By the same author:

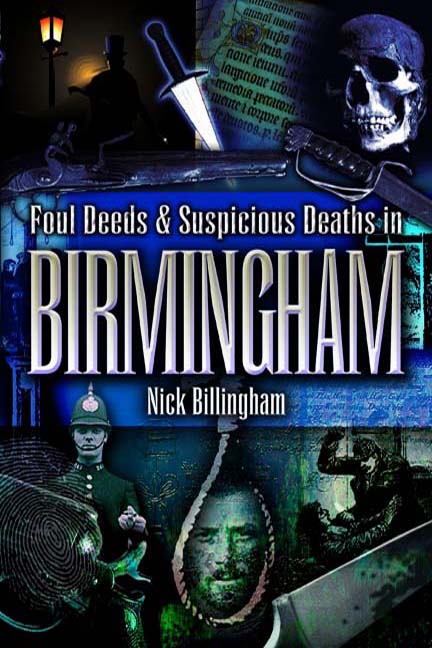

Foul Deeds & Suspicious Deaths in Birmingham

ISBN: 1903425964

Foul Deeds & Suspicious Deaths in Stratford & South Warwickshire

ISBN: 1903425999

Dedication

This book is dedicated to the officers of Birmingham Borough Police

Force who had the unenviable task of sorting these incidents out.

First Published in Great Britain in 2007 by

Wharncliffe Books

an imprint of

Pen and Sword Books Ltd

47 Church Street

Barnsley

South Yorkshire

S70 2AS

Nick Billingham, 2007

ISBN: 978-184563-026-3

eISBN: 978-1-78303-738-4

The right of Nick Billingham to be identified as the author of this work has been asserted by him in accordance with the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act 1988.

A CIP catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library.

All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted, in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording or otherwise, without the prior permission in writing of the publishers.

Typeset in 10/12pt Plantin by Concept, Huddersfield.

Printed and bound in England by Biddies.

Pen and Sword Books Ltd incorporates the imprints of

Pen & Sword Aviation, Pen & Sword Maritime,

Pen & Sword Military, Wharncliffe Books,

Pen & Sword Select, Pen and Sword Military Classics

and Leo Cooper.

For a complete list of Pen & Sword titles please contact

PEN & SWORD BOOKS LIMITED

47 Church Street

Barnsley

South Yorkshire

S70 2BR

England

E-mail: enquiries@pen-and-sword.co.uk

Website: www.pen-and-sword.co.uk

Introduction

T he town of Birmingham stretches a long way back into the mists of time. It traces its roots back to an age where farming was the only activity of any consequence. However, this is not a book of history but of the stories within history; what people got up to. The most dramatic of these were recorded in newspapers and journals, folk memories and the landscape itself. By the eighteenth century, Birmingham was well on the way to becoming a major conurbation, home to engineers and inventors, skilled metal workers and thousands of trades allied to them. Unlike the industrial towns in the North that relied on a single industry like cotton Birmingham maintained a broad range of trades and was thus spared those awful dark satanic mills so typical of the Industrial Revolution.

Murders in the eighteenth century were very rare, although you could be hanged for stealing a sheep or being involved in a riot. Unfortunately, few of these incidents were well recorded and it is not until the nineteenth century that crime reporting became as detailed as a researcher might like. Throughout the nineteenth and into the twentieth century, newspaper reporters brought all the grisly details of a murder to their readers in well-crafted journalism. Sad to say, the introduction of photographs saw a decline in the detail reported. By the Second World War, journalism had shrunk to a few photographs and some salacious headlines. For the most part this unhappy state of affairs has persisted to the present day.

Violence in the eighteenth century was rife, so much so that few ordinary affrays made it into the papers, but every now and then the city exploded into riot. During the 1790s there were several riots caused by the price of food. It was a world still totally dependent on agriculture and a series of bad harvests spelt catastrophe. The price of wheat went up, followed by the price of other grains, until bread was a luxury that few workers could afford. On 29 June 1795, Mr Pickards corn mill and bakery became the focus of a riot, sparked off when he reduced the size of a loaf. Rumours soon swirled round the town that he had secretly buried a hoard of wheat under the mill. A mob of hungry women descended on the mill and started to ransack it. A couple of magistrates then tried to read the Riot Act but had stones thrown at them. The Dragoons and Cavalry were called in and a pitched battle ensued. At one point one of the Dragoons fired indiscriminately into the seething crowd. The bullet passed clean through the chest of a young man called Allen, killing him instantly, and then buried itself into Henry Mason, mortally wounding him. The mob dispersed and two women and a man were arrested as ring leaders. Margaret Bowlker, Mary Mullens and George Hattory were sent to Warwick Gaol to await trial. In the August assizes Margaret was sentenced to death and hanged outside Warwick Gaol. This was just one of many riots caused by the succession of poor harvests at the end of the eighteenth century. An apparently ruthless judiciary maintained the social order of the day, but we must not forget that the mob actions were driven by a fear of starvation and utter poverty.

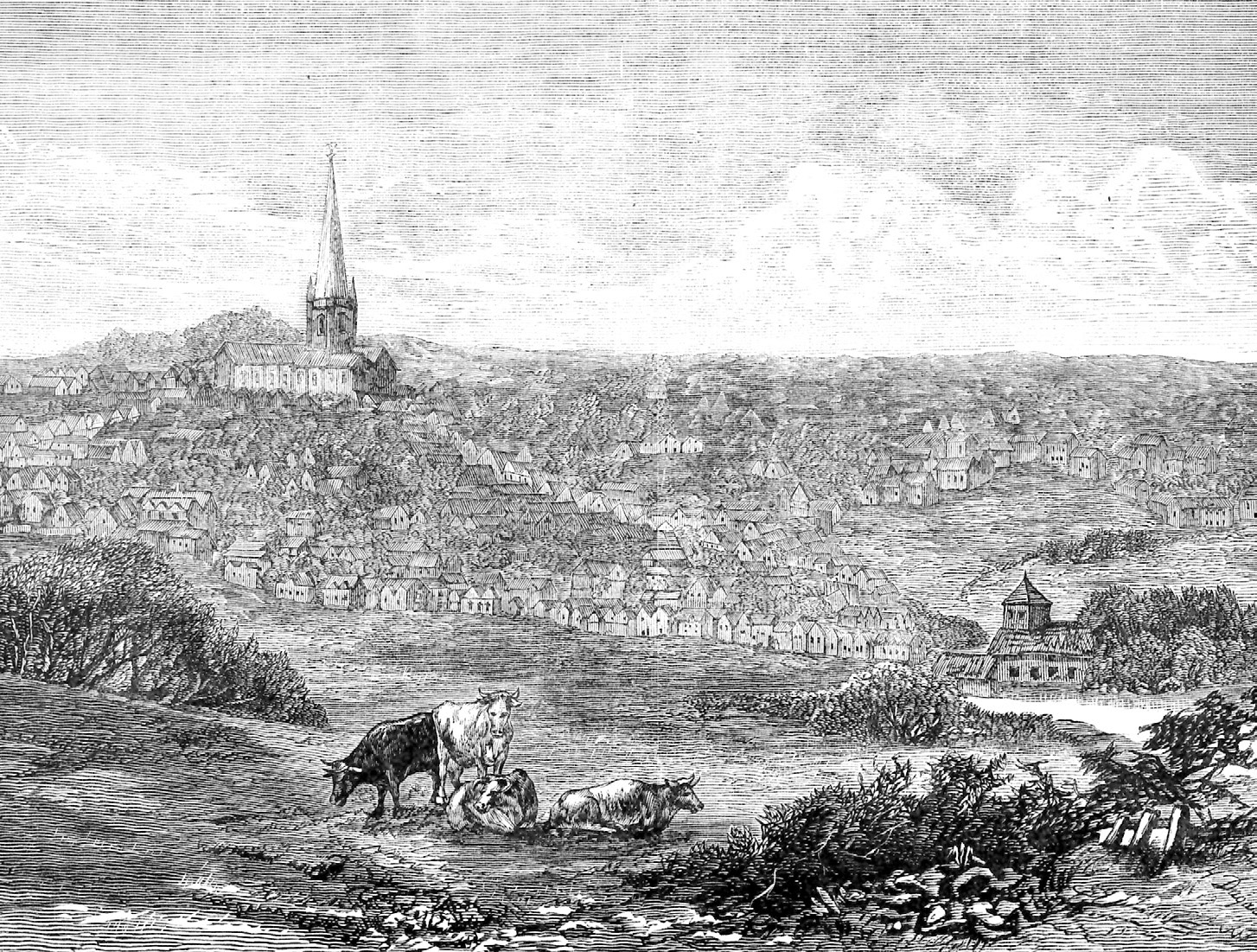

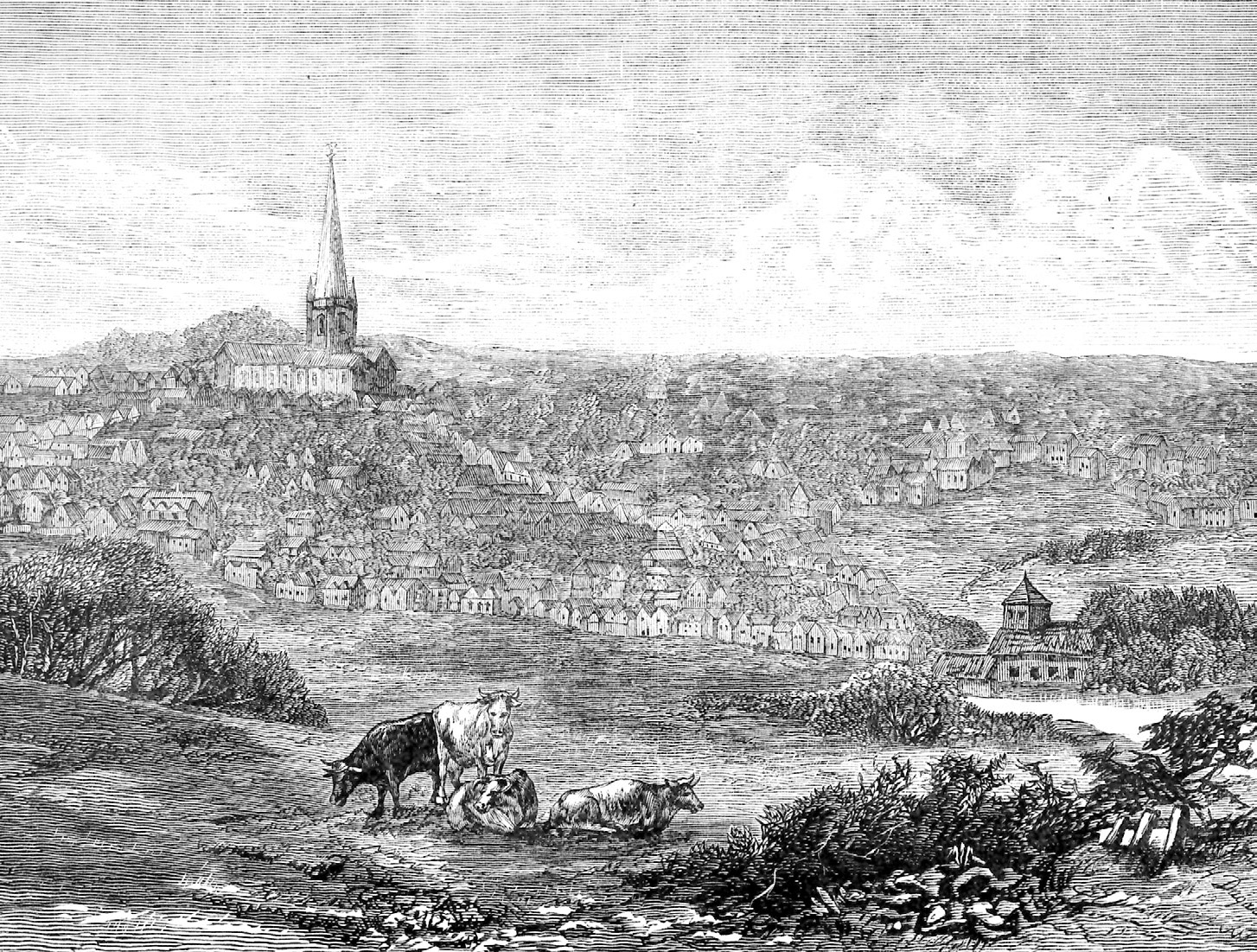

A view of Birmingham in the late eighteenth century. R K Dent

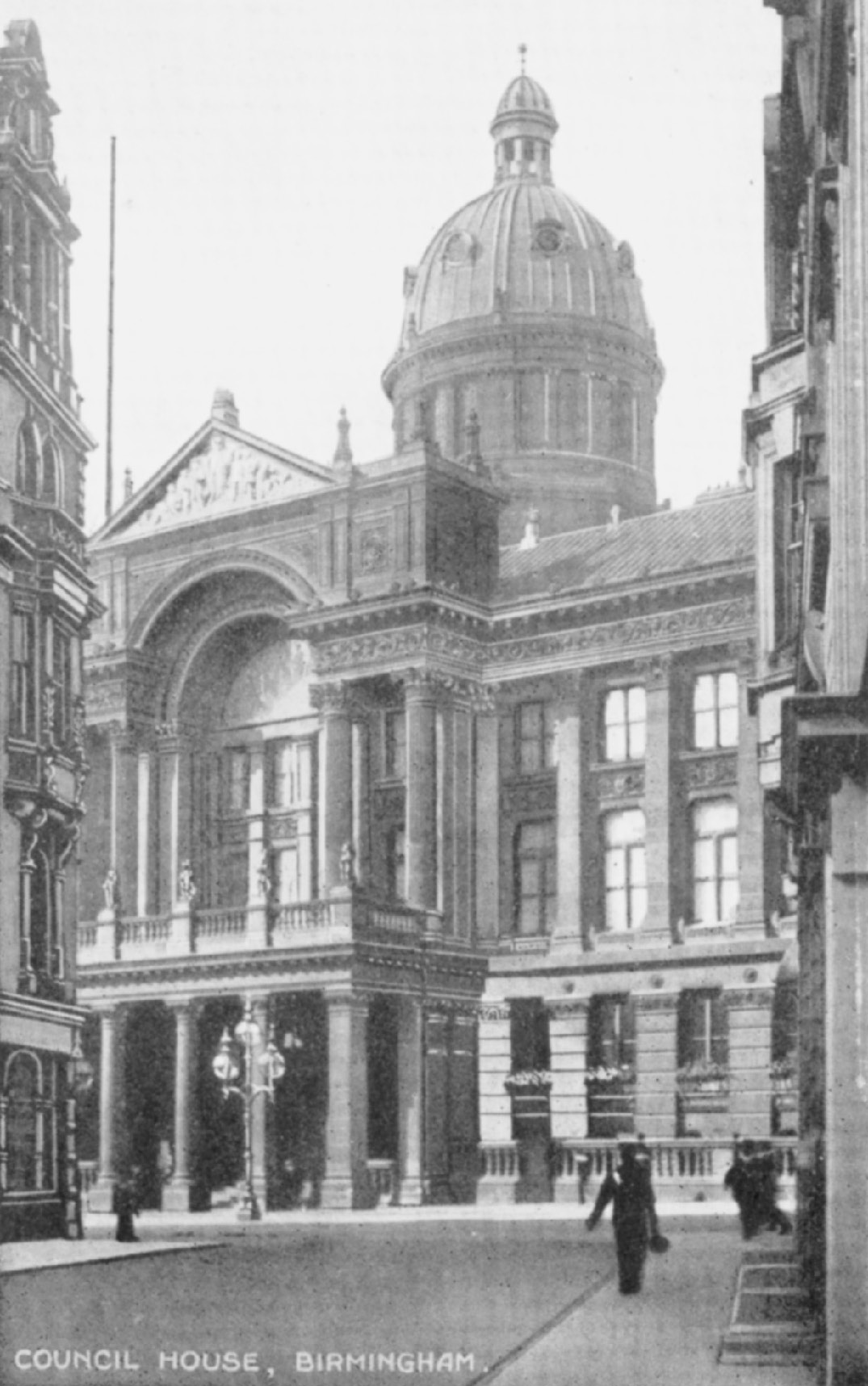

The riches generated by the thousands of trades enabled the Victorians to rebuild the city With real civic pride. Authors collection

In old fashioned days Birmingham Prison was something of a joke. In medieval times offenders were kept in a dungeon of the manor house, but in 1733 a proper prison was built in Peck Lane. It had a couple of dank cells in the cellar and during the riots of 1775 these had to hold 150 people. They were about 8 feet by 5 feet, although during that riot it was standing room only, even upstairs in the gaolers rooms. Things werent quite as organised as today. The gaoler was not paid a salary and so had to earn his money from the prisoners, mostly by brewing beer and selling it to them. The prisoners were only given two chunks of bread and cheese each day, so they bought what they could. Once all their money was gone, the gaoler needed some other customers, so the prison became a part-time pub, punters and prisoners drinking together. The gaoler had to be on his toes to make sure the right people left at closing time. Nothing remains of this rather casual prison now, it lies somewhere underneath New Street Station.

The nineteenth century dawned to a new era of steam engines and coach travel. The town had no official police force but the High Bailiff and magistrates hired constables and watchmen to keep order. On the night of 18 July 1805, one of the constables, Robert Twiford, was patrolling the streets around Snow Hill when a suspicious character he had stopped to question, shot him. Robert took a fair while to die of his injuries, and he managed to give a good description of the villain. Philip Matsell was duly arrested and hauled off to Warwick for trial.

One peculiarity of the era was that murderers were often executed and gibbeted at the scene of the crime. Although Margaret Bowlker had been hung outside Warwick Gaol, Philip Matsell was sentenced to be hung at the site of the shooting, Snow Hill. It created one of the strangest spectacles the town can have ever seen. No one had been executed in Birmingham before. A gibbet and scaffold were built at the bottom of Great Charles Street and on 22 August Matsell was brought in a covered cart from Warwick. At Camp Hill, thousands of people waited to see the condemned man as he was pinioned by the arms and placed in an open cart alongside the hangman and a clergyman. The procession wound its way through Deritend to the scaffold. The scene was astounding, virtually the entire population of the town, 50,000, had turned up, some jeering, some sobbing, others selling trinkets. The throng was so dense that the clergy and guards could barely keep hold of Matsell, let alone even start to read the prayers for the condemned man. It was chaos.

Next page