This ocean of the world is hard to cross:

its waters are very deep.

Kabir

When the uncertain future becomes the past,

the past in turn becomes uncertain.

Mohsin Hamid, Moth Smoke

Je est un autre.

Arthur Rimbaud

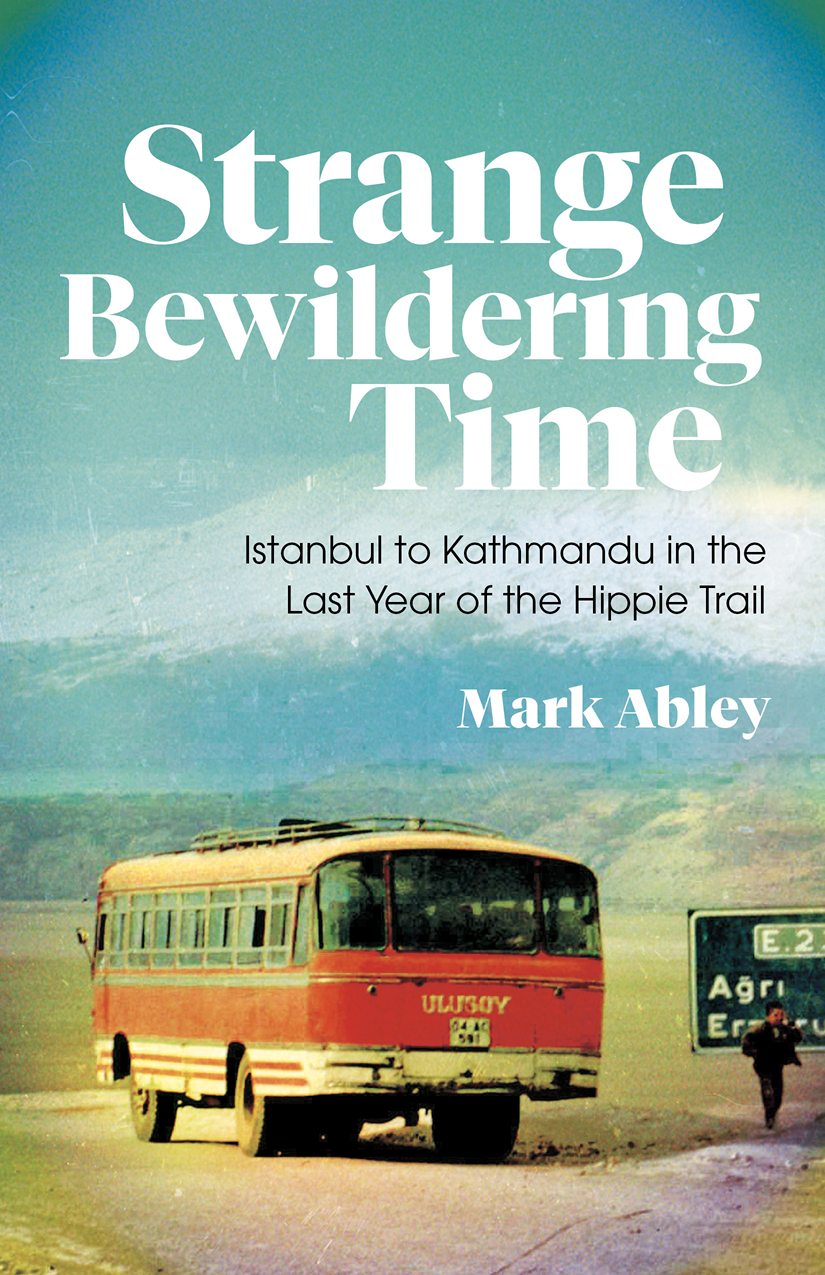

1.

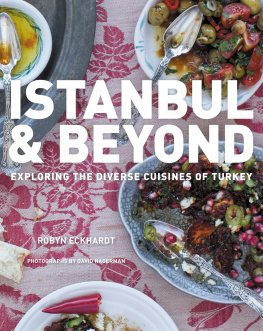

Turkey

You wouldnt want to know

Clare and I hugged our partners goodbye at Oxford station. The time had come. Trapped in a clump of commuters with neckties and briefcases, I tried to look confident; Clare succeeded in looking determined. Doubts battered me. What was I doing? How could this trip, any trip, justify a wilful absence from love?

I heaved my navy blue backpack and sleeping bag onto my shoulders and found a pair of seats on the train. It was a cold grey day: along Port Meadow the morning river drank up the sky. Oxfords intricate pattern of spires and domes retreated all too fast. A woman sitting near us spent the hour to London Paddington poring over a copy of The Times a copy that was four weeks old. In Aprils infancy, the beeches and oaks by the Thames stood bare. London was a Tube-smelling blur. Twice, without thinking, I stretched out to hold Clares hand and managed to pull back in time.

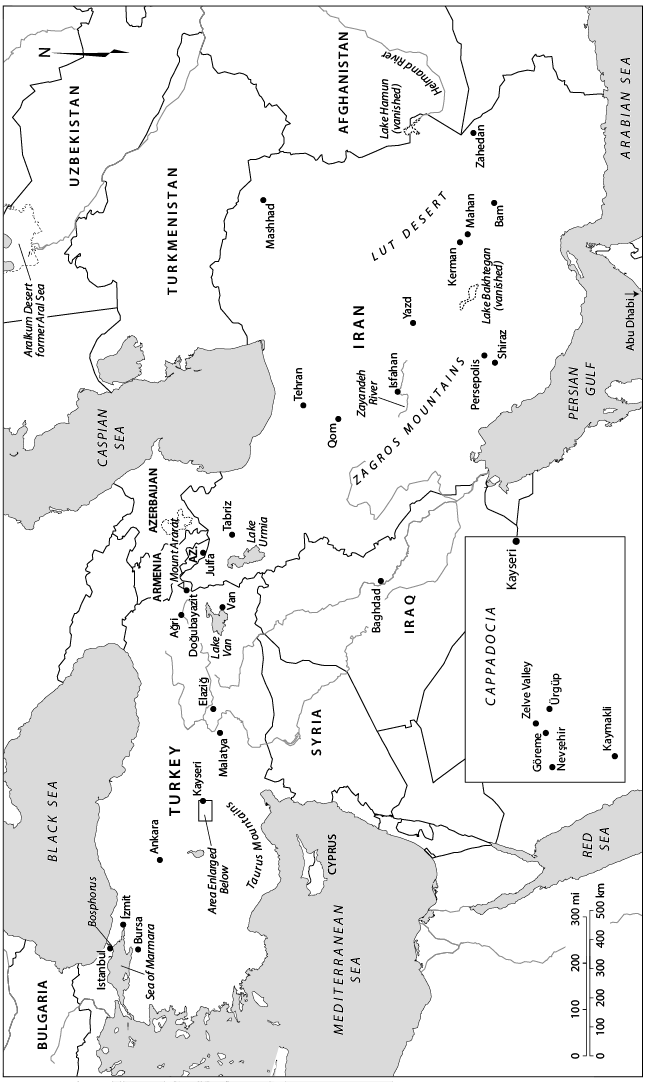

We crossed the English Channel by ferry and climbed aboard a waiting train in France. A few years earlier I would have felt overjoyed to alight in the country; now it scarcely registered in my mind. Un croque monsieur, sil vous plat dreams of India and Nepal kept flickering behind my eyelids et un caf au lait. I could imagine the sleekly flowing Ganges and the soaring Himalayan peaks we hoped to see after two months on the road. I could not imagine the chained bear, the belly-dancing teenagers, the drunk driver, or the truckloads of riot police we would encounter in the first two weeks.

France gave way to Switzerland. Hours later, the train having chugged into a town in northern Italy, a passenger raised a window, stretched out an arm and snapped off a sprig of pine. He set it down on a narrow shelf its sharp, fresh scent filled the compartment until we rolled to a halt beside the Grand Canal. The champagne splendours of the Orient Express, with its murders and sofas and wood-panelled sleeping cars, were no more: indeed, a direct Paris-to-Istanbul train had made its final run a year earlier. I didnt mind. Before heading east again, we gave ourselves a night and day in the amphibious pomp of Venice. A pair of stone lions that we noticed at the entrance to its ancient shipyard commemorate a victory over the Ottoman Empire through the long centuries when the city was a sovereign republic, it fought seven wars against the Turks and launched a disastrous crusade. Like so much of Europe, Venice had defined itself in opposition to Islam and the Orient.

I hadnt bothered to obtain a Yugoslav visa, assuming it would be simple to buy one on the next leg of the journey. But an hour shy of midnight, after the train shuddered to a halt at Italys eastern border, a beetle-browed guard seized my Canadian passport and held on to it.

This way, he said. Come.

I stepped down into a chilly darkness. The guard strode off between two sets of railway tracks past the front of the train. He disappeared into a small, dimly lit building, leaving me alone outside. I stood there, conscious that my ticket was still in my backpack and my backpack was still on the train. Time slipped by. A bemused Australian girl on her way to a Greek island joined me at the door. Our talk lapsed into silence. A few other passengers arrived, their voices clearer than their faces in the moonless night. What if the train moved off without us?

But once the door creaked open, the visas were distributed quickly and free of charge. My relief felt as vast as Europe.

I repaid the Yugoslav officials by smuggling a new pair of jeans into their country. Clare did the same. A couple from Belgrade asked us to do this: they would earn a handsome profit if we helped them sidestep the countrys import laws. Paul, a young artist from London with a sketchpad and a determined gaze, found room to stash away two pairs of jeans and a pocket calculator. The Yugoslav couple beamed at us all.

Was the train muscling through Slovenia or Croatia as a grey dawn broke? In 1978, who outside the Balkans thought a question like that could ever matter? Warfare in eastern Europe surely belonged to the past. For an hour the train shadowed a copper-coloured river, magpies and hooded crows flapping heavily away toward a chain of burly mountains. A shepherd holding a crook oversaw a flock of dark-faced sheep. The massive high-rise blocks of Belgrade loomed into sight; the smiling Yugoslav couple wobbled out of our compartment and staggered off the train, their arms full of jeans and other Italian purchases. I dozed through the limestone hills of eastern Serbia and woke to a fox, its mouth full of some small bird or mammal, standing in a muddy field and watching the train pass. The trees wore a sumptuous formal attire of white and pink blossoms.

At the Bulgarian frontier, the guard inspecting our documents turned out to be a football fan. He picked up Clares British passport: England! Bobby Charlton. Bobby Moore. He must, judging by his looks, have been a teenager in 1966 when an English squad won the World Cup for the first and only time. Geoff Hurst, I said. Barely glancing at my Canadian passport, he replied: Gordon Banks. Damn, who else was on the team? I rummaged the depths of my memory Martin Peters! The guard was relentless: Alan Ball. I lifted my empty hands. He nodded his head in triumph. So much for the Iron Curtain.

Border followed border. After a long wait at the final one, we crossed into Turkey and a young, clean-shaven lab technician took an empty seat nearby. He came from a town in the recently divided island of Cyprus a Turkish invasion in 1974 had sliced it in two, preventing the entire nation from being forcibly incorporated into Greece. Clare and I had no Turkish lira. Discovering this, Emir bought us each a sesame-seed pastry. For him, the price of a secure homeland was the absence of a country: his passport, though issued by Turkey, had a blank in the space marked nationality. This hampered his ability to travel. Hed married an Englishwoman, he told us, but when he arrived at the port of Dover to meet her family, the British authorities refused to let him in.

Why? he asked. She is my wife.

Clare and I made sympathetic noises.

Emir wanted to talk. Moving on from the tale of his own life, he recounted a story that has circulated in Turkey, Iran, and central Asia for hundreds of years. You can see the hero, Nasreddin Hodja, as a holy fool, a trickster, a wise man, or all three. He is a mullah a highly unorthodox one.

In the story, a wealthy neighbour named Aslan tries to play a mean joke on Nasreddin. The mullah is praying for money he and his wife, Fatima, survive amid empty shelves when Aslan delivers a bagful of gold coins. Nasreddin thinks, or pretends to think, that the gold is a payment from God. But Aslan soon demands the money back, and he takes the mullah to court. At this point, Nasreddin devises a plan to outwit his neighbour. And a judge, having heard both men speak, tells the mullah to hold on to the gold.

Thats how the story usually goes. Yet thats not quite what Emir told us as the train rattled across the plains of western Turkey. His Nasreddin was a proud Turk, the rich neighbour a businessman from Athens.

So you see, Emir said, the Turk keeps the money.

He flashed a broad smile I saw a glint of metal between his lips. A timeworn Nasreddin story had become a parable of national honour.

Next page