ALSO BY DAVID MARANISS

First in His Class: A Biography of Bill Clinton

Tell Newt to Shut Up! (with Michael Weisskopf)

SIMON & SCHUSTER

Rockefeller Center

1230 Avenue of the Americas

New York, NY 10020

www.SimonandSchuster.com

Visit us on the World Wide Web: http://www.SimonSays.com

Copyright 1998 by David Maraniss

All rights reserved, including the right of reproduction in whole or in part in any form.

S IMON & S CHUSTER and colophon are registered trademarks of Simon & Schuster Inc.

Designed by Edith Fowler

ISBN 0-684-86583-1

eISBN: 978-0-684-86583-6

PART ONE

Waiting for Clinton

ONE

I SUPPOSE it had to come to this, I thought to myself as I sat in the darkness of the NBC studio nook in New York, waiting for the familiar image of Bill Clinton to appear on the monitor. In a few minutes, Clinton would deliver a televised address to the nation concerning his extramarital sex life, a subject that no president before him had been compelled to discuss in public. It was obvious that he dreaded giving this speech, but circumstances had forced him into it; he thought his career was on the line. As his biographer, I would be asked to try to explain him, both what his words meant and why he had reached such an unfortunate moment. I had spent six years studying Clinton, but emotionally I had now moved beyond him, onto the subject of my next biography, Vince Lombardi, the old Green Bay Packers coach, a resolute symbol of the past who seemed to be the antithesis of the prodigal young president. It was nonetheless still impossible to escape Clinton professionally; he kept doing things that yanked me as a reporter back into his world.

Another thought troubled me more. I liked to believe, perhaps naively, that the freest of all things was the human will, that we can learn and respond and change. Clintons life kept threatening that assumption. He was a protean character who constantly adapted to his environment, an intelligent man with an extraordinary memory for names and faces and events and an uncommon ability to assemble facts and synthesize arguments, yet at a deeper level he seemed incapable of learning and changing. He was like General George Armstrong Custer as described by biographer Evan Connell before the Battle of Little Bighorn, his fate determined by the immutability of his character, reacting predictably to the same stimuli again and again and again.

As I waited for Clinton to deliver his August 17 apologia for having some form of sex with the young intern, Monica Lewinsky, and lying about it, my mind drifted back to the first time I had interviewed him, more than six years earlier. The date was January 20, 1992, exactly one year before his first inauguration. We were gliding through the night in the backseat of a dark blue Buick taking him from Annapolis to the Washington suburbs. Questions about his sexual behavior had already become part of the early campaign discussion that year. At a debate of the Democratic presidential candidates in New Hampshire, he had been asked about the sexual innuendo that surrounded him, and he had responded that he did not think there was reason for anyone to expect embarrassing stories to emerge about his sex life. After covering Gary Hart in 1984 and writing about Harts self-implosion on issues of sex in 1987, I found Clintons answer curiously imprecise. Reconfiguring the question in the context of Harts political demise, I asked Clinton about it again during my interview with him for a profile I was writing for The Washington Post: Do you understand how many millions of people you might let down if you won the nomination and then were confronted with stories like those that hounded Hart out of the race?

Clinton did not look at me when he answered, nor did he respond directly to the question. He began to talk, then took a phone call from Jesse Jackson on his cell phone, all uh-huhs and southern whispers, then got off the phone and sarcastically disparaged Jackson as a pest, then returned to what amounted to a long diversion, saying that he didnt want to get into Gary Hart, but that Harts situation was an entirely different matter from his own. The fact that he would not engage the larger question of consequences left me feeling uneasy about him, though in other ways I found his lifes story colorful and intriguing. A few days later, the Gennifer Flowers story broke.

And now here we were, all these years later, with Clinton a second-term president fighting to save his job in the face of a sex scandal (and coincidentally turning to that same Reverend Jack son for family counseling)and with that first question I asked him in the back of the dark sedan still hovering out there, unanswered. It is the reason why I never thought of his sexual behavior as exclusively a privacy issue, nor merely as a matter of sex. It seemed to me a matter of narcissism, arrogance, stupidity, and cynicism. If he knew from the beginning that his enemies were out to get him, as he and his wife, Hillary Rodham Clinton, have so often claimed, then he also knew where he was most vulnerable to attack. That was the reality, and it transcended whatever he or anyone else thought about the relevance of a public officials private life or the obsessively invasive nature of his prosecutorial adversary. I always thought that he and his supporters had strong arguments against the special prosecutor and that in the end the process might be remembered as much as the substance of Clintons wrongdoing. I also oppose the death penalty, and believe the issue of capital punishment is far larger than any individual case, but that does not excuse the murderer or make it less important to remove him from society or to understand why he murders and to deplore the consequences of his acteven when police use questionable means to catch him.

Clinton is a dissembler, far from a murderer, despite the fantastical tales of his wildest enemies, so the analogy is not precise, but the point is much the same. The writer Francine du Plessix Gray, biographer of the Marquis de Sade, told me that she suspected that Clinton, like Sade, was only excited by risk and recklessness. In any event, the reality that Clinton never seemed willing to deal with was that his risk was not his alone; that his actions had consequences not just for himself and his family and friends, but also for millions of people, some who believed in him, some who cared about his policies, some who despised his enemies and did not want them to prevail, some who just wanted to think positively about human nature.

TWO

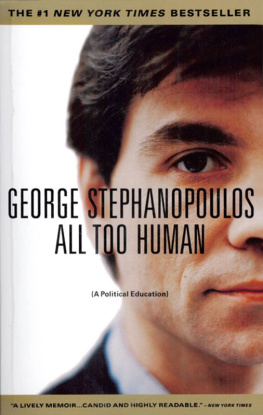

M EMORIES OF OTHER ENCOUNTERS with Clinton came back to me as I waited in the studio for him to deliver his fateful speech. More accurately, they were near encounters. While researching articles for the Post on the forces that shaped his life and career, I had talked with him at length seven times during the 1992 campaign, but starting the day he won the election, the same day that I decided to write his biography, he declined all of my interview requests. I never received a firm no, just indications from one of his White House aides, usually Dee Dee Myers or George Stephanopoulos, sometimes his former chief of staff in Arkansas, Betsey Wright, that he wanted another memo about it, or was still thinking about it, or most likely would not do it but might change his mind later. At one point, I received word through Mrs. Clinton that he was advised not to talk to me by one of his personal lawyers, who said it might detract from his presidential memoirs, a notion I found preposterous.

Next page