ALSO BY JULIAN E. ZELIZER

CHAPTER ONE

THE CHALLENGES OF A LIBERAL PRESIDENCY

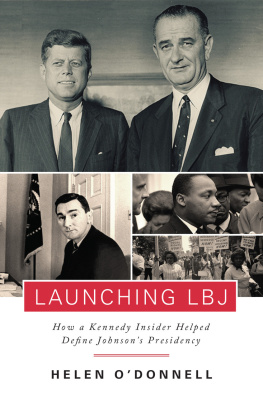

L yndon Johnson hated being vice president. He was at heart a legislator who had been relegated to the sidelines of legislation. For almost three years he had watched John F. Kennedy fumble most of the big domestic issues of the day, either because the president was unwilling to take on the toughest challenges of the moment, or because he was too afraid of the political fallout, or because he knew he lacked the ability to win the legislative battles he faced on Capitol Hill. At the time of Kennedys death, most of his major domestic initiativesincluding civil rights, a tax cut, federal assistance for education, and hospital insurance for the elderlywere stalled in Congress or had not yet been introduced there. Kennedy and his advisers had made a conscious decision to keep Lyndon Johnson out of their inner circle, despite his extensive experience on Capitol Hill, for fear that his well-known thirst for power would cause problems for the president.

At 4:00 a.m. on November 23, 1963, the day after Kennedys assassination gave him the presidency, Johnson reclined on his bed, his top advisers arrayed around him for an impromptu meeting. He mapped out a grand vision for his team. The new president told Jack Valenti, Bill Moyers, and Cliff Carter, with relish and resolve, according to Valenti, Im going to get Kennedys tax cut out of the Senate Finance Committee, and were going to get this economy humming again. Then Im going to pass Kennedys civil rights bill, which has been hung up too long in the Congress. And Im going to pass it without changing a single comma or a word. After that well pass legislation that allows everyone anywhere in this country to vote, with all the barriers down. And thats not all. Were going to get a law that says every boy and girl in this country, no matter how poor, or the color of their skin, or the region they come from, is going to be able to get all the education they can take by loan, scholarship, or grant, right from the federal government. After pausing to catch his breath, almost as if exhausted by his own ambitions, the president concluded, And I aim to pass Harry Trumans medical insurance bill that got nowhere before.

Jack Valentis recollection of that moment perfectly portrays the Lyndon Johnson who had suddenly become the nations leader. He was a creature of Congress, a legislator by character and long experience, who was determined to push through a transformative body of laws that would constitute nothing less than a second New Deal.

Though many liberals had long doubted that Johnson was anything but a southern racist conservative who sometimes pretended to be one of them, he was, when he became president of the United States, truly determined to expand the role of the federal government in domestic life far beyond what his hero Franklin Roosevelt had accomplished. Johnson had started in politics as a New Deal liberal, and over the years he had grown ever more determined to deal with issues FDR had ignored and on which Johnson himself had been ambivalent at best during his own political career, most notably civil rights and health care. He wanted to use the presidency to build legislative majorities behind the ideas that liberals had been discussing and deliberatingbut not enacting into lawfor more than a decade.

Lyndon Johnsons vision of a presidency that would spearhead major liberal legislation faced enormous obstacles, however. Historians have often failed to understand how the Great SocietyPresident Johnsons agenda of big domestic programswas enacted, because they have accepted two myths about the nature of the political challenges the Great Society had to face.

The first myth presents the 1960s as the apex of modern American liberalism, the culmination of those forces that arose in the Progressive Era at the turn of the twentieth century when the federal government came to be seen as a positive good, when social movements leaned toward the left, and when conservatives were marginal and irrelevant.

A recent generation of historians has shattered this portrait of the liberal era in politics. They have rediscovered the enormous influence of conservative activists, philanthropists, organizations, and politicians in the decades that directly followed the New Deal. Shifting attention away from the White House and toward the U.S. Congress is one of the most effective ways to gain a very different perspective on the dynamics of American politics before the age of Reagan. Though many of the nations presidents had embraced liberal ideas, Congress was a powerful institution dominated by a conservative coalition of southern Democrats and Republicans who rejected liberalism. During the 1930s, as the political scientist Ira Katznelson has shown, FDR was already forced to compromise his New Deal to appease southern Democrats and Republicans by agreeing to federal legislation that protected the racial order of Dixie and made it difficult for organized labor to gain a foothold in that low-wage nonunion region.

After the 1930s, Congress was a graveyard of liberal legislation. At the time of President Kennedys death, the record for liberal reform was meager. The spirit of the New Deal seemed a distant memory. It had been two and a half decades since any significant social legislation had been passed. President Truman lacked the skills of his predecessor, and he spent much of his political capital advancing the nations involvement in the cold war. Congressional conservatives killed most of his marquee domestic proposals, including national health care, and even turned back one of the hallmark achievements of the New Deal, the Wagner Act, which had guaranteed the right of workers to organize into unions and created the National Labor Relations Board to supervise union elections, by passing the 1947 Taft-Hartley Act, which allowed states to enact right to work laws that made it more difficult for unions to organize workers. The Republican president Dwight Eisenhower, though he accepted the permanence of the New Deal, had limited domestic policy aims and spent much of his second term pushing back against liberal Democrats in Congress who were demanding that the government do more, and spend more, to tackle social problems. President Kennedy, a hard-nosed pragmatist who continually rebuffed liberals who he believed had unrealistic expectations of what could be accomplished through legislation, saw his fears confirmed when he was soundly throttled by the conservatives in Congress on a number of proposals. As Kennedy pointed out in an interview in 1962, I think the Congress looks more powerful sitting here than it did when I was there in the Congress.