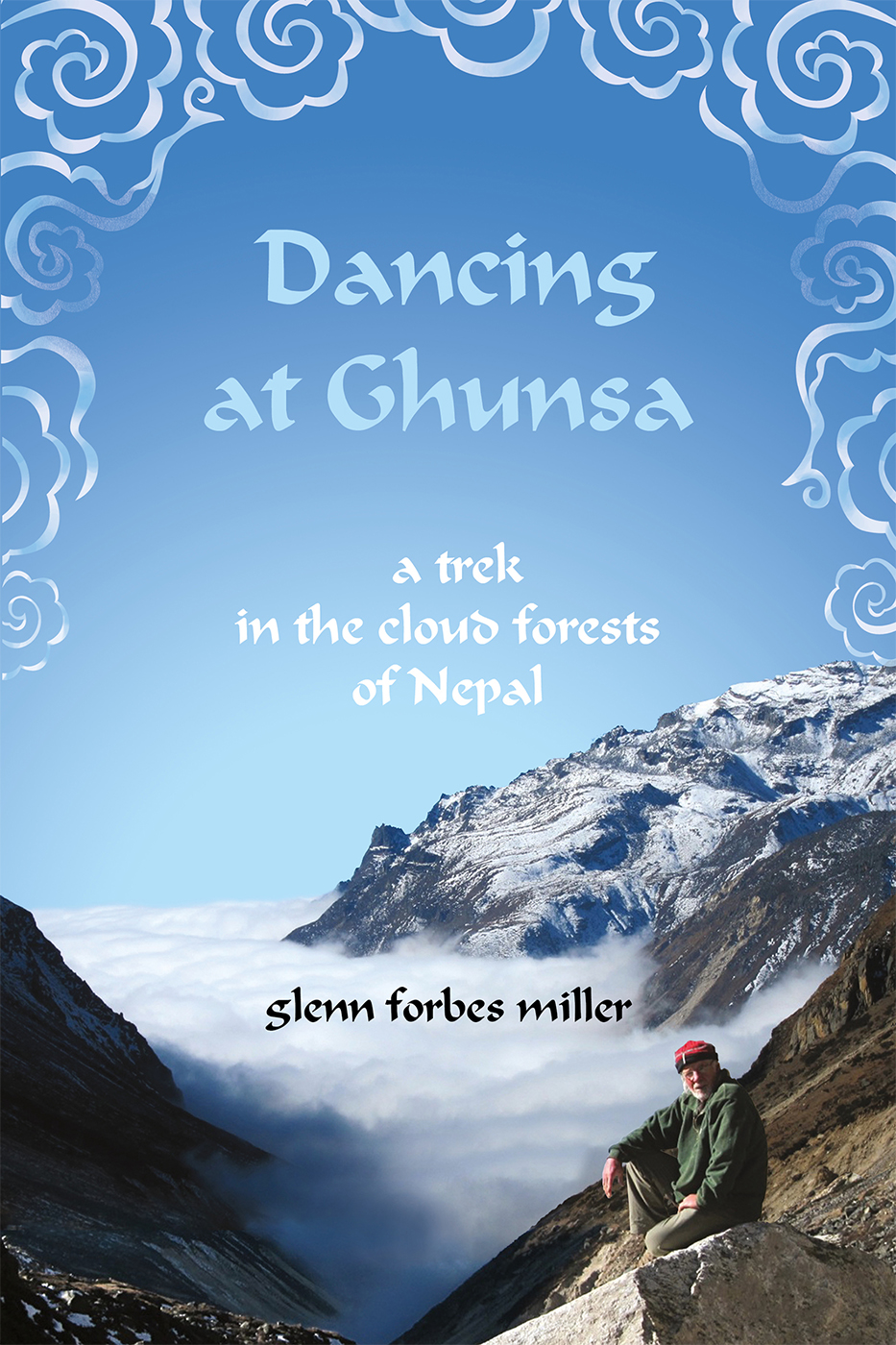

Dancing at Ghunsa

Dancing at Ghunsa

a trek in the cloud forests of Nepal

glenn forbes miller

GENERAL STORE PUBLISHING HOUSE INC.

499 OBrien Road, Renfrew, Ontario, Canada K7V 3Z3

Telephone 1.613.599.2064 or 1.800.465.6072

http://www.gsph.com

ISBN 978-1-77123-065-0

Copyright Glenn Forbes Miller 2014

Cover art, design: Magdalene Carson

Published in Canada

No part of this book may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted in any form or by any means without the prior written permission of the publisher or, in case of photocopying or other reprographic copying, a licence from Access Copyright (Canadian Copyright Licensing Agency), One Yonge Street, Suite 800, Toronto, Ontario, M5E 1E5.

Library and Archives Canada Cataloguing in Publication

Miller, G. Forbes, 1945-, author

Dancing at Ghunsa : a trek in the cloud forests of Nepal / G. Forbes Miller.

Issued in print and electronic formats.

ISBN 978-1-77123-065-0 (pbk.). --ISBN 978-1-77123-148-0 (epub).

--ISBN 978-1-77123-149-7 (mobi). --ISBN 978-1-77123-150-3 (ebook)

1. Kanchenjunga (Nepal and India) Description and travel.

2. Mountaineering Kanchenjunga (Nepal and India). I. Title.

GV199.44.K36M55 2014 796.522095496 C2013-908181-X C2013-908182-8

Paso con lenitude, como quien viene de tan lejo no espera llegar.

I walk slowly, like one who comes from so far away he doesnt expect to arrive.

Boast of Quietness by Jorge Luis Borges

Contents

there

were no mirrors

and but for a few photographs

I was not there

we passed invisibly under the sun

slept silently under

the cold alphabet of stars

Time befriended us

climbing high sleeping rough

moment by moment

and when the clouds cleared

we saw what we could see

there is where I wanted to go

there is where they took me

had there been a mirror

I might have seen our shapes

labouring over the landscape

and thought to document our going,

for a hard time I had of it

(my companions fared better)

yet each day dawned with promise

and each evenings fire

was warm with cheer

1

walk with me a while

I have to stop here for a bit... whooo... get my breath back... these markings on the bedrock here... glaciers made them... and the dew on the lichens... last nights hoarfrost that the sun has purged... O my goodness... look, up there, circling, thats a lammergeier, a vulture on the lookout for mole, marmot, marten, fox... vole, hare... and down there on the plain... those are yaks grazing, and that bent-over figure is gathering up yak dung. Now look to the farthest reach of the plain and you can just make out my orange tent pitched beside Ongyas home, six buildings in all, all made from gathered fieldstone and thats all there is to Lhonak. Not long ago, this entire valley was under glacial ice.

Just beyond Lhonak is a grey plain, a glacial deposit of small stones that once were great boulders transported by the Kanchenjunga Glacier and pulverized into fist-sized rocks. Look past the plain thats sand, an ancient seabed, not pulverized lithic grains but the fine, white sand of a sea floor raised up fifty million years ago when the Indo-Australian plate subducted the Eurasian plate and thrust up the Himalayas. Beyond the sand, where the valley terminates, are those braided gullies of moraine and that bluer-than-blue sky.

Off my left shoulder is a trough of glacial ice 100 metres wide and crusted over with moraine, an image so far outside my own ken that I had to ask Lal just what it was I was looking at: It resembles an aerial photograph, the kind that flattens to a grammar of light and shadow all the features of a landscape in this instance, horns, artes and mogul-like domes called sun cups, all of which terminate down there at Lhonak in a barren zone where its meltwater trickles from beneath the ice mass to become glacial streams that drain into the Ghunsa River, which in turn roars down the Lhonak Valley to Ramtang, Kambachen, Ghunsa, all villages we have passed through on our way up. Look about you: Very old land. Fifty-million-year-old real estate: location, location, location. The view enchants, but it is a desolate patch of land, even in the warmth of this apple-cider sunshine.

I would not farm it, opined the captain to Hamlet about a similar insignificant patch of land that Poland and Norway were warring over. Nothing could be farmed here, either, not even by the gallant captain, for nothing but the meanest of grasses, lichens, and alpine flowers subsist here in the thin soil, wind, and cold: gentiana, mountain heather, edelweiss, cinquefoil, primula, saxifrage, thistle, some form of onion, and blazing tangerine-coloured lichens growing on the boulders and stones, sedimentary rocks mostly, chert, siltstone, limestone.

Look. This is an ammonite fossil, a primordial mollusk incised by time into this fleck of limestone, its shell segments involuting like a rams horn. It was once an invertebrate sea creature that was thrust up these sixteen thousand feet from a sea so primeval the continents as we know them had not yet formed: the Tethys Sea.

A covey of snow pigeons feeds on submontane scrub: dwarf maples, red barberry, recumbent juniper, yellow potentilla, dwarf rhododendron, cotton Easter, and sea buckthorn, readied now for winter, having dropped their seeds and flowers and shrunk to a spiky furze. One pigeon flares up from the furze and then all arrow after it in a silent flocking to feed on the higher scree. The muttering of pigeons and the rustle of the dry wind in the broom are the only sounds.

These Himalayan wastes enchant me. Perhaps I am autochthonous here, not a visitor, but an aboriginal, a son of the mountains come to reclaim an ancient patrimony. I feel at home here as some might feel a kinship with the sea. Standing stock-still, trying to suspend the moment, I close my eyes to frame a memory of the place and just breathe... breathe in the plenitude of this time in this place (a plenitude imprinted there still): so pristine, individuated, unadulterated, synergic, and fragile, yet thriving.

Looking back at Lhonak.

This is a moment... a moment outside of myself, one far wide of my ego, when you feel a oneness with the earth and the sky and what lies beyond, a moment that glimmers with inwit.

Here, every thing is everything.

2

the paradox considered

Every thing is everything? What does that signify apart from its own cleverness? Let me make the case for the paradox.

Being in the moment has something to do with it: being mindfully aware of what is happening inside our own heads. Our minds are endlessly busy receiving and processing a chattering stream of sensory data, constantly updating neuronal memory and managing desire, forethought, and volition. Much of our waking time, though, is spent reflecting upon the past and daydreaming about the future, neither of which is real. Only the present moment is real. Buddha says, The mind is everything. What you think you become. So to be more humanly aware, Buddha suggests, we need to have intentional control of our minds to be more in the moment. That, as I said, has something to do with the paradox. So does spirit.