The paper used in this publication meets the minimum requirements of the American National Standard for Permanence of Paper for Printed Library Materials Z39.481984.

INTRODUCTION

A Very Loud Amusement Park

BRIAN WALTER

A methodical man, John Shade usually copied out his daily quota of completed lines at midnight but even if he recopied them again later, as I suspect he sometimes did, he marked his card or cards not with the date of his final adjustments, but with that of his Corrected Draft or first Fair Copy. I mean, he preserved the date of actual creation rather than that of second or third thoughts. There is a very loud amusement park right in front of my present lodgings.

V. Nabokov, Pale Fire

THE FIRST MISTAKE I MADE with Donald Harington remains the most useful. Over lunch during our very first meeting, I asked him, in reasonably perfect innocence, So, what kind of projects are you working on now?

It was the fall of 1996, and I hadnt read any of his books yet. On this, my first trip to Fayetteville, I was seated across the table from Don and his wife in their deceptively expansive home, and I was just trying to be polite by lobbing him a flattering question. In my three decades of presumptuous existence, I had had the good fortune to dine with a number of fine fiction writers and poets who, like Harington, paid the bills with university teaching posts, and most of them, I had learned, produced scholarly and professional work along with their art. Project seemed like a safe term for anything my host might be working on.

Harington would have none of it. Leaning over the table, leaning into his response, leaningit somehow seemedright into me, the playfully offended writer retorted, Projects? I dont do projects. I write novels!

Anyone who ever met Harington will understand perfectly well why I went right home and dove into Ekaterina to repair a glaring omission in my education. What did it mean for this tall, stooping, white-haired manwith thick glasses, a voice thinned out by throat cancer, a ponderous hearing aid, and a breast-pocketful of index cards to write novels?

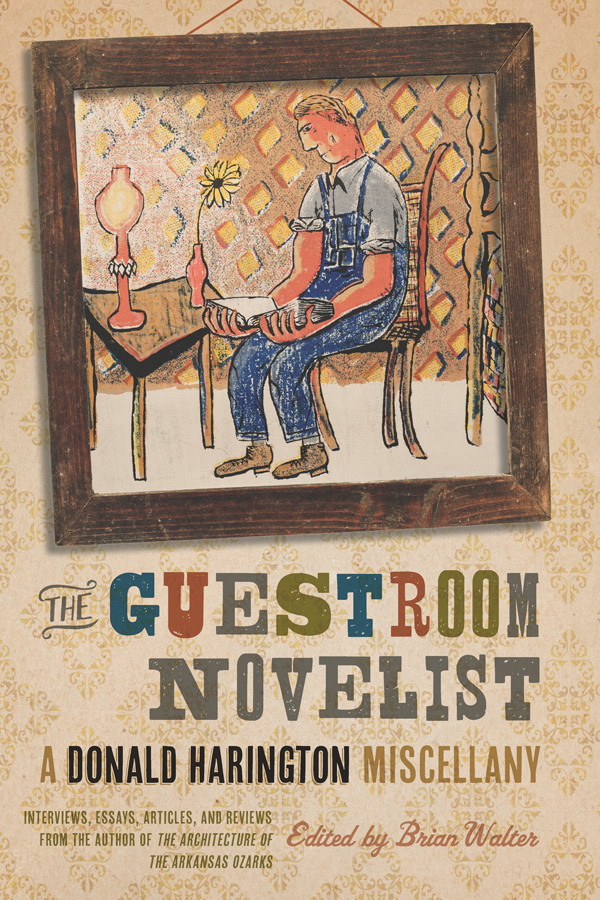

Over the course of the next thirteen years, Haringtons indignant declaration of his real vocation echoed and reechoed in my mind as I read my way through his corpus, corresponded with him, visited and hosted him and his wife, wrote articles and reviews about his novels, and, finally, interviewed him at considerable length in what he clearly knew to be the last years of his life. And the pursuit of a plausibly full answer to the question of what it meant for Donald Harington to write novels has continued in the decade or so that has passed since his passing, particularly in the Harington archive housed by the University of Arkansass Special Collections and in the computer files that were approved for this research. You now hold the result of these efforts in your hands, this first collection of nonfiction writings and interviews by someone I once nicknamed (to his great pleasure, as he later told me) the court jester of the Ozarks.

Haringtons work has always appealed at least as much to the general reader (or, as Harington nominates her in When Angels Rest, Gentle Reader) as it does to the literary scholar, and his own long (and frustrating) quest for success in the literary marketplace showed how ardently he courted the former, elusive quarry. An art historian and a technically uncredentialed but superbly knowledgeable (and opinionated) student of literature himself, Harington was quite at home among other scholars, of course, but it was clear to anyone who discussed his works history with him that he would have traded all the favorable reviews and the awards he had won for the kind of sales that his friends and rivals, like John Irving and Cormac McCarthy, enjoyed. So, in preparing a volume of Haringtons nonfiction that will serve the efforts of both kinds of readers, I have tried not just to provide texts that will shed more light on his many inspirations and thicken scholarly appreciation of his favorite themes, but also to provide his beloved Gentle Reader with another pleasurable Harington reading experience, a fresh and deepened perspective on the restless mind that was tied so firmly (if, for him, frustratingly) to his equally restless but tender heart. In an interview included in this volume, Harington declares his work to be primarily intellectual, for the head, and only secondarily emotional, for the heart, but like any of his novels, this volume of his nonfiction shows how beautifully the two collaborated in all of his creative endeavors.

The various texts that comprise this miscellany invite you to enjoy still more of the imposing learning that made Haringtons novels possiblythe most quirky and inventive corpus in American letters, as a reviewer once put it. But perhaps more importantly, they invite you to see that, no matter what he was writingessays, reviews, or responses to interview questions that he couldnt hear and which were thus submitted to him in writing Harington was always the novelist, always spinning yarns, rigging up plotlines to hook, entrance, and delight the Gentle Reader whom he loved so dearly (sometimes desperately) through the medium of his written words. Harington was an incorrigible storyteller, a loving co-conspirator with anyone who would set foot into his imaginary realms, to our perpetual enrichment as readers.

The three sections of nonfiction in this Guestroom Novelist commence with the eponymous essay, which Harington first wrote as a talk to be delivered at Texas Christian University and which he then, without success (in a frustrating pattern that most writers can sympathize with), tried to sell to a variety of editors. It offers an almost perfect example of his take on the figure of the writer: decades of frustration and bitterness transmuted into a generous series of love letters to fellow accomplished, worthy, but commercially unsuccessful authors, a potential rant about the fickleness of the fiction marketplace gentled and deepened into a well-researched, systematic, wryly lively gift to curious readers and gifted but lonely writers everywhere.

The themes realized so thoughtfully and with such restless love in the title essay reappear, in various guises, throughout the essays, speeches, reviews, and interviews that follow. Over and over again, Harington emphasizes and embodies the personal nature of both the writing and the reading experience, the connections between logophilia, gifted logorrhea (such as he was blessed with), and the desire for an other, a partner for both the mind and the heart. Whether hes discussing the soul-soothing comforts of his mother-in-laws chicken-and-dumplings, or taking museum directors to task for failing to realize their glorious mission, or licensing the readers most dubious responses to a painters most dubious portraits, Harington consistently humanizes, illuminates, and enlarges his topics as a gift to the reader, an invitation to join him in the Stay More of his imagination for respite and repast that will last a lifetime (however creatively lonely that lifetime may turn out to be).