Contents

Guide

Page List

For John R. Grant, fellow traveler

CONTENTS

CONTENTS

LARGER

THAN

THAN

LIFE

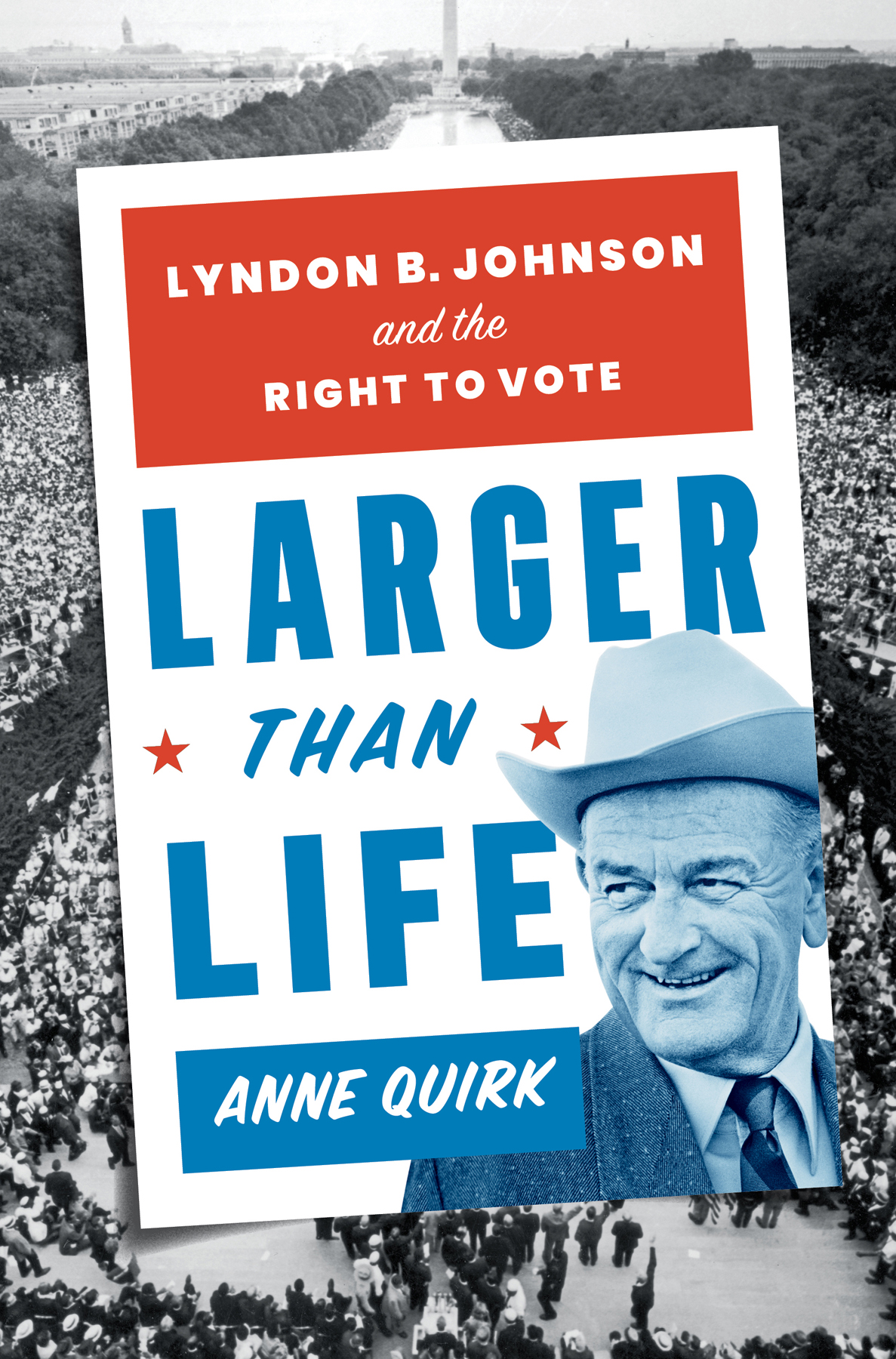

PRESIDENT LYNDON JOHNSON, MARCH 15, 1965

O n Sunday, March 7, 1965, hundreds of Americans were beaten, bloodied, and gassed by state troopers and local police officers when they tried to march across the Edmund Pettus Bridge in Selma, Alabama.

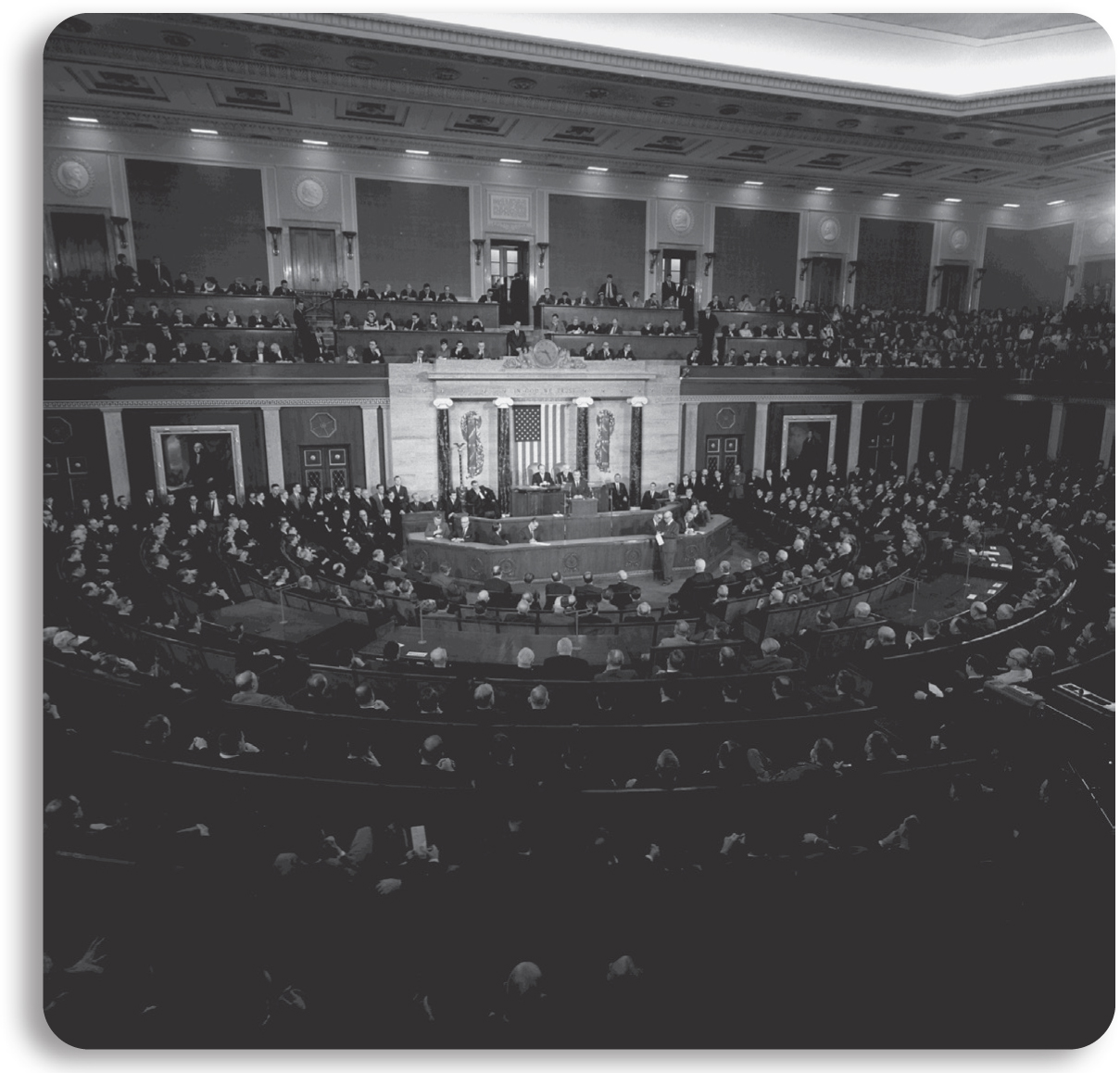

Eight days later, on March 15, President Lyndon Baines Johnson, who didnt like giving speeches and wasnt very good at it, delivered the best speech of his life. He stood at a podium in the well of the House Chamber, the great hall in the United States Capitol Building where the House of Representatives meets.

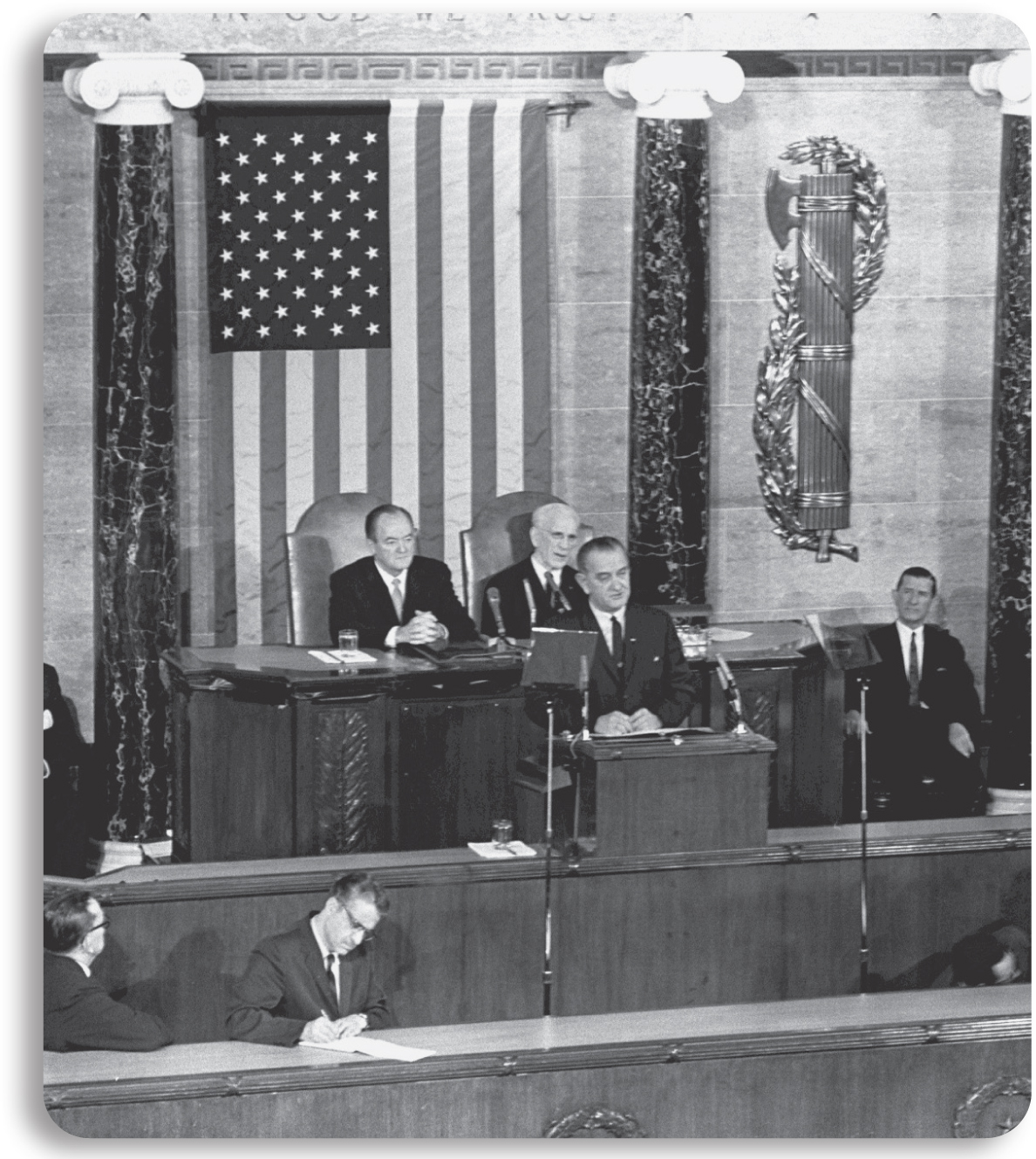

Just behind Johnson, in a matched pair of oversized chairs, sat Hubert Humphrey, the vice president of the United Stateswhose official duties include presiding over the Senateand John McCormack, the Massachusetts congressman who served as Speaker of the House. The vice president was straight-backed and alert. The seventy-three-year-old Speaker was equally engaged, but frail, sometimes looking as though he might slide off his imposing seat.

President Lyndon B. Johnson addresses a joint session of Congress on the right to vote, March 15, 1965.

Almost every member of the House of Representatives was in the chamber that night. So were nearly every senator, all nine Supreme Court justices, and each member of the presidents cabinet. The longtime head of the Federal Bureau of Investigation, J. Edgar Hoover, was there. Mrs. Johnson was side by side with her oldest daughter, Lynda. There were no empty seats in the hall. There wasnt much more standing room in its aisles, either. Tens of millions of Americans watched the speech on their televisions. Those with the most up-to-date equipment were even able to view it in color.

But all five representatives from Mississippi and both of its senatorsthe states entire congressional delegationboycotted the event. They knew what was coming, and they wanted no part of it.

I speak tonight, began the president, for the dignity of man and the destiny of democracy.

His voice was steady, but his eyelids drooped, as though he hadnt slept well for days, or maybe weeks. Perhaps even years.

More than a century had passed since slavery was abolished, he reminded his audience. Nearly that long had elapsed since African American citizens had been assured the right to vote. Yet, throughout a vast region of the country, Black Americans were being systemically denied their civil rightstheir legal privileges as citizensby state and local laws that were cruel, hateful, and wrong.

No one in the chamber that nightor in homes across the countrycould possibly have forgotten the atrocities that had just occurred in Selma, Alabama, but Johnson still recounted the attack on long-suffering men and women [who] peacefully protested the denial of their rights as Americans. Many were brutally assaulted. One good man, a man of God, was killed.

Our consciences, the president insisted, and our Constitution demand action. Right here, right now.

He promised that in two days, he would send a detailed proposala billto Congress for a national voting rights law that would secure the most basic right of a democratic nation: the right to vote.

Vice President Hubert Humphrey (left), who also serves as president of the Senate, and Speaker of the House John McCormack (right) sit behind the president.

Our nation has been blighted for too long by bigotry and injustice, he insisted. We cant wait any longer to solve these problems. They will not be easy to overcome, he admitted, but they must be overcome.

And we shall overcome.

A jolt passed through the great hall and the nation.

Lyndon Johnson was reciting the pledge of civil rights activists. This white man with deep roots in the Souththis lifelong politician with a history of accommodating segregationists and compromising with white supremacistswas adding his voice to the chorus of men and women who had taken to the streets, marching, singing, sometimes even risking their lives, for racial justice.

The president of the United States was declaring that the nation would finally fulfill its promise that all Americans were created equal, not just some Americans.

And we shall overcome.

A few congressmen sat on their hands, kept their faces blank, fixed their eyes on the middle distance, but most of the chamber erupted in cheers. Up in the gallery, where the visitors sat, tears flowed.

Martin Luther King Jr., the most prominent civil rights leader of his time, watched the speech from a friends home in Alabama. The thirty-six-year-old was world famous, the most recent recipient of the Nobel Peace Prize. He was polished, thoughtful, and dignified. He was not a crier.

But that night, Martin Luther King Jr. cried.

The president wasnt ready to sit downnot yet. He spoke about a job he had in 1928, at a school in a town in south Texas. Back then, he was twenty years old, taking a year off from Southwest Texas State Teachers College because he couldnt afford its twenty-dollar-per-semester tuition.

Like most gifted storytellersand canny politiciansLBJ was more than willing to stray from the facts when it served his purpose. The tale he told that night wasnt accurate in every detail, but it was true in the deepest way: it came from his heart.

My first job after college was as a teacher in Cotulla, Texas, in a small Mexican-American school, he recalled, even though he was actually still in college at the time. Johnsons lack of a diploma was one of the reasons he got the job in the first place. An experienced teacher would have cost more and might also have refused to work with non-Anglo students.

Few of them could speak English, he explained about the pupils at the Welhausen School, and I couldnt speak much Spanish. My students were poor and they often came to class without breakfast, hungry. They knew, even in their youth, the pain of prejudice. They never seemed to know why people disliked them. But they knew it was so, because I saw it in their eyes, he said. Somehow you never forget what poverty and hatred can do when you see its scars on the hopeful face of a young child.

I never thought then, in 1928, that I would be standing here in 1965, he said, taking another short detour from the facts. Even as a twenty-year-old, perhaps even as a ten-year-old, Lyndon Johnson had set his sights on getting to the White House eventually.

CONTENTS

CONTENTS THAN

THAN