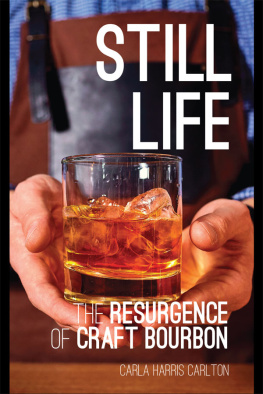

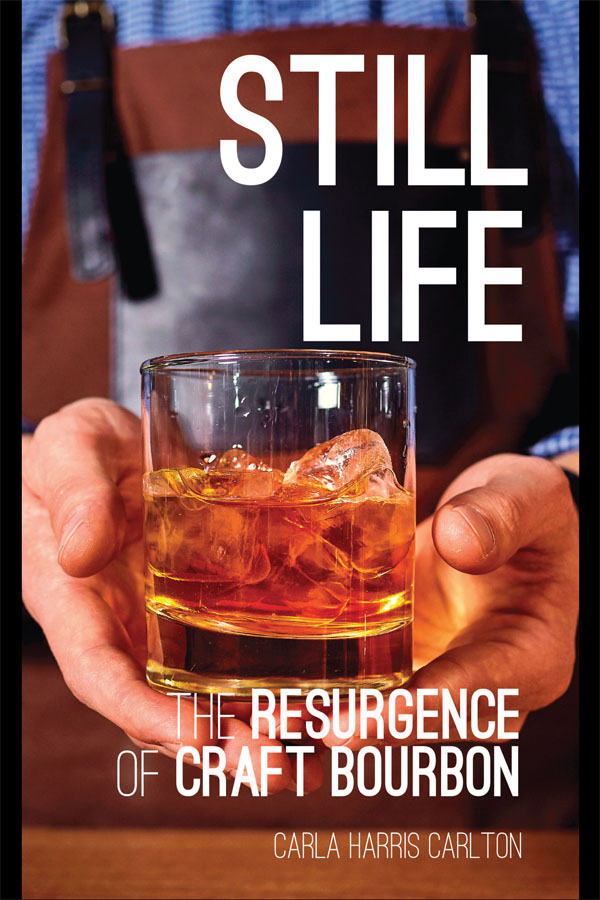

Still Life:

The Resurgence of Craft Bourbon

COPYRIGHT 2017 by Carla Harris Carlton

ALL RIGHTS RESERVED.

No portion of this book may be reproduced in any fashion, print, facsimile, or electronic, or by any method yet to be developed, without express permission of the copyright holder.

For further information, contact the publisher:

CLERISY PRESS

An imprint of AdventureKEEN

2204 First Avenue S., Suite 102

Birmingham, AL 35233

clerisypress.com

Cataloging-in-Publication Data is on file with the Library of Congress.

eISBN: 978-1-57860-577-4

Distributed by Publishers Group West

Printed in the United States of America

First edition, first printing

Editor: Kate Johnson

Project editor: Ritchey Halphen

Cover design: Travis Bryant

Text design: Steve Sullivan and Steve Jones

Craft Tour map: Scott McGrew

Cover photo: Studio Romantic/Shutterstock

Interior photos: As noted on page

Frontispiece: The sun shines bright on Kentucky bourbon at Corsair Distillery in Bowling Green, Kentucky. (Photo courtesy of the Kentucky Distillers Association)

For my family

TABLE OF CONTENTS

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

I AM GRATEFUL to all of the craft distillers who welcomed me into their distilleries and shared their storiesoften while rinsing a barrel or autographing a bottleand to Master Distillers Jimmy Russell (Wild Turkey), Jim Rutledge (formerly of Four Roses, now of J. W. Rutledge Distillery), Harlen Wheatley (Buffalo Trace), and Charlie Downs (Heaven Hill), who were generous with their time and their expertise.

I also owe a debt of gratitude to the Kentucky Distillers Association for providing information, guidance, and photographs, and to the American Distilling Institute for allowing me to attend its 2015 conference in Louisville and for providing statistics on craft distilling nationwide. Finally, I give my heartfelt thanks to my wonderful familymy mom and dad, Joyce and Carl Harris, whose lifelong encouragement made me believe I could write a book; my husband, Chad, who kept me sane during the process; and our children, Harper and Clay, who trekked all over the Commonwealth of Kentucky with me and know more about bourbon than anyone under the age of 21 should. Cheers to you all.

INTRODUCTION

IN THE EARLY 1930s, a pickup truck pulled up to a small cabin near the Western Kentucky town of Golden Pond just as the sun was rising, and a man climbed in. He carried with him a pump gas blowtorch, a soldering iron, and some copper sheets. The driver took the man to a small clearing deep in the woods, let him out, and drove away.

That evening, the driver returned, collected the man, and took him home. And so it went for the rest of that week. On the last evening, the man smiled and revealed the results of his handiwork: a copper moonshine still, ready to be fired up. Rectangular and flat-bottomed, the wagon-bed still would be easy to dismantle and throw into the back of the truck on short noticean important feature when government revenue agents could show up at any time.

During the dark days of Prohibition and even after, when hard liquor was hard to come by, Casey Joness moonshine was in high demandbut it was his still-building skill that was most prized. By some accounts, he crafted as many as 150 stills over the years. Its said that he even built one across the Cumberland River from the Kentucky State Penitentiary at Eddyville.

Arlon Casey Jones: a man and his still (Photo: Chad Carlton)

My grandfather was probably one of the biggest still builders in Golden Pond there ever was, says Arlon Casey Jones. Everybody wanted him to build their stills if they could get him.

Eventually, though, the feds got him instead. He spent two years in prison in Virginia and then lived with Arlons family for a time. He never talked much about his past with his grandson, but Arlon heard tales from cousins who had also run moonshineand had also done time. (Arlons father, Robert Jones, escaped prison only by joining the Marines.)

Decades later, Arlon Casey Jones is running his own copper moonshine still in Western Kentucky. He built it himself, patterning it after the last still his grandfather ever made, and he uses the old family recipe. He even took Casey as a middle name.

Thirsty travelers follow a winding driveway off a two-lane road on the outskirts of Hopkinsville to a small, unassuming building next to his house, where they can have a sip of shinemaybe straight off the still, if theyre luckyand buy a bottle or two. But theres one big difference between this Casey Jones operation and his grandfathers: Arlon Casey Joness distillery is completely legal.

Today, its not the quest for the unattainable that draws consumers to small operations like Casey Jones Distilleryits the thirst for something new and different. And a rapidly growing number of entrepreneurs are seizing the opportunity to make their own spirits and reclaim a part of distilling history that Prohibition nearly wiped out.

{ Just A SIP }

Before Prohibition, there were 183 operating distilleries in Kentucky; fewer than half survived.

In early America, just about every farming family distilled its extra grain, often using the resulting spirits as a form of money. As the country became more industrialized, small commercial distilleries became the norm. Prohibition closed all but six, which were allowed to produce medicinal spirits. At that point, moonshiners were the only craft distillersalthough, since most of them sold high-octane spirits right off the still, their customers would probably dispute the use of the term craft. Many small distilleries never reopened following Repeal. Others consolidated and acquired the rights to use the brand names of many of the former operations. Eventually, almost all distilled spirits were produced by high-volume mega-distillers.

Ironically, it was these mega-distillers that helped get the little guys back into the business. In the 1990s, to lure drinkers back to the brown spirits that had fallen from favor, major distillers created the super-premium category: limited-edition bourbons at higher prices. The success of this marketing effort opened the door for entrepreneurs to produce low-volume, high-priced spirits that liquor stores and bars would stock.

You might hear them called craft distillers, or microdistillers, or artisanal distillers. But those are all just different names for the same thing: independent, small-scale spirits-making enterprises. And their numbers have increased by more than 1,000% in the past decade.

Microdistillers Pour It On

IN 2003, WHEN Bill Owens founded the American Distilling Institute (ADI), a trade group, there were 68 microdistilleries in America. Now there are about 1,300, and hundreds more are under construction.

There is no official definition for craft distillery. The ADI says a craft distiller is one whose annual sales are less than 100,000 proof gallons. (A proof gallon, which is used to calculate taxes owed, is 1 liquid gallon of spirits that is 50% alcohol at 60F.) Under the membership rules of the American Craft Spirits Association (ACSA), another trade group, membership levels begin with those who produce up to 1,000 proof gallons per year and are capped at 750,001 proof gallons.

Next page