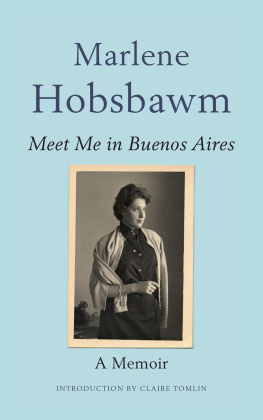

In memory of Douglas Noel Graham-Yooll and of Ines Louise Tovar and with thanks to my sister, Joanne Graham-Yooll

ed. Katherine Bucknell (Methuen, London 1996)

T HIS IS A STORY I wanted to tell you. It is my fathers story, mostly; it is written as he told it to me, in some ways. This is how his times were and the way I think they should be told. By this means he will survive me. Thus together we can make up for his early death.

My fathers is the story of Argentina, of the end of Empire; an empire built by small countries to make a strong nation and by men who knew that hard work left no time to make money but only made rich men richer.

All the characters in these pages are real, distorted by memory, influenced by imagined recollections. All the situations are true, yet none of them need to be believed. This might cause some confusion. For what we understand is not true we call fiction, and what we do not believe we call fantasy. Such rules are clear. To alter them could give rise to mistaken impressions. This record has to be so.

This is a novel which claims to be the truth, sometimes.

The starting time is in a golden age of English influence in Argentina. It is English. It is not Scottish or Welsh, or anything else, because English is what people in Argentina called it. The ingleses were superior. That age is in part memory alone. Hence the events are recreated with a dash of whim by which many people recalled that they were part of events. Many thought that they were actors with a role to play.

My father was one of those many. The English, Scots and Welsh, and the US citizens, and the Canadians and Australians too, of that period at the start of the twentieth century in South America had much in their favour. It was enough for a man, and especially for a woman, to speak English to feel better than the others. England was at the centre of the world. That time of rich memory and impoverished reality also had the possibility of adventure in places remote from conventional society.

People dreamed of a chance of success without too much work, of the titillation of moderate danger, and yet they seemed fully aware of an approaching apocalypse leading to a future crash. For Anglo-Argentina, an expatriate state in which people were constantly escaping from the surrounding reality, and for the literary genre named Southamericana, that era, of commercial success, personal escapades and English-speaking pre-eminence, began in 1918. The period was intense and short.

That time began at the end of the First World War. On 2 October 1918, The Times printed a report from its Buenos Aires correspondent that showed just how European Argentina wanted to feel:

Argentine joy at Allied victory. Buenos Aires, July 25: When brought into contact with the everyday life of Buenos Aires, it is difficult to believe that one is breathing a neutral atmosphere. Allied flags are everywhere; practically the entire Press rejoices with open enthusiasm at the news of Allied victory, and the Fourteenth of July was marked by a gigantic procession, which passed along profusely beflagged streets When the news first arrived here of the dramatic turn of fortune on the Marne and the rolling back of the Hun forces, I was walking down the Calle Florida, the principal street of Buenos Aires. Newspaper boys were shouting the latest developments with enthusiasm

European immigration and farming exports had made Buenos Aires one of the great cities of the world in under three decades. It was an attractive destination for expatriation. Think of a Europe blacked-out by war, sickness and poverty, trying to put behind it the enormous grief of long and bloody battles. Then imagine a Buenos Aires of bright lights twinkling, with the magic of wealth and new opportunities, without grief.

As recently as the end of the nineteenth century Buenos Aires had been a small town. The guide books had still been able to inventory facilities available in the urban centre that was to become a capital.

George Newness 1895 book, From London Bridge to Charing Cross Via Yokohama and Chicago, described the city as a large village. He listed four Protestant and twenty-five Catholic churches, eighty-three streets, twenty markets, fifty-five clubs, fifteen hotels, 322 schools and a fire brigade of seven companies. Helpfully, Newnes wrote:

In all parts of the city, and more especially in the vicinity of the Boca, there are numerous conventillos or common lodging houses in which human beings are crowded together in a manner unknown in the worst slums of London. Some of these dreadful rookeries contain as many as 150 to 200 apartments The air was deafened by the hiss and creak and rattle of machinery, trains, and lumbering vehicles; the hooting of tram horns, the shrill whistle of the police, the hum of myriads of insects, the incessant lurking of villainous dogs, and above all the peculiar, metallic, ear-splitting chirp of the tree frogs The appearance of the city is monotonous and dismal, the majority of the streets being only forty feet wide, with high houses, and each bloc, or manzana, covering an area of about four acres.

But the gleam of something better was there. Very cosmopolitan are the crowds on the streets of pleasure-loving Buenos Ayres. Most people are dressed in European fashion, but large numbers of Basques and Italians wear their national costumes: moreover, the poorer classes of Argentine women still wear their picturesque mantilla, wrote Newnes.

By the end of the First World War, Buenos Aires had nothing of the small town and was growing rapidly, in a haphazard way. J.A. Hammerton, author of The Argentine Through English Eyes, wrote in the Argentina chapter of Peoples of All Nations, a twelve-volume cyclopedia published in 1923:

There is no romantic element in the character of the Argentine today. The vision of opportunities to make money in large quantities, and in a few years without much labour, took hold of him as soon as the development of the Republic by foreign capital began to bear fruit. He thinks about money all his time, he talks about it most of the time, he spends it lavishly, both in Buenos Aires and in Paris, and he is always planning how to get more

This aspect of Argentina, Argentines, Argentineans, whatever, would never change. This was the country that the Prince of Wales, later Edward VIII, and then the Duke of Windsor, found on arrival in 1925. For the British and North Americans, corporations and individuals, in Argentina the decade was developing into one of comfort and success, of money, lots. Business had little difficulty in its operations.

President Alvear liked the English and tried to accommodate their wishes. The threat from an organized trades union movement had been eliminated after a decade of growth in labour strength. A strike in 1920 at the British-owned tanine producers, The Forestal Land, Timber and Railways Company in Santa Fe, had been crushed by the army. The defeat of a strike at the port of Buenos Aires, in May and June 1921, put an end to years of union progress. And the powerful railway unions had also been demolished. In Patagonia, a strike organised by expatriate European anarchists at British-owned sheep farms had been ended by the army, with the execution of the ring-leaders who fell riddled with bullets into the graves they had dug.

English and Scottish emigrants, travelling on their own, were favoured by a post-war fall in European immigration to Argentina. This made jobs easy to find for the loner with something of an education. Argentinas interests in foreign commerce made employment with export traders attractive and easily available.