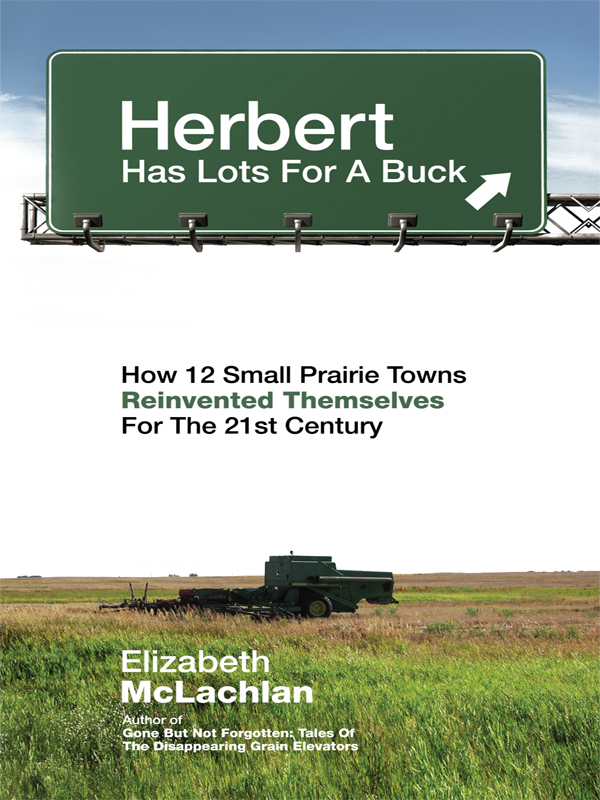

How 12 Small Prairie Towns

Reinvented Themselves

For The 21st Century

Elizabeth

McLachlan

Copyright Elizabeth McLachlan 2012

All rights reserved. The use of any part of this publication reproduced, transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, recording or otherwise, or stored in a retrieval system, without the prior consent of the publisher is an infringement of the copyright law. In the case of photocopying or other reprographic copying of the material, a licence must be obtained from Access Copyright before proceeding.

Library and Archives Canada Cataloguing in Publication

McLachlan, Elizabeth, 1957

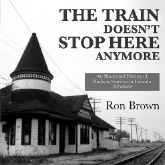

Herbert Has Lots For A Buck: How 12 Small Prairie Towns Reinvented

Themselves For The 21st Century/ Elizabeth McLachlan

Also issued in electronic format.

ISBN 978-1-927063-23-1

1. Cities and towns--Prairie Provinces--Growth--History-

21st century. 2. Prairie Provinces--Economic conditions--1991-.

I. Title.

HT384.C32P73 2012 307.1416309712 C2012-902347-7

Editor for the Board: Don Kerr

Cover and Interior Design: Greg Vickers

Author Photo: James Baron

NeWest Press acknowledges the financial support of the Alberta Multimedia Development Fund and the Edmonton Arts Council for our publishing program. We further acknowledge the financial support of the Government of Canada through the Canada Book Fund (CBF) for our publishing activities. We acknowledge the support of the Canada Council for the Arts which last year invested $24.3 million in writing and publishing throughout Canada.

201, 8540109 Street

Edmonton, Alberta | T6G 1E6

780.432.9427

www.newestpress.com

We are committed to protecting the environment and to the responsible use of natural resources. This book was printed on 100% post-consumer recycled paper.

1 2 3 4 5 13 12 | Printed and bound in Canada

Dedicated to Connie Penner

Small towns more than 90 minutes drive from a city

are usually locked in a struggle to avoid shrinking or

dying. Just to maintain the size of a small town requires

incredible ingenuity on the part of its citizens, or

incredible desperation.

Fred Stenson

Alberta Views (July/August 2004)

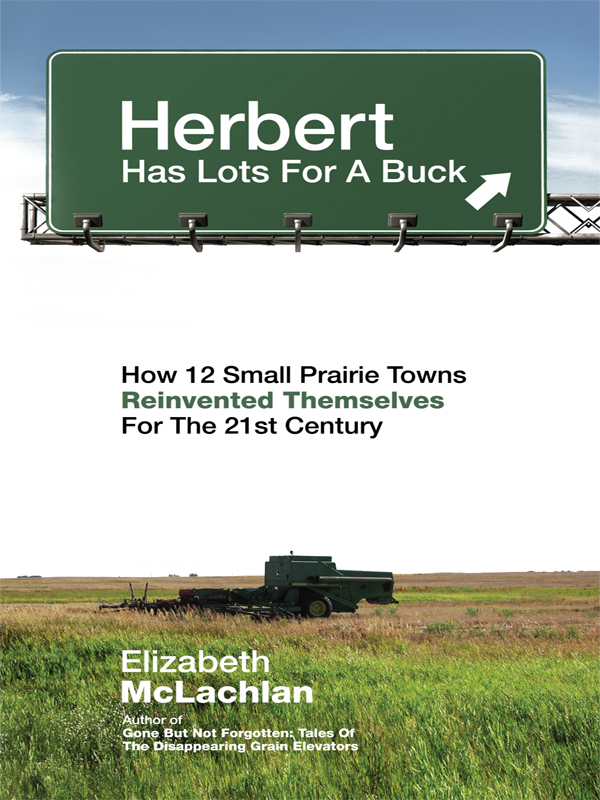

Herbert Has Lots For A Buck.

Promotional Sign

Outside Herbert, Saskatchewan

Table Of Contents

I recently drove through the tiny hamlet of Kirkcaldy, in southern Alberta. The town appeared to consist of one street that bowed off Highway 23 at one end and back onto it at the other. I thought it was deserted. There were abandoned buildings and ancient gas pumps, faded paint and broken windows. It was a bright midsummers day, yet I saw not a soul.

But wait! There came a German shepherd, bounding happily out to greet me from a flower-gilded yard that was neatly grassed, trimmed, and (thankfully) fenced. And a little farther up the street stood a signpost, proudly announcing the Goldhawks lived here. Another residence, in an arty show of nostalgia, displayed a vintage Alberta Wheat Pool sign at the entrance to its well-kept driveway. Little Kirkcaldy was breathing. Her residents were affluent enough and cared enough to take pride in their yards and homes, to appreciate art and history.

But where was the church? The store? The school? The post office?

Throughout the Canadian prairies (as throughout Canada and the world) rural depopulation is a reality. The myriad reasons spin together in concurrent cause-and-effect cycles. To begin with, mechanization allows fewer people to accomplish more work. Family farms, once prolific enough to warrant a small school every four to six miles, grew in size and diminished in number; diesel locomotives eliminated the need for rural roundhouses and rail crews; dial telephones rendered exchanges obsolete; paved roads and better cars made travellingand spending money elsewhere attractive; straightened highways bypassed towns they once bisected; city department stores (and, later, big box chains) offered merchandise at prices small-town shopkeepers couldnt compete with; branch rail lines terminated passenger service, then freight service, and finally closed completely; grain companies decommissioned hundreds of community elevators; churches closed, government services withdrew, and school districts consolidated. Rural children bused to larger centres for their education never fully returned, their emotional ties with their home communities now weakened, and ease of travel and better job prospects luring them away. In a slow erosion, which began decades ago, farm kids, telephone operators, business owners, elevator agents, railway employees, teachers, post office workers, clergyand anyone associated with failing businesses and discontinued servicesheaded for the cities, taking their families, tax dollars and civic leadership skills with them. They left landscapes strewn with abandoned buildings and thinning, aging populations. Cities growing fat with rural migrants soaked up the towns around them, encroaching on an ever-sparser countryside. In the 1940s, when the accumulation of all these changes finally tipped the scales, almost half of Canadas population was rural. Today, 80 per cent live in urban environments, and more than half the farms are large-scale, corporate, factory operations. Communities that once sustained, and were sustained by, agricultural surroundings, are dying. Add those struck down by resource depletion and the impact of climate change, and the course is set.

The economic, social, and environmental consequences of rural out-migration are well-studied and documented. The researchers I encounteredDrs. Dave Whitson and Debra Davidson (University of Alberta), Dr. JoAnn Jaffe (University of Regina), and Dr. Roger Epp (Augustana Campus, U of A)are just a few who have made significant contributions to an understanding of rural degeneration. Their work represents a growing body of academic investigation into a field of escalating concern.

This book, however, is neither academic in nature, nor is it about degeneration. Rather, it is a look at communities that should have died, but didnt. Despite losing grain elevators, post offices, schools, grocery stores, and other essential services, they are thriving.

As I researched communities in Alberta, Saskatchewan and Manitoba that found waysoften highly original onesto attract new people, retain those who stayed, and stabilize economies, three varieties emerged:

(1) Towns that had died, or were dying, and came back to life.

(2)Towns which were still viable but sensed advancing deterioration.

(3) Towns that have been long dead, but have refused to go away.

The latter category includes places like Snipe Lake, Saskatchewan; Retlaw, Alberta; and Rowley, Alberta. In Snipe Lake, a single resident continues to live in and promote the town. She calls herself the mayor and, since she uses the town fire truck to water her garden, she lays claim to the title of fire chief as well. In Retlaw, a lone family dwells in a holiday trailer during mild months. Presumably they are the ones who every year plant flowerbeds, fill tubs, pots, and pails with abundant blooms, and watch over whats left of the community: a restored, historic church; a community hall; a ball diamond with Retlaws Field of Dreams painted on its backstop, and a prettily appointed picnic shelter with the following posted message:

Next page