Neil McKenna 8, 100,122 Sandra Lipton 27, 28, 29, 30, 37, 38, 44, 54, 55, 57, 61, 62, 69, 70, 75, 79, 81 Daniel Bexfield 31, 71, 82 Bryan Douglas 32, 67, 76 Esford Pty 116 Mike Lemke 177 For their co-operation and assistance we would like to thank the following organisations: The British Museum, Christies, Grosvenor Museum, The London Library, Phoenixmasonry, Sothebys If the publishers have unwittingly infringed copyright in any illustration reproduced, they will gladly pay an appropriate fee on being satisfied as to the owners title.

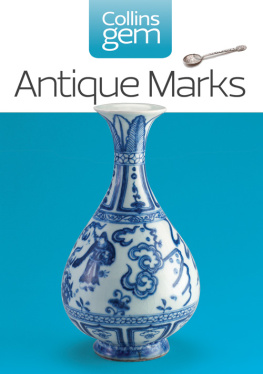

Do you ever attend car boot sales or browse in antique shops in search of bargains? Have you ever wished you knew more about your grandmothers silver spoon, or that old piece of china which has been around your home for so many years? Do you envy the experts ability to identify and date such fascinating hand-me-downs? If the answer to any of these questions is yes, then

Collins need to know? Antique Marks is for you.

Spanish chalice with repouss and chased decoration, 1670

Spanish chalice with repouss and chased decoration, 1670 The book begins with a clear and thorough guide to the hallmarks stamped on British gold and silver since the Middle Ages, and those now found on platinum. The precious metals section continues with pages exclusively devoted to American, African and Asian gold and silver; a historical review of leading goldsmiths and silversmiths; and a glossary of the terminology currently used by the professionals. The second section of the book looks at the quite different marks to be found on Old Sheffield Plate. A representative selection of pewter makers marks is provided next, as an introduction to these once very common household wares.

This section closes with an examination of some traditional techniques used in working with precious metals. The final section of the book surveys the vast range of marks to be found on pottery or porcelain, both from Britain and the rest of Europe, and from China and Japan. There are also profiles of leading pottery and porcelain manufacturers; some background information on methods of ceramic construction and surface work; and a glossary of ceramic terminology. While the depth of knowledge of the true expert requires years of experience in studying and handling antiques, Collins need to know? Antique Marks will provide you with the instant means to interpret the marks that are often crucial in assessing antique objects.  Nuremberg faence jug, early 18th century

Nuremberg faence jug, early 18th century

Precious metals are those materials favoured by craftsmen for making objects of beauty: gold, silver and in recent times platinum. The objects made in Europe were and are under the control of each countrys government.

Marks were struck on some part of the object to identify its date of manufacture, the place of origin and its maker. This section contains British hallmarks from the 16th century, location marks of government assay offices and a selection of British craftsmens marks.

Silver and gold are prized for their useful and attractive properties. Gold was one of the first metals to be discovered. Being soft and easy to work, colourful, bright and resistant to corrosion, it was ideal for jewellery and other decorative objects. Its scarcity ensured that its value remained high.Silver is harder and less scarce than gold, and more widely used in everyday life.

Both have been mined in modest quantities in Britain since Roman times. Platinum was unknown in Europe until 1600. It only became available commercially in the 19th century, and has been regulated in Britain since 1975. It is mainly used for jewellery. Since 1 January 1975, a simplified scheme of hallmarks has been in use for British silver, gold and platinum, as directed by the 1973 Hallmarking Act.

mustknow The high value of these three metals makes it essential to have legally enforced standards of purity.

The craft of the silversmith has been regulated by Parliamentary Acts and Royal Ordinances since the late 12th century.

Pre-1975 hallmarks and what they mean

Under British regulations, any object made of silver or gold is stamped with various hallmarks to show when it was made, by whom, where it was made or tested for purity, and most importantly,how pure it is. The term hallmark is derived from Goldsmiths Hall, the guild hall of the London Goldsmiths Company, the body that oversaw the first assay marks in Britain. In 1300, the sterling standard was established at 925 parts of silver per 1000. No object could leave the craftsmans hands until it had been assayed (tested) and marked with a punch depicting a leopards head.

must know From 1478, a date mark was required to be struck, a letter of the alphabet that signified the year in which the piece was assayed.

must know From 1478, a date mark was required to be struck, a letter of the alphabet that signified the year in which the piece was assayed.

This made it possible to trace the Keeper of the Touch who had assayed a piece, in case of disputes as to purity. It now allows us to determine an accurate date for any piece of British plate. A duty mark depicting the head of the current monarch is found on plate assayed between 1784 and 1890, as proof that a tax on silver goods had been paid. The duty mark should not be confused with later commemorative stamps, which mark special occasions such as coronations and jubilees.

Marks of origin on British silver to 1974

The mark of origin identifies the town or city where an item was assayed. Since 1300, London has used the leopards head ().

An exception is the period 16971720, when the lions head erased ()was used, when the Britannia standard replaced the Sterling standard for English silver. At Edinburgh, the earliest Scottish assay office, the mark of origin has always been a three-towered castle (). Dublin has used a crowned harp () since the mid-17th century. Birmingham has long used an anchor (), and Sheffield used a crown () for many years. More marks of origin are shown later in the chapter. Sample marks of origin

Makers marks

Since 1363, silversmiths have had to stamp their work with a registered mark.

At first the custom was to use a rebus (for example, a picture of a fox for a silversmith whose surname was Fox) and initials combined in one mark. From 1697, makers had to use the first two letters of their surnames (a, b overleaf), but from 1720 initials again became the norm (c, d), sometimes with a symbol added (e, f). In Scotland before about 1700, makers commonly used a monogram (g, h), later replaced by plain initials (i). Some used their full surname (j). In the case of factories or firms (k), the makers mark is often called the sponsors mark. Sample makers marks aThomas Sutton, London 1711

aThomas Sutton, London 1711

Spanish chalice with repouss and chased decoration, 1670 The book begins with a clear and thorough guide to the hallmarks stamped on British gold and silver since the Middle Ages, and those now found on platinum. The precious metals section continues with pages exclusively devoted to American, African and Asian gold and silver; a historical review of leading goldsmiths and silversmiths; and a glossary of the terminology currently used by the professionals. The second section of the book looks at the quite different marks to be found on Old Sheffield Plate. A representative selection of pewter makers marks is provided next, as an introduction to these once very common household wares.

Spanish chalice with repouss and chased decoration, 1670 The book begins with a clear and thorough guide to the hallmarks stamped on British gold and silver since the Middle Ages, and those now found on platinum. The precious metals section continues with pages exclusively devoted to American, African and Asian gold and silver; a historical review of leading goldsmiths and silversmiths; and a glossary of the terminology currently used by the professionals. The second section of the book looks at the quite different marks to be found on Old Sheffield Plate. A representative selection of pewter makers marks is provided next, as an introduction to these once very common household wares.  Nuremberg faence jug, early 18th century

Nuremberg faence jug, early 18th century

aThomas Sutton, London 1711

aThomas Sutton, London 1711