Paperback edition, 2022

by the University of Georgia Press

Athens, Georgia 30602

www.ugapress.org

2005 by Vincent Carretta

All rights reserved

Designed by Kathi Dailey Morgan

Set in Berthold Baskerville, Trajan, and Bickham Script

Map design by Deborah Reade

Printed and bound by Integrated Books International

The paper in this book meets the guidelines for

permanence and durability of the Committee on

Production Guidelines for Book Longevity of the

Council on Library Resources.

Most University of Georgia Press titles are

available from popular e-book vendors.

The Library of Congress has cataloged the

hardcover edition of this book as follows:

Carretta, Vincent.

Equiano, the African : biography of a self-made man / Vincent Carretta.

xxiv, 436 p. : ill., maps ; 25 cm.

Includes bibliographical references (p. 395417) and index.

ISBN-13: 9780820325712 (hardcover : alk. paper)

ISBN-10: 0820325716 (hardcover : alk. paper)

1. Equiano, Olaudah, 17451797. 2. SlavesGreat BritainBiography.

3. SlavesUnited StatesBiography. I. Title

HT869.E6 C37 2005

306.362092dc22 2005011898

Paperback ISBN-13: 978-0-8203-6298-4

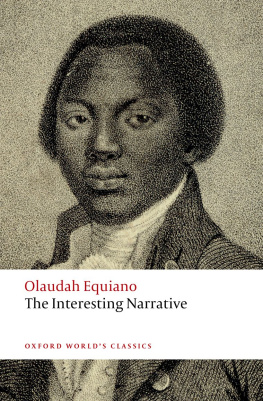

Frontispiece: Detail of the frontispiece from the first edition of volume 1 of Olaudah Equianos Interesting Narrative (London, 1789) (The John Carter Brown Library as Brown University).

PUBLICATION OF THIS BOOK WAS MADE POSSIBLE,

IN PART, BY A GENEROUS GIFT FROM

Anna, Adam, Lynne, and Steve Wrigley

Illustrations

FIGURES

MAPS

Preface

No one has a greater claim to being called a self-made man than the writer now best known as Olaudah Equiano. According to his autobiography, The Interesting Narrative of the Life of Olaudah Equiano, or Gustavus Vassa, the African. Written by Himself (London, 1789), Equiano was born in 1745 in what is now southeastern Nigeria. There, he says, he was enslaved at the age of eleven and sold to English slave traders, who took him on the Middle Passage to the West Indies. Within a few days, he tells us, he was taken to Virginia and sold to a local planter. After about a month in Virginia he was purchased by Michael Henry Pascal, an officer in the British Royal Navy who renamed him Gustavus Vassa and brought him to London. With Pascal, Equiano saw military action on both sides of the Atlantic Ocean during the Seven Years War. In 1762, at the end of the conflict, Pascal shocked Equiano by refusing to free him, selling him instead to the West Indies. Escaping the horrors of slavery in the sugar islands, Equiano managed to save enough money to buy his own freedom in 1766. In Central America he helped purchase and supervised slaves on a plantation. Equiano set off on voyages of commerce and adventure to North America, the Mediterranean, the West Indies, and the North Pole. Equiano was now a man of the Atlantic. A close encounter with death during his Arctic voyage forced him to recognize that he might be doomed to eternal damnation. He resolved his spiritual crisis by embracing Methodism in 1774. Later he became an outspoken opponent of the slave trade, first in his letters to newspapers and then in his autobiography. In 1792 he married an Englishwoman, with whom he had two daughters. Thanks largely to profits from his publications, when Equiano died on 31 March 1797 he was probably the wealthiest and certainly the most famous person of African descent in the Atlantic world.

Over the past thirty-five years historians, literary critics, and the general public have come to recognize the author of The Interesting Narrative as one of the most accomplished English-speaking writers of his age and unquestionably the most accomplished author of African descent. Several modern editions of his autobiography are now available. The literary status of The Interesting Narrative has been acknowledged by its inclusion in the Penguin Classics series. It is universally accepted as the fundamental text in the genre of the slave narrative. Excerpts from the book appear in every anthology and on any Web site covering American, African American, British, and Caribbean history and literature of the eighteenth century. The most frequently excerpted sections are the early chapters on his life in Africa and his experience on the Middle Passage crossing the Atlantic to America. Indeed, it is difficult to think of any historical account of the Middle Passage that does not quote his eyewitness description of its horrors as primary evidence. Interest in Equiano has not been restricted to academia. He has been the subject of television shows, films, comic books, and books written for children. The story of Equianos life is part of African, African American, Anglo-American, African British, and African Caribbean popular culture. Equiano is also the subject of a biography published in 1998 by James Walvin, an eminent historian of slavery and the slave trade.

These last thirty-five years have witnessed a renaissance of interest in Equianos autobiography and its author. During Equianos own lifetime The Interesting Narrative went through an impressive nine editions. Most books published during the eighteenth century never saw a second edition. A few more editions of his book appeared, in altered and often abridged form, during the twenty years after his death in 1797. Thereafter, he was briefly cited and sometimes quoted by British and American opponents of slavery throughout the first half of the nineteenth century. He was still well enough known publicly that he was identified in 1857 as Gustavus Vassa the African on the newly discovered gravestone of his only child who survived to adulthood. But after 1857 Equiano and his Interesting Narrative seem to have been forgotten on both sides of the Atlantic for more than a century. The declining interest in the author and his book is probably explained by the shift in emphasis from the abolition of the British-dominated transatlantic slave trade to the abolition of slavery, particularly in the United States, following the outlawing of the transatlantic trade in 1807.

The twentieth-century recovery of the man and his work began with the publication in 1969 by Paul Edwards of a facsimile edition of The Interesting Narrative. I have been teaching and researching Equiano since the early 1990s. I first saw his autobiography in a bookstore near the University of Maryland when I came across a copy of Henry Louis Gates Jr.s then recently published anthology entitled The Classic Slave Narratives. It includes an 1814 edition of The Interesting Narrative. Although I had heard of Equiano before then, I had never seen a copy of his work, and from what I had read about it I assumed that it was a text more appropriate for American literature courses than for the British courses I was teaching at the time. Placing Equiano in the tradition of American autobiographical writing exemplified by Benjamin Franklin went unchallenged. They were both seen as self-made men who raised themselves by their own exertions from obscurity and poverty. No one thought to point out that since the publication in London of Equianos autobiography preceded by decades that of Franklins in the United States, rather than considering Equiano an African American Franklin we would more accurately call Franklin an Anglo-American Equiano.

Attempts to pin Equiano down to either an American or a British identity are doomed to failure. Once he was free, Equiano judged parts of North America reasonably nice places to visit, but he never revealed any interest in voluntarily living there. By Equianos account, the amount of time he spent in North America during his life could be measured in months, not years. Whether he spent a few months, as he claims, or several years, as other evidence suggests, living in mainland North America, he spent far more time at sea. He spent at least ten years on the Atlantic Ocean and Mediterranean Sea during periods of war and peace between 1754 and 1785. The places he considered for a permanent home were Britain, Turkey, and Africa. Ultimately, he chose Britain, in part because Africa was denied him, despite his several attempts to get there. Truly a citizen of the world (337), as he once called himself, Equiano was the epitome of what the historian Ira Berlin has called an Atlantic creole:

Next page