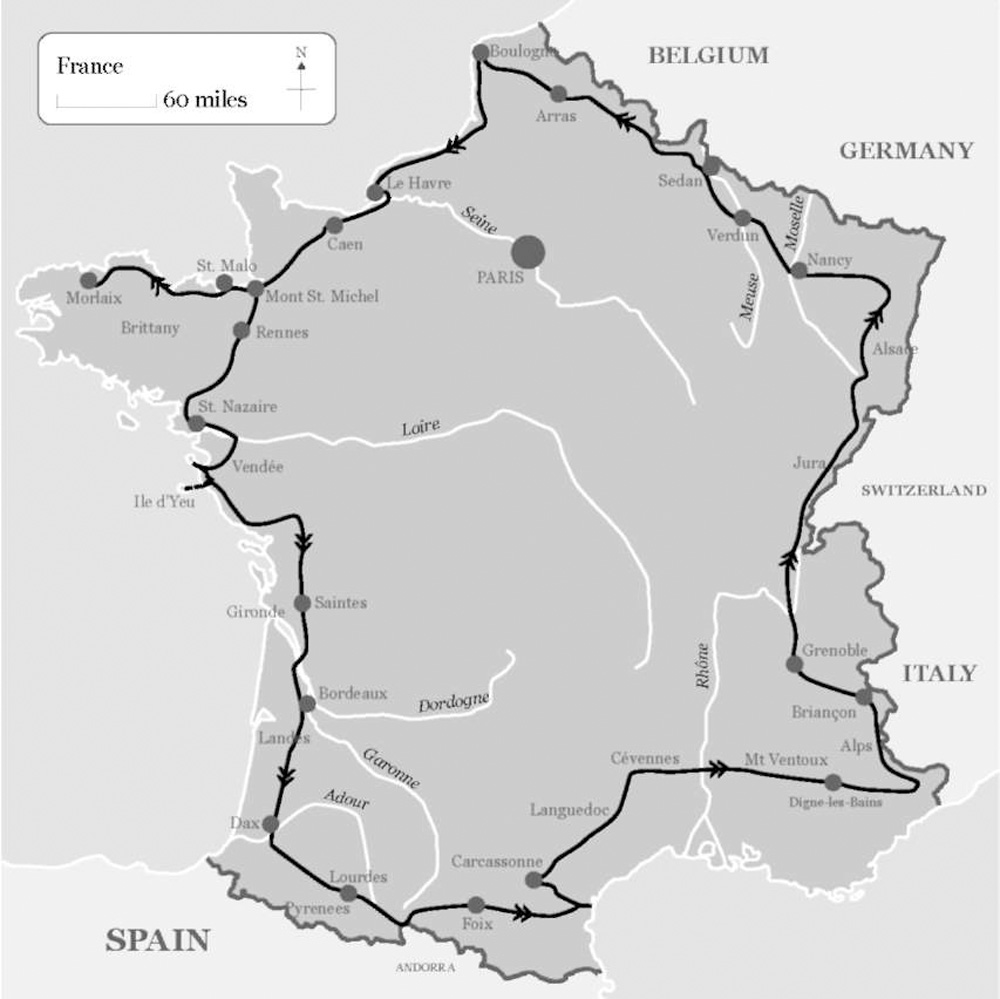

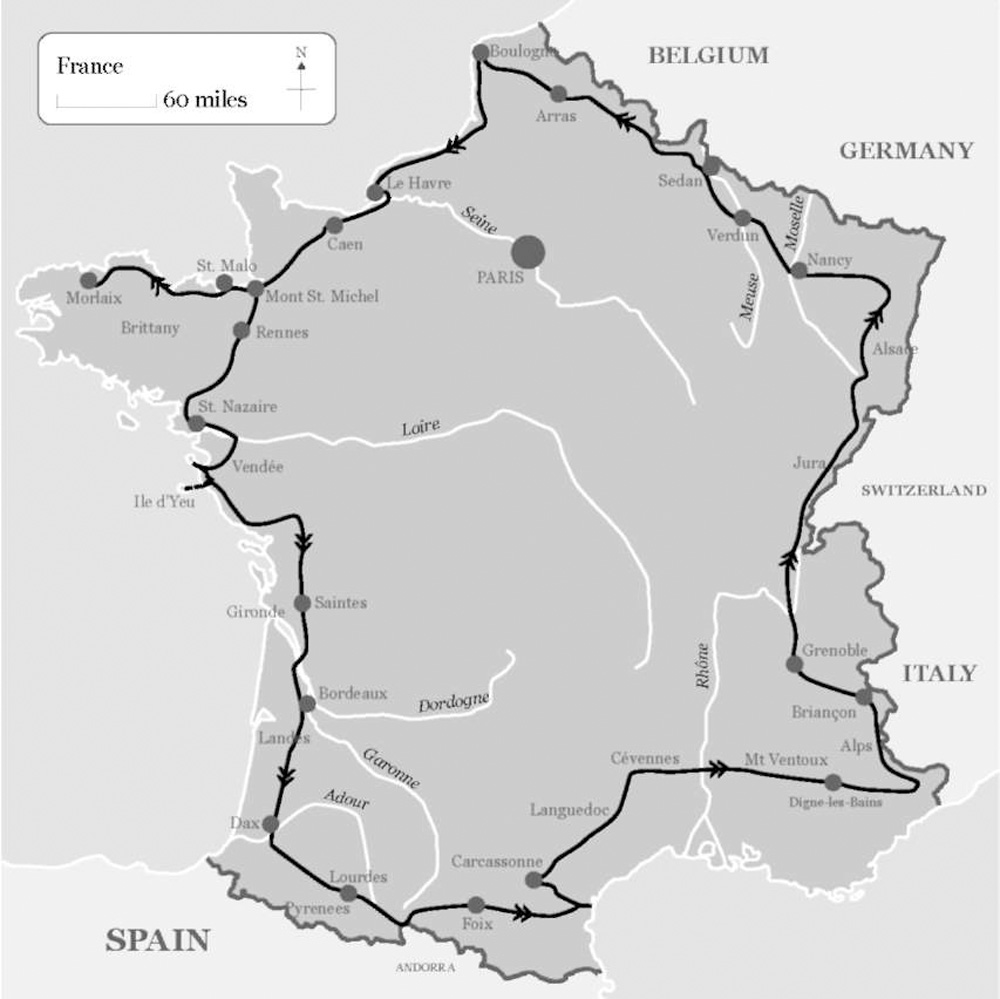

The French sometimes refer to their country as a hexagon, most frequently in the weather forecast. If you look at France on a map it has a six-sided symmetry, albeit with many lumps and bumps. My walk followed the shape of this hexagon more or less, hence the title (apologies to Corsica). I did, however, allow myself a bit of licence. For example, I did not complete the Pyrenean trail (GR10), preferring to visit the Cathar country in the east and the Barn in the west. I stuck to the mountains behind the Mediterranean coastal resorts. I left the Alpine trail (GR5) at Brianon to take in the crins, Grenoble and the Chartreuse. I followed the crests of the Vosges rather than walk along the Rhine.

I completed my walk in a number of stages of around a months duration. After each one I returned home for a rest and then resumed where I left off. Family demands prevented me completing my project as quickly as I would have liked. I covered half the total distance of 4,000 miles in one year and finished the remainder over the following two. My wife Lizzie accompanied me forty per cent of the way and friends joined us for a few days from time to time.

I wanted to have plenty of chances to talk to French people. This I certainly managed to do. I spent at least three hundred days in France and the French I met came from every walk of life. I prefer hostels, refuges and guest houses where you eat with other walkers and can chat far into the night. I made a lot of French friends whom I have visited since I finished my walk. There are advantages to walking alone. I notice things around me more when I am not talking to a companion . I walk at my own pace and stop whenever I want. I talk to more strangers when I do not have ready-made company.

Next page