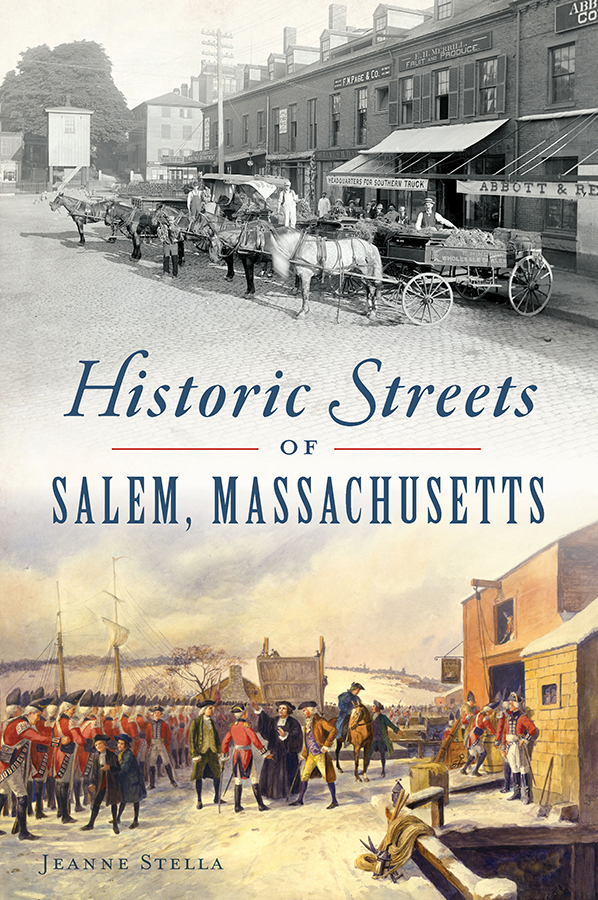

Published by The History Press

Charleston, SC

www.historypress.com

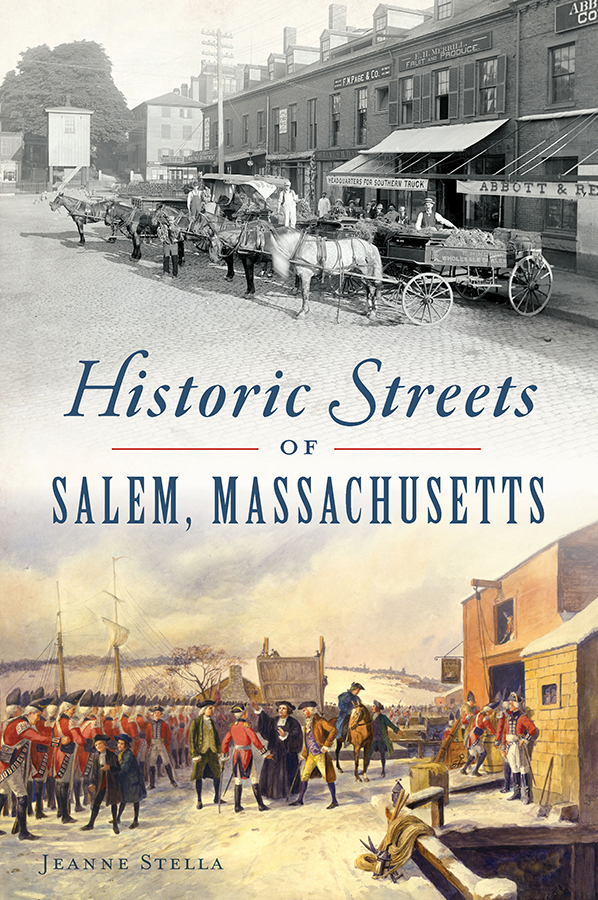

Copyright 2020 by Jeanne Stella

All rights reserved

First published 2020

E-book edition 2020

ISBN 978.1.43967.007.1

Library of Congress Control Number: 2020930477

print edition ISBN 978.1.46714.333.2

Notice: The information in this book is true and complete to the best of our knowledge. It is offered without guarantee on the part of the author or The History Press. The author and The History Press disclaim all liability in connection with the use of this book.

All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced or transmitted in any form whatsoever without prior written permission from the publisher except in the case of brief quotations embodied in critical articles and reviews.

To The Salem News, which first published the original version of these street stories on the editorial page as letters to the editor from 2008 to 2018, and especially to the memory of Nelson K. Benton, former editorial page editor whose friendship and guidance I will always treasure.

Contents

Introduction and Acknowledgements

I would like to acknowledge my good friend Ryan W. Conary, who provided technical assistance and took many of the photos you see on these pages.

One of the main questions people ask when they write for online information: Is Salem a real place? My answer would have to be, I hope so, because Ive lived in Salem for fifty years, since 1968.

I am connected to Salem through its witchcraft history: my ancestor Mary (Perkins) Bradbury was one of the unfortunate people condemned for witchcraft, but she fortuitously escaped from the Salem prison where she was being held to await execution by hanging. The court record shows that she made her escapeby what means is unknown.

A long look back into my ancestry led me to historical pursuits, and with encouragement from The Salem News, which first published my street stories as letters to the editor, I became a local historian. With my background as a tour guide in a historical setting, I have presented each street in this collection as a historical tour.

The maps and atlases (courtesy of the Southern Essex Registry of Deeds) and photographs were contributed and arranged by historian and photographer Ryan W. Conary, who donated his time and talent to help engineer this work and make it a reality.

I hope you enjoy reading and experiencing these street tours as much as I did writing them.

Jeanne Stella

Salem, Essex County, Massachusetts

I.

OVERVIEW AND HISTORICAL NARRATIVE

THE FIRST YEARS

If you were a Puritan in seventeenth-century England, chances are youd be looking for a new place to live. A group of English citizens, known as Puritans, wanted to purify the church of its rituals, to return to a simple style of worship. These people left England and came to America for freedom to set up a church that reflected their principles.

The year 1626 saw a small group of English fishermen at Naumkeag, the fishing place, named after the Naumkeag Indians who had planted here. The place would, in three years time, be known as Salemfrom shalom, the Hebrew word for peace. The group had tried a settlement at Cape Ann (Gloucester), but problems there had caused them to abandon that location in favor of one better suited to their purpose.

Roger Conant, leader of this group, originally came from East Budleigh in the southwest part of England. A salter by trade, Conant temporarily served as governor. While there is no complete agreement among historians regarding the names of those who accompanied Conant, most lists include John Balch, John Woodbury, Richard and John Norman, William Allen, Peter Palfray and Walter Knight. These men and their families were called the Old Planters, but it was fishing, not farming, that became the mainstay of the colony and the industry that built the town.

At first, there were no streetsall travel was by water. The arrival of Governor John Endicott in 1628 brought progress: streets were laid out, and the town was divided into house lots. The first street laid out by the new governor was Washington Street. Running between the North River and the South River as it did, it gave a commanding view of both and offered protection to the colonists. They could now see who was coming to dinner.

Paths were made along the waterfront. These first paths were called highways, and streets with names were later laid out over them. Paths along the waterways were crooked because they followed the outline of the river. Front Street, then known as Wharf Street, was an original river path.

According to Salem historian Sidney Perley, Essex Street was one of Salems first streets. Historian James Duncan Phillips believes it was once an Indian trail.

THE WITCHCRAFT DELUSION

Only sixty-six years after Salems founding, an unusual and unfortunate chain of events in Salems history began to unfold. In the winter of 169192 in Salem Village (what is now Danvers, Massachusetts) a group of girls gathered to hear strange tales told by Tituba, a West Indian slave of Reverend Samuel Parris, minister of the village church. The girls kept these meetings secret. They knew their religious teaching would forbid them to listen to Titubas occult stories.

Two of the girls began to have fits, contorting themselves into positions that would, under any normal circumstances, be impossible to affect. They also made animal noises and displayed other bizarre forms of behavior. Before long, all of the girls were having fits.

Diagnosed by the village doctor as bewitched, they were asked who bewitched them. After persistent questioning, the girls named three women, including Tituba. The girls claimed to have spectral sightthey could see the ghostly shapes of those they had accused, tormenting and afflicting them.

It was believed that a witch could make a pact with the devil, giving him permission to appear in the witchs shape, to cause harm to others. The witch would then seal the pact by signing the devils book:

Many at that time seemed to believe, that the witches actually signed a material book, presented to them by the devil, and were baptized by him, in which ceremony the devil used these words: Thou art mine, and I have a full power over thee! Afterwards communicating in an hellish bread and wine , administered unto them by the devil. This was denominated a witch sacrament. To which communions, the witches were supposed to meet upon the banks of the Merrimack River, riding there upon poles through the air.

The History of Rowley , Thomas Gage, p. 178

(Boston: Ferdinand Andrews, 1840)

Thompkins Harrison Matteson, Trial of George Jacobs, August 5, 1692, 1855. Oil on canvas. 39 x 53 inches (99.06 x 134.62 cm). Peabody Essex Museum, Gift of R.W. Ropes, 1859. 1246. Photo by Mark Sexton and Jeffry R. Dykes, courtesy of Peabody Essex Museum.

The first to be accused of practicing witchcraft were women, but as the situation escalated, men figured in the number. Witches were found in surrounding towns. At the trials held in Salem, both men and women were convicted on the basis of spectral evidence. In all, more than two hundred people were accused, nineteen people were hanged and one was pressed to death for refusing to enter a plea.

Next page