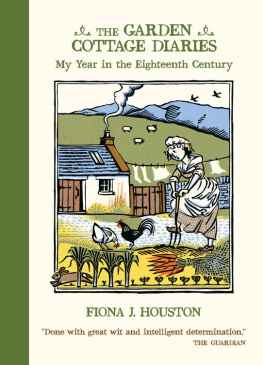

Done with great wit and intelligent determinationA sane response in a relenlessly consuming world FELICITY LAURENCE, THE GUARDIAN

A facinating and colourful scrapbookan object of delightIf ever there was an argument for the survival of the printed book, this is it SALLY MACPHERSON, REFORESTING SCOTLAND JOURNAL [on the hardback edtion]

January 1st, 2005

The wind howled and shrieked, chafing away all night at the cottage. It was unsettling. I was too jumpy to get to sleep. The slates danced on the roof, the chimney roared, and my wool-stuffed mattress felt strange and lumpy. It was like being out at sea, in an unfamiliar berth. I was chilly, but somehow I finally dozed off. When I woke Ive no idea at what time it was to absolute darkness. I am used to darkness, but the cottage windows are tiny. I had closed up the shutters on the field side, but the other window is around a corner. Whatever starlight there may have been between the wind-whipped clouds, it could not filter through to me in my closed box bed.

In time, I learnt how to register the different nuances of grey that denote a cloudy night, a bright night, and the start of dawn. I learnt to slip out of bed in all but total darkness to pee in a bucket. But that night it was a challenge to place my feet on the kist below the box bed and lower myself to the floor. I stumbled to the fire and saw a tiny glow. Feeling that it was beyond me to find the log basket and feed it in the dark, I groped my way back to bed and huddled there, waiting for daylight.

What had brought me to this dark and chilly cottage? It is a story that stretches right back through my life. I dont romanticise the past, but it intrigues me. Since my earliest childhood, with my father and Uncle Arthur, a family friend whose passion for archaeology inspired us all, I have field-walked, looking for evidence of past habitation. I was brought up in Lincolnshire, where Roman roads scored their straight lines across the county and the Anglian people had left their mark, not just in place names but in cemeteries of burial urns, two of which I helped to excavate. This was formative stuff for a seven-year-old. It stirred up my interest in the people who had come before us. I was drawn to the sherds of old pottery that I so readily picked up. Together with the clay pipe stems from our vegetable garden, they formed my earliest collections. These simple domestic things, rather than the kings and queens of A Childs Illustrated History of Britain, fascinated me. I wondered about the daily lives of the people to whom they had belonged. What might life have been like for a native Iron Age woman in Roman Britain, or for the eighteenth-century gardener who had broken his pipe So when I came to Scotland as an adult, it was natural for me to ask questions about the details of the daily lives of ordinary people in the centuries before the Industrial Revolution changed the face of the countryside forever.

To answer my own questions, I have spent years looking at ruined croft houses in the Highlands and sizing up any footings that I could find of the simple turf-and-stone houses that were common in the Lowlands before 1800. I have scoured junk shops for domestic relics. I have read books, studied drawings and paintings that give clues about house interiors (below, late-eighteenth-century scene by Alexander Carse), and I have spent many happy hours in museums.

This all prepared the ground for what I was toying with doing as an experiment. I was becoming more and more attracted to the idea of putting the clock back, and living as people might have done two hundred years ago. All that was needed was some extra impetus to tip me into getting on with it. Then, whilst researching the history of Scottish food for an exhibition in local museums, I read Not on the Label by Felicity Lawrence, food writer for The Guardian. Her shocking revelations about the machinations of supermarkets angered me so much that I started to relay them to anyone who would listen. Whatever they may tell their customers, supermarkets sole interest is in selling products in order to give a good return to their shareholders. They do not care about the nutritional value of their food, about the environmental impact of their operation, or, most especially, about the survival of the poor people who actually farm the crops that end up, in one form or another, on supermarket shelves. Their whole operation is ethically suspect, the greenwash handed out by their publicity departments.

My rant had gone on. It probably wasnt the first time that I had ranted, either. I was so focused on the unwholesomeness of lots of so-called food products: crisps, confectionary, sweet drinks, ready-made meals, that I was in danger of becoming a bore. I declared that people in Scotland were better fed at the end of the eighteenth century than they are now. Someone called my bluff. You try living as they did in the eighteenth century! he said.

So I decided I would.

Moreover, I decided to live that way for a whole calendar year. I did not want to dabble. I wanted to experience the realities of all seasons with their pleasures and hardships, to cut off from the industrialized world for a significant stretch of time.

I had other motives, of course. By doing something so unusual, I knew that I had a good chance of having my story published in a newspaper. I saw this as being central to my endeavour. My pitch worked. I was given a monthly page in The Herald, originally the daily read for the west of Scotland, but increasingly for the entire country. I needed that audience because it would keep up my resolve. I also anticipated there being a good deal to say, not least because, in looking back to the simple life of the past, I had one eye on the future.

We none of us know what the next decades hold for us. The evidence is gathering fast that global warming is becoming a reality that will affect us here directly, and all too soon. Our weather is becoming more unpredictable and violent. In many more distant parts of the world, land is now liable to catastrophic flooding, or else is burning up and turning into deserts where no crops can be grown. Suddenly, life as we know it seems to be very much more precarious than before. Some authorities suggest that the whole biosphere is at risk; others foretell consequences that are almost as dire.