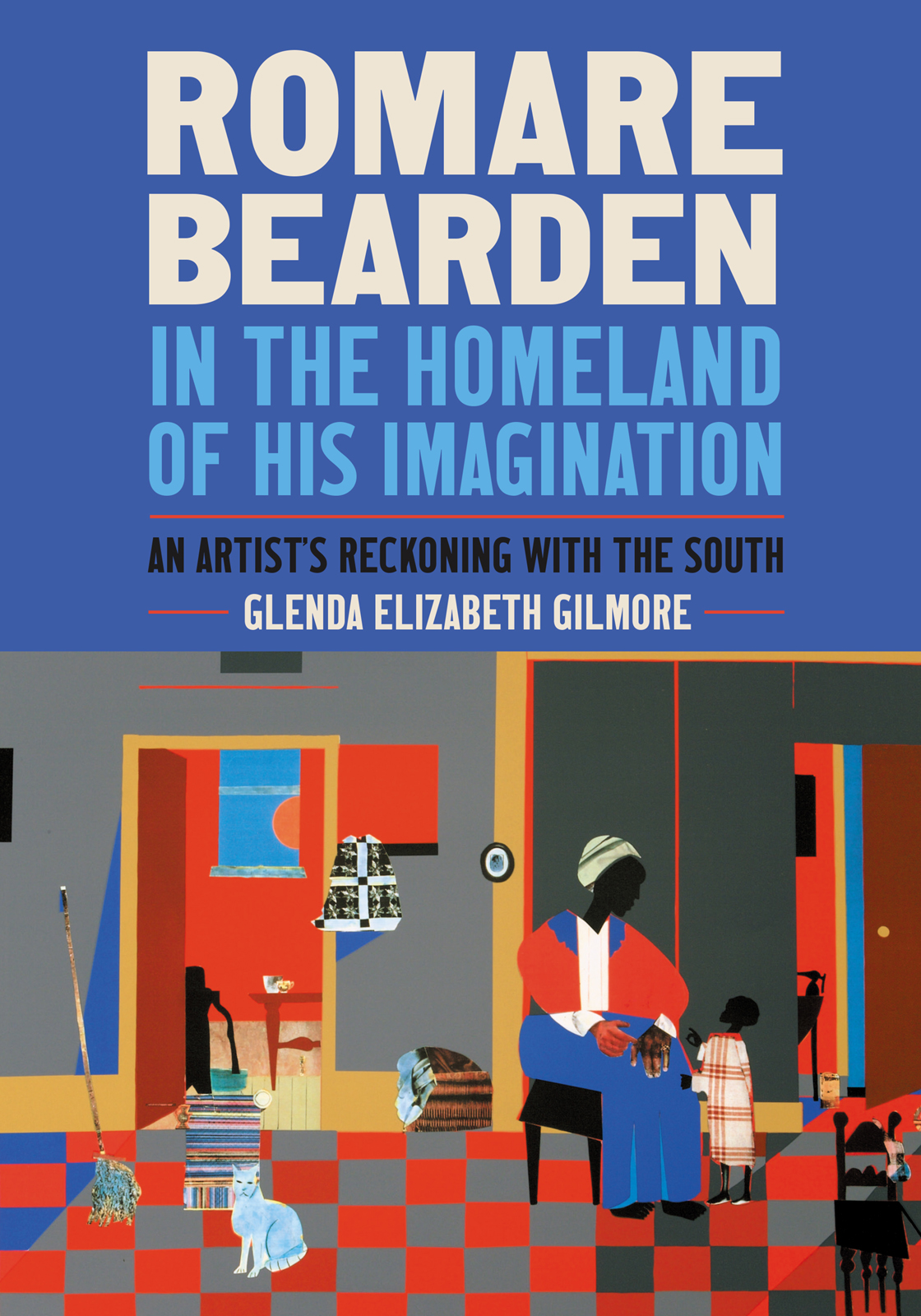

ROMARE BEARDEN IN THE HOMELAND OF HIS IMAGINATION

AN ARTISTS RECKONING WITH THE SOUTH

GLENDA ELIZABETH GILMORE

A FERRIS AND FERRIS BOOK

THE UNIVERSITY OF NORTH CAROLINA PRESS

CHAPEL HILL

This book was published under the Marcie Cohen Ferris and William R. Ferris Imprint of the University of North Carolina Press.

2022 The University of North Carolina Press

All rights reserved

Manufactured in the United States of America

Designed and set by Lindsay Starr in Monotype Dante by Monotype

The University of North Carolina Press has been a member of the Green Press Initiative since 2003.

Cover illustration: Romare Bearden, Profile/Part I: The Twenties, Mecklenburg County, Early Carolina Morning, 1978. Serigraph, 21 29 in. Image courtesy Romare Bearden Foundation and the Wildenstein Plattner Institute, Inc. ArtRomare Bearden Foundation/Licensed by VAGA at Artist Rights Society (ARS), NY.

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

Names: Gilmore, Glenda Elizabeth, author.

Title: Romare Bearden in the homeland of his imagination : an artists reckoning with the South / Glenda Elizabeth Gilmore.

Description: Chapel Hill : University of North Carolina Press, [2022] | A Ferris and Ferris bookTitle page. | Includes bibliographical references.

Identifiers: LCCN 2021052604 | ISBN 9781469667867 (cloth ; alk. paper) | ISBN 9781469667874 (ebook)

Subjects: LCSH: Bearden, Romare, 19111988. | Bearden, Romare, 19111988Family. | African American artistsBiography. | African American artistsSouthern States. | Middle class African Americans.

Classification: LCC N6537.B4 G55 2022 | DDC 709.2dc23/eng/20211217

LC record available at https://lccn.loc.gov/2021052604

A version of .

To my family, Ben, Miles, Derry, and Mia-lia, who gave me the homeland that I once could not have imagined

CONTENTS

ILLUSTRATIONS

ROMARE BEARDEN IN THE HOMELAND OF HIS IMAGINATION

INTRODUCTION

You know, in Eliots poem, The Four Quartets, he talks about time, and youre going back to where you started from, but maybe youre bringing another insight, another experience to it. And things that may be nonessential have been stripped away, and you can see that the things that still stick in your mind must be of some importance to you. Like the people I remember, the pepper jelly lady, a little girl [who] kind of played with me, Liza. All of these things that now came back to me. ROMARE BEARDEN, 1980

R omare Bearden, among the most renowned artists of the twentieth century, could conjure only episodic glimpses of Charlotte, North Carolina, where he was born on September 2, 1911. As a historian, my first task was to recover the factual history of the Bearden and his forebears. Some of my discoveries contradict Beardens own and others accounts. Other recovered sources, reported here for the first time, add information that Bearden never knew; in fact, they include some things he could never have known. The contradictions between the historical record and how Bearden recounted his life and family background create a fruitful tension between how historical facts and ones own lived experiences coincide and collide. It is my intention to credit both. Beardens accounts, based on what he believed to be true, carry historical weight in and of themselves.

He could not tell precisely what he remembered or what generalized African American culture, particularly Black southern culture, evoked for him. As he created paintings and collages, he often did not know what was real, what was partially real, and what was a dream. This creative conundrum drove his artistic expression and sparked his imagination. The contrasts of history and memory also testify to the violence that slavery and Jim Crow wrought on African American memory and self-representation. A century and a half of historical neglect, family secrets, silences, and a racist archive that hides the Black past stole a factual family story from Bearden, even as he often tried to capture it visually.

Bearden represented the fourth generation of the African American Kennedy-Bearden family, who lived together in a family compound in the midst of the growing city. He began life bathed in love and certain of his place in life. White supremacy drove his parents to Harlem in 1915, and he grew up there and in Pittsburgh. A formally trained artist, he devoted himself to his art from the 1930s until his death on March 12, 1988, even as he worked full-time as a social worker for thirty years.

Beardens artistic trajectory reflects the history of twentieth-century art. He moved from social realism in the 1930s, to abstract expressionism in the 1940s. When he turned to creating collage paintings in the late 1950s, he became a nationally acclaimed artist and produced hundreds of works. Through his entire career, he saw himself as a cubist, even as his work changed radically over time.

The traditional narrative of Beardens life is an American story that posits his familys progress as linear, steadily improving, as racial discrimination inexorably faded from the Emancipation Proclamation to Martin Luther Kings I Have a Dream speech. But Beardens life and those of three generations of his southern Black family before him belie the myth of Black people unceasingly rising as they climbed. Instead, the political economy of racism constantly remade itself to thwart the Kennedys and Beardens hopes. Their family story is a compelling saga of middle-class Black achievement in the face of relentless waves of white supremacy.

Beardens great-grandparents entered Reconstruction with considerable advantages: literacy, a federal job, and small businesses. They owned outright a large Victorian home with a wraparound front porch, two rental houses, and a store. Each subsequent generation followed the playbook of the American dream: they became educated, worked hard, and were civic activists. But time and time again, the inexorable growth of direct white oppression and systemic racism always threatened their place. It diminished the values of their homes and businesses, forced college graduates into menial jobs, and caused them to flee the South for their safety.

Romare Bearden in the Homeland of His Imagination explores his own and his familys lives through his art. It follows many essays on Beardens life, but only two other book-length biographies: Mary Schmidt Campbells comprehensive treatment, An American Odyssey: The Life and Work of Romare Bearden, and Myron Schwartzmans oral history, Romare Bearden: His Life and Art.

Existing biographical essays and monographs, with the exception of Campbells American Odyssey, are based primarily on oral interviews that Bearden gave throughout his life. Schwartzman adds limited archival work to his substantial oral interviews with Bearden. Yet in the thirty years since the publication of Schwartzmans Romare Bearden: His Life and Art, as interest in Beardens life and family history has grown, new historical tools with which we can uncover the African American past have emerged.

Bearden understood the tension between history and memory. He told an interviewer, Time is a pattern. You can come back to where you started from with added experience and you hope for more understanding. His memories slipped the bonds of reality and entered the realm of the mythical. Moreover, contributing to the tension between history and memory is that Bearden only rarely corrected others representations of his past. He did not object to reading that he was born and grew up in a southern farm cabin, when, in fact, he was born in a middle-class, urban home and left the South at the age of four. His concern was always with the universal human experience, not with his individual life as exceptional. If others identified with his past and found meaning there, he would not interfere.